Summary

Who we spend time with evolves across our lifetimes. In adolescence we spend the most time with our parents, siblings, and friends; as we enter adulthood we spend more time with our co-workers, partners, and children; and in our later years we spend an increasing amount of time alone. But this doesn’t necessarily mean we are lonely; rather, it helps reveal the complex nature of social connections and their impact on our well-being.

As we go through life we build personal relationships with different people – family, friends, coworkers, partners. These relationships, which are deeply important to all of us, evolve with time. As we grow older we build new relationships while others transform or fade, and towards the end of life many of us spend a lot of time alone.

Taking the big picture over the entire life course: Who do we actually spend our time with?

To understand how social connections evolve throughout our lives we can look at survey data on how much time people spend with others, and who that time is spent with.

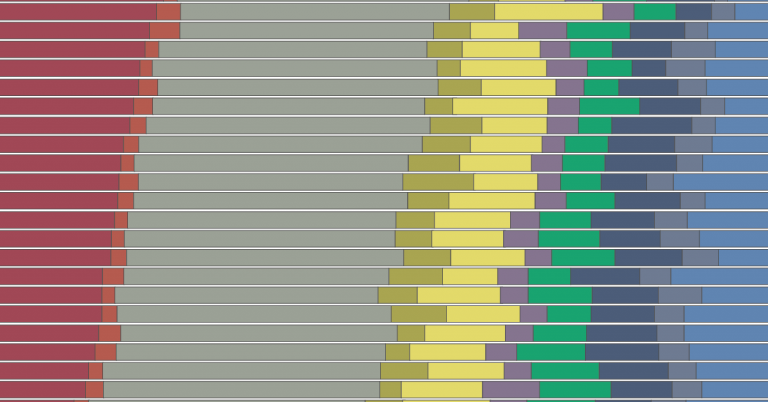

The chart here shows the amount of time that people in the US report spending in the company of others, based on their age. The data comes from time-use surveys, where people are asked to list all the activities that they perform over a full day, and the people who were there during each activity. We currently only have data with this granularity for the US – time-use surveys are common across many countries, but what is special about the US is that respondents of the American Time Use Survey are asked to list everyone who was present for each activity.

The numbers in this chart are based on averages for a cross-section of the American society – people are only interviewed once, but we have brought together a decade of surveys, tabulating the average amount of time that survey respondents of different ages report spending with other people.1

Who we spend our time with changes a lot over the course of life

When we’re young – particularly in our teens – we spend a lot of our time with friends, parents, siblings and extended family. As we enter our 20s, time with friends, siblings and parents starts to drop off quickly. Instead, we start spending an increasing amount of time with partners and children. (The chart shows an average across Americans, so for those that have children the time spent with children is even higher, since the average is pulled down by those without children.)

As the chart shows, this continues throughout our 30s, 40s and 50s – over this period of their life, Americans spend much of their time with partners, children and, unsurprisingly, co-workers.

For those 60 and older, we see a significant drop-off in time spent with co-workers. This makes sense, considering many people in the US enter retirement in their mid 60s. We see that this time is partly displaced by more time with partners.

In terms of the diversity of interactions, this chart suggests that the number of people with whom we interact is highest around 40, but then things change substantially after that. And this is perhaps the most conspicuous trend in the chart: above 40, people spend an increasing amount of time alone.

Older people spend a large amount of time alone and it is understandable why – time spent alone increases with age because this is when health typically deteriorates and people lose relatives and friends.

Indeed, many people who are older than 60 live alone as this chart shows clearly: living alone is particularly common for older adults. Today nearly 4 out of every 10 Americans who are older than 89 years old live alone.

Another interesting point here is that the share of people across all age groups who live alone has been increasing over time. This is part of a more general global trend – if you want to read more about the global ‘rise of living alone’, we provide a detailed account of this trend across countries in a companion post.

The data shows that as we become older we tend to spend more and more time alone. What’s more, the data also shows that older people today spend more time alone than older people did in the past.

We might think older people are therefore more lonely – but this is not necessarily the case.

Spending time alone is not the same as feeling lonely. This is a point that is well recognised by researchers, and one which has been confirmed empirically across countries. Surveys that ask people about living arrangements, time use, and feelings of loneliness find that solitude, by itself, is not a good predictor of loneliness. You can read our overview of the evidence in this post.

So, what about loneliness? If we focus on self-reported loneliness, there is little evidence of an upward trend over time in the US; and importantly, it’s not the case that loneliness keeps going up as we become older. In fact a recent study based on surveys that track the same individuals over time found that after age 50 – which is the earliest age of participants in the analysis – loneliness tended to decrease, until about 75, after which it began to increase again.

Taking the evidence together, the message is not that we should be sad about the prospect of aging, but rather that we should recognise the fact that social connections are complex. We often tend to look at the amount of time spent with others as a marker of social well-being; but the quality of time spent with others, and our expectations, matter even more for our feelings of connection and loneliness.