In the US, the share of adults who live alone nearly doubled over the last 50 years. This is not only happening in the US: single-person households have become increasingly common in many countries across the world, from Angola to Japan.

Historical records show that this ‘rise of living alone’ started in early-industrialized countries over a century ago, accelerating around 1950. In countries such as Norway and Sweden, single-person households were rare a century ago, but today they account for nearly half of all households. In some cities they are already the majority.

Surveys and census data from recent decades show that people are more likely to live alone in rich countries, and the prevalence of single-person households is unprecedented historically.

Social connections – including contact with friends and family – are important for our health and emotional well-being. Hence, as single-person households become more common, there will be new challenges to connect and provide support to those living alone, particularly in poorer countries where welfare states are weaker.

But it’s important to keep things in perspective. It’s unhelpful to compare the rise of living alone with a ‘loneliness epidemic’, which is what newspaper articles often write in alarming headlines.

Loneliness and solitude are not the same, and the evidence suggests that self-reported loneliness has not been growing in recent decades.

Historical records of inhabitants across villages and cities in today’s rich countries give us insights into how uncommon it was for people to live alone in the past.

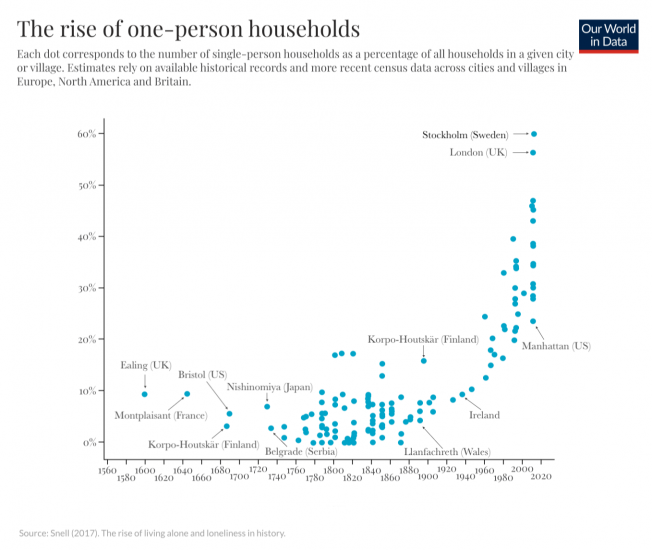

The chart here, adapted from a paper by the historian Keith Snell, shows estimates of the share of single-person households across different places and times, using a selection of the available historical records and more recent census data. Each dot corresponds to an estimate for one settlement in Europe, North America, Japan or Britain.1

The share of one-person households remained fairly steady between the early modern period and through the 19th century – typically below 10%. Then growth started in the twentieth century, accelerating in the 1960s.

The current prevalence of one-person households is unprecedented historically. The highest point recorded in this chart corresponds to Stockholm, in 2012, where 60% of households consist of one person.

For recent decades, census data can be combined with data from large cross-country surveys, to provide a global perspective on the proportion of households with only one member (i.e. the proportion of single-person households). This gives us a proxy for the prevalence of solitary living arrangements.2

We produced this chart combining individual reports from statistical country offices, cross-country surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys, and estimates published in the EU’s Eurostat, the UN’s Demographic Year Books, and the Deutschland in Daten dataset.

The chart shows that the trend of rising single-person households extends across all world regions. There are large differences between countries – from more than 40% in northern European countries to 1% in low-income Asian countries.

(NB. For the US and Canada there are long-run time series from census data that let us directly track the share of people who live alone. This is shown in this other chart, where you can see the same trend.)

National income per capita and the share of one-person households are strongly correlated: As the chart here shows, people are more likely to live alone in rich countries.

In this interactive chart you can move the slider to see changes over time. This reveals that the rise of single-person households tends to be larger in countries where GDP per capita has grown more. (NB. You can also see the correlation over time in this other scatter plot comparing average growth in GDP vs average growth in one-person households).

These correlations are partly due to the fact that people who can afford to, often choose to live alone. Indeed, rising incomes in many countries are likely part of the reason why people are more likely to live alone today than in the past.

But there must be more to it since even at the same level of incomes there are clear differences between regions. In particular, Asian countries have systematically fewer one-person households than African countries with comparable GDP levels. Ghana and Pakistan, for example, have similar GDP per capita, but in Pakistan one-person households are extremely rare, while in Ghana they are common (about 1 in 4). This suggests culture and country-specific factors also play an important role.

Additionally, there are other non-cultural country-specific factors that are likely to play a role. In particular, rich countries often have more extensive social support networks, so people in these countries find it easier to take risks. Living alone is more risky in poorer countries, because there’s often less supply of services and infrastructure to support more solitary living arrangements.

And finally, it’s also likely that some of the causality runs in the opposite direction. It’s not only that incomes, culture or welfare states enable people to live alone, but also that for many workers attaining higher incomes in today’s economy often demands changes in living arrangements. Migration from rural to urban areas is the prime example.

Social connections – including contact with friends and family – are important for our health and emotional well-being. Hence, as the ‘rise of living alone’ continues, there will be new challenges to connect people and provide support to those living alone, particularly in poorer countries where communication technologies are less developed and welfare states are weaker.

But, it’s also important to keep in mind that living alone is not the same as feeling lonely. There’s evidence that living alone is, by itself, a poor predictor of loneliness. Self-reported loneliness has not been growing in recent decades, and in fact, the countries where people are most likely to say they have support from family and friends, are the same countries – in Scandinavia – where a large fraction of the population lives alone.

Incomes and freedom of choice are not the only drivers of the ‘rise of living alone’; but it would be remiss to ignore they do contribute to this trend.

Higher incomes, economic transitions that enable migration from agriculture in rural areas into manufacturing and services in cities, and rising female participation in labor markets all play a role. People are more likely to live alone today than in the past partly because they are increasingly able to do so.