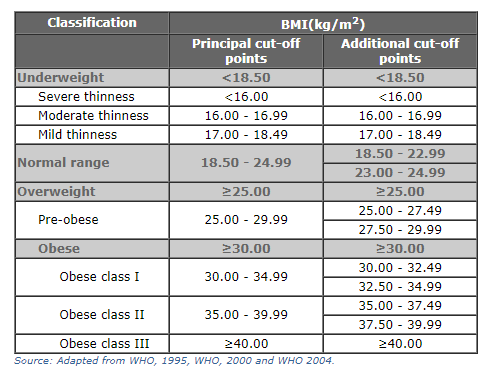

Obesity is most commonly measured using the body mass index (BMI) scale. The World Health Organization define BMI as: “a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify underweight, overweight and obesity in adults.”1

BMI values are used to define whether an individual is considered to be underweight, healthy, overweight or obese. The WHO defines these categories using the cut-off points: an individual with a BMI between 25.0 and 30.0 is considered to be ‘overweight’; a BMI greater than 30.0 is defined as ‘obese’.2

Summary

- Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for premature death. It was linked to 4.7 million deaths globally in 2017.

- 8% of global deaths were attributed to obesity in 2017.

- There are large differences – 10-fold – in death rates from obesity across the world.

- 13% of adults in the world are obese.

- 39% of adults in the world are overweight.

- One-in-five children and adolescents, globally, are overweight.

- Obesity is determined by the balance of energy intake and expenditure. Rates have increased as the calories have become more readily available.

Related research entries

Food per person – food availability has increased significantly in most countries across the world. How does the supply of calories, protein and fats vary between countries? How has this changed over time?

Hunger and Undernourishment – obesity rates have now overtaken hunger rates globally. But it remains the case that high levels of obesity and hunger can occur in a country at any given time. How does undernourishment vary across the world? How has it changed over time?

Micronutrient Deficiency – getting sufficient intake of calories (a requirement for obesity) does not guarantee an individual gets the full range of essential vitamins and minerals (micronutrients) for good health. Dietary diversity varies significantly across the world. How common is micronutrient deficiency and who is most at risk?

Obesity is one of the world’s largest health problems – one that has shifted from being a problem in rich countries, to one that spans all income levels.

The Global Burden of Disease is a major global study on the causes and risk factors for death and disease published in the medical journal The Lancet.3 These estimates of the annual number of deaths attributed to a wide range of risk factors are shown here. This chart is shown for the global total, but can be explored for any country or region using the “change country” toggle.

Obesity – defined as having a high body-mass index – is a risk factor for several of the world’s leading causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes and various types of cancer.4 Obesity does not directly cause of any of these health impacts but can increase their likelihood of occurring. In the chart we see that it is one of the leading risk factors for death globally.

According to the Global Burden of Disease study 4.7 million people died prematurely in 2017 as a result of obesity. To put this into context: this was close to four times the number that died in road accidents, and close to five times the number that died from HIV/AIDS in 2017.5

Globally, 8% of deaths in 2017 were the result of obesity – this represents an increase from 4.5% in 1990.

This share varies significantly across the world. In the map here we see the share of deaths attributed to obesity across countries.

Across many middle-income countries – particularly across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Africa, and Latin America – more than 15% of deaths were attributed to obesity in 2017. This most likely results from having a high prevalence of obesity, but poorer overall health and healthcare systems relatively to high-income countries with similarly high levels of obesity.

In most high-income countries this share is in the range of 8 to 10%. This is about half the share of many middle-income countries. The large outliers among rich countries are Japan and South Korea: there only around 5% of premature deaths are attributed to obesity.

Across low-income countries – especially across Sub-Saharan Africa – obesity accounts for less than 5% of deaths.

Death rates from obesity give us an accurate comparison of differences in its mortality impacts between countries and over time. In contrast to the share of deaths that we studied before, death rates are not influenced by how other causes or risk factors for death are changing.

In the map here we see differences in death rates from obesity across the world. Globally, the death rate from obesity was around 60 per 100,000 in 2017.

The overall picture does in fact match closely with the share of deaths: death rates are high across middle-income countries, especially across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Africa and Latin America. Rates there can be close to 200 per 100,000. This is more than ten times greater than rates at the bottom: Japan and South Korea have the lowest rates in the world at 14 and 20 deaths per 100,000, respectively.

When we look at the relationship between death rates and the prevalence of obesity we find a positive one: death rates tend to be higher in countries where more people have obesity. But what we also notice is that for a given prevalence of obesity, death rates can vary by a factor of four. 23% of Russian and Norwegian are obese, yet Russia’s death rate is four times higher. Clearly it’s not only the prevalence of obesity that plays a role but also other factors such as underlying health, other confounding risk factors (such as alcohol, drugs, smoking and other lifestyle factors) and healthcare systems.

Globally, 13% of adults aged 18 years and older were obese in 2016.6 Obesity is defined as having a body-mass index equal to or greater than 30.

In the map here we see the share of adults who are obese across countries. Overall we see a pattern roughly in line with prosperity: the prevalence of obesity tends to be higher in richer countries across Europe, North America, and Oceania. Obesity rates are much lower across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

More than one-in-three (36%) of adults in the United States were obese in 2016. In India this share was around 10 times lower (3.9%).

The relationship between income and obesity generally holds true – as we see in the comparison here. But there are some notable exceptions. The small Pacific Island States stand out clearly: they have very high rates of obesity – 61% in Nauru and 55% in Palau – for their level of income. At the other end of the spectrum, Japan, South Korea and Singapore have very low levels of obesity for their level of income.

Related charts – share of men and women that are obese. This map allows you to explore the share of men that are obese; this map allows you to explore this data for women across the world. This chart shows the comparison of obesity in men and women.

Globally, 39% of adults aged 18 years and older were overweight or obese in 2016.7 Being overweight is also defined based on body-mass index: the threshold value is lower than for obesity, with a BMI equal to or greater than 25.

In the map here we see the share of adults who are overweight or obese across countries. The overall pattern is very closely aligned with the distribution of obesity across the world: the share of people who are overweight tends to be higher in richer countries and lower at lower incomes. What is of course true is that the share who are overweight (have a BMI greater than or equal to 25) is much higher than the share that are obese (a BMI of 30 or greater).

In most high-income countries, around two-thirds of adults are overweight or obese. In the US, 70% are. At the lowest end of the scale, across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa around 1-in-5 adults have a BMI greater than 25.

Related charts – share of men and women that are overweight or obese. This map allows you to explore the share of men that are overweight or obese; this map allows you to explore this data for women across the world.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is used to define the share of individuals that are underweight, in the ‘healthy’ range, overweight and obese.

In the map here we see the distribution of mean BMI for adult women – aged 18 years and older – across the world. The global mean BMI for women in 2016 was 25 – just on the threshold from the WHO’s ‘healthy’ to ‘overweight’ classification. This has increased from a mean BMI of 22 – in the mid-range of ‘healthy’ – in the 1970s.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is used to define the share of individuals that are underweight, in the ‘healthy’ range, overweight and obese.

In the map here we see the distribution of mean BMI for adult men – aged 18 years and older – across the world. The global mean BMI for men in 2016 was 24.5 – just on the threshold from the WHO’s ‘healthy’ to ‘overweight’ classification. This has increased from a mean BMI of 21.7 – in the mid-range of ‘healthy’ – in the 1970s.

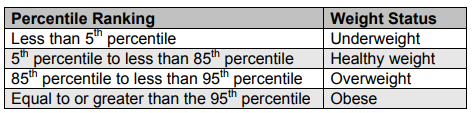

Obesity and overweight in children are also measured on the basis of body-mass-index (BMI). However, interpretation of BMI scores is treated differently for children and adolescents. Weight categories are defined in relation to WHO Growth Standards – a child is defined as overweight if their weight-for-height is more than two standard deviations from the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards.

The World Health Organization reports that the share of children and adolescents aged 5-19 who are overweight or obese has risen from 4% in 1975 to around 18% in 2016.8

In the map here we see the share of very young children – aged 2 to 4 years old – who are overweight based on WHO Child Growth Standards. In many countries as many as every third or fourth child is overweight.

At a basic level, weight gain – eventually leading to being overweight or obesity – is determined by a balance of energy.9 When we consume more energy – typically measured in kilocalories – than the energy expended to maintain life and carry out daily activites, we gain weight. This is a called an energy surplus. When we consume less energy than we expend, we lose weight – this is an energy deficit.

This means there are two potential drivers of the increase in obesity rates in recent decades: either an increase in kilocalorie intake i.e. we eat more; or we expend less energy in daily life through lower activity levels. Both elements are likely to play a role in the rise in obesity.

To tackle obesity it’s likely that interventions which address both components: energy intake and expenditure are necessary.10

Over the past century – but particularly over the past 50 years – the supply of calories has increased across the world. In the 1960s, the global average supply of calories (that is, the availability of calories for consumers to eat) was 2200kcal per person per day. By 2013 this had increased to 2800kcal.

Across most countries, energy consumption has therefore increased. If this increase was not met with an increase in energy expenditure, weight gain and a rise in obesity rates is the result.

In the chart here we see the relationship between the share of men that are overweight or obese (on the y-axis) versus the daily average supply of kilocalories per person. Overall we see a strong positive relationship: countries with higher rates of overweight tend to have a higher supply of calories.

If you press ‘play’ on the interactive timeline you can see how this has changed for each country over time. Most countries move upwards and to the right: the supply of calories has increased at the same time as obesity rates have increased.

The most common metric used for assessing the prevalence of obesity is the body mass index (BMI) scale. The World Health Organization define BMI as: “a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify underweight, overweight and obesity in adults. It is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2). For example, an adult who weighs 70kg and whose height is 1.75m will have a BMI of 22.9.”11

Measured BMI values are used to define whether an individual is considered to be underweight, healthy, overweight or obese. The WHO defines these categories using the cut-off points in the table. For example, an individual with a BMI between 25.0 and 30.0 is considered to be ‘overweight’; a BMI greater than 30.0 is defined as ‘obese’.12

The metric for measuring bodyweight in children and adolescents is also the body mass index (BMI) scale, measured in the same way described above. However, interpretation of BMI scores is treated differently for children and adolescents. Whilst there is no differentiation of weight categories in adults based on sex or age, these are important factors in the body composition of children. Factors such as age, gender and sexual maturation affect the BMI of younger individuals. For interpretation of individuals between the ages of 2 and 20 years old, BMI is measured relative to peers of the same age and gender, with weight classifications judged as shown in the table.13

The merits of using BMI as an indicator of body fat and obesity are still contested. A key contention to the use of BMI indicators is that it provides a measure of body mass/weight rather than providing a direct measure of body fat. Whilst physicians continue to use BMI as a general indicator of weight-related health risks, there are some cases where its use should be considered more carefully14:

- muscle mass can increase bodyweight; this means athletes or individuals with a high muscle mass percentage can be deemed overweight on the BMI scale, even if they have a low or healthy body fat percentage;

- muscle and bone density tends to decline as we get older; this means that an older individual may have a higher percentage body fat than a younger individual with the same BMI;

- women tend to have a higher body fat percentage than men for a given BMI.

Physicians must therefore evaluate BMI results carefully on a individual basis. Despite outlier cases where BMI is an inappropriate indicator of body fat, its use provides a reasonable measure of the risk of weight-related health factors across most individuals across the general population.

- Data: Mean and distributions of body mass index (BMI), by country

- Geographical coverage: Global- by country

- Time span: 1975 onwards

- Available at: http://www.ncdrisc.org/index.html

- Data: Share of population by weight category

- Geographical coverage: Global – by country

- Time span: 1960 onwards

- Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/body-mass-index

- Data: Number of deaths and death rates from obesity

- Geographical coverage: Global – by country

- Time span: 1990 onwards

- Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/results/data-visualizations