There is a popular perception that countries in Northern Europe are heavily individualistic and because of this people in these societies tend to be much lonelier. The data, however, does not support this claim.

What is true is that in countries such as Denmark and Switzerland, it is very common for people to live alone. But contrary to what many believe, this does not translate into higher levels of self-reported loneliness.

Below we discuss the data in more detail, and show that this can be partly explained by the fact that loneliness and aloneness are just not the same. Both loneliness and solitude deserve attention, but it’s important not to conflate them.

Loneliness describes a subjective feeling; this is conceptually distinct from objective physical isolation.

In the chart here we show estimates on self-reported feelings of loneliness among older adults. The data comes from various surveys asking people directly whether they often experience feelings of loneliness (e.g. “I have no-one with whom I can discuss important matters with”).

The differences in the prevalence of loneliness across countries are very large. At the bottom of the list, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden and the US all have rates below 30%, while at the top of the list Greece, Israel and Italy all have rates of close to or above 50%.

The data is available only for fifteen countries, but this sample does not suggest that ‘rich individualistic societies’ are lonelier than others. In fact, at the very bottom are two countries in which the share of people living alone is among the highest in the world.

Similar to loneliness, we can measure perceptions of social support by asking people directly. This is what the polling organization Gallup did in their flagship World Poll survey. Specifically, they asked: “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?”

The chart here presents the results from this survey, plotting the share of people who responded “yes” to this question.1

Differences across countries are not very large. The lowest and highest average levels of support corresponds to Mexico and Iceland, at 80% and 98% respectively.

The second point that stands out is that, again, there’s no support for the claim that richer countries that are considered to be more individualistic (e.g. North European countries) have lower levels of family and friendship support.

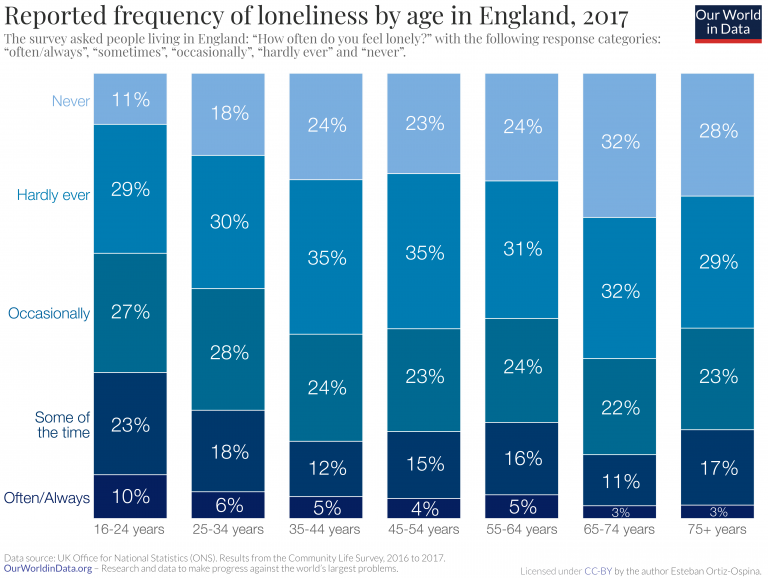

Are people who live alone more likely to say they feel lonely?

The researchers Caitlin Coyle and Elizabeth Dugan explored this question using data from the Health and Retirement Study in the US. In their analysis, covering almost 12,000 respondents over the years 2006-2008, they found that loneliness and social isolation are not highly correlated at the individual level.2

To be precise, Coyle and Dugan found a correlation coefficient of 0.2. That means the correlation is positive, and it is statistically larger than zero; but it’s not very large in absolute terms. Their study does not provide the raw data, but in general, a scatter plot with correlation 0.2 is pretty much just a cloud of dots.

This means you cannot predict much of the variability in loneliness from observed differences in living arrangements. Some people who live alone are lonely, but many are not. Concluding that someone who lives alone must feel lonely is very often wrong.3

People do not seem to be more lonely in societies that are traditionally labeled as ‘individualistic’.

What is true is that in these societies it is particularly common for people to live alone. But being alone and feeling lonely don’t always go hand in hand. Many people feel lonely even if they are not physically isolated; and many people who are physically isolated do not feel lonely.

The aggregate statistics confirm this. Surveys that ask people about living arrangements, time use, and feelings of loneliness, find that solitude, by itself, does not predict feelings of loneliness.

The fact that people in individualistic countries are not more likely to feel lonely may of course capture differences in expectations regarding social relations. But to the extent that loneliness is a subjective experience, these cross-country differences are still important to understand well-being.

Both loneliness and solitude deserve attention, but it’s important not to conflate them.

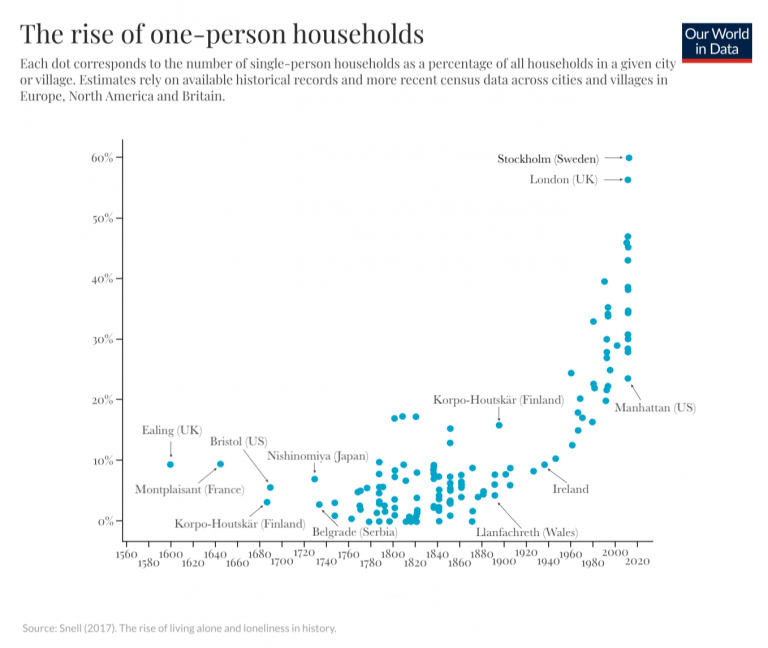

The difference between loneliness and solitude can help explain why there’s no evidence of rising loneliness over time, even in countries where solitary living arrangements are becoming increasingly common. In Our World in Data you can read more about trends in loneliness, as well as trends in living arrangements, here: