Technology can change the world in ways that are unimaginable, until they happen. Switching on an electric light would have been unimaginable for our medieval ancestors. In their childhood, our grandparents would have struggled to imagine a world connected by smartphones and the Internet.

Similarly, it is hard for us to imagine the arrival of all those technologies that will fundamentally change the world we are used to.

We can remind ourselves that our own future might look very different from the world today by looking back at how rapidly technology has changed our world in the past. That’s what this article is about.

One insight I take away from this long-term perspective is how unusual our time is. Technological change was extremely slow in the past – the technologies that our ancestors got used to in their childhood were still central to their lives in their old age. In stark contrast to those days, we live in a time of extraordinarily fast technological change. For recent generations, it was common for technologies that were unimaginable in their youth to become common later in life.

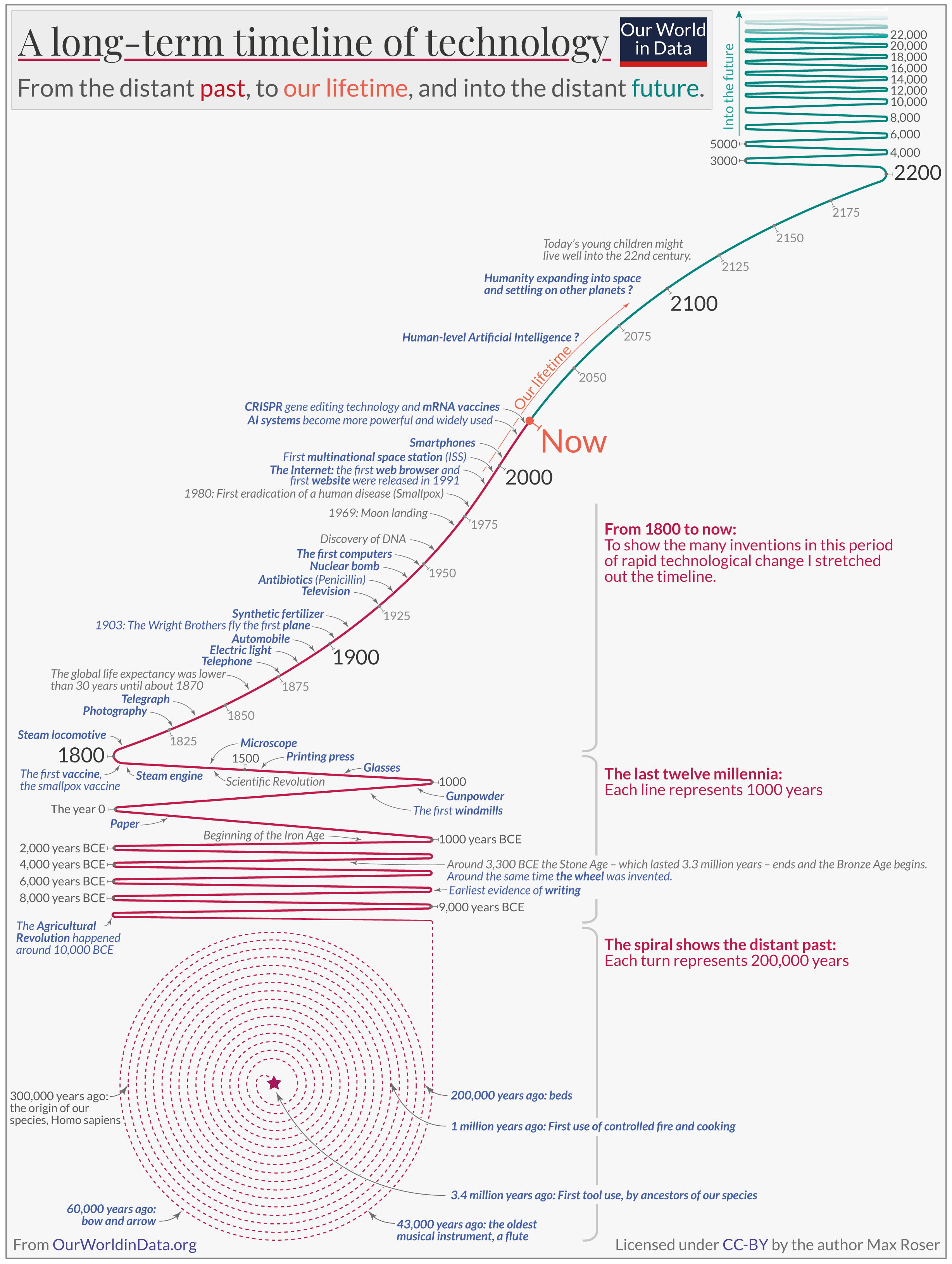

The big visualization offers a long-term perspective on the history of technology.1

The timeline begins at the center of the spiral. The first use of stone tools, 3.4 million years ago, marks the beginning of this history of technology.2 Each turn of the spiral then represents 200,000 years of history. It took 2.4 million years – 12 turns of the spiral – for our ancestors to control fire and use it for cooking.3

To be able to visualize the inventions in the more recent past – the last 12,000 years – I had to unroll the spiral. I needed more space to be able to show when agriculture, writing, and the wheel were invented. During this period, technological change was faster, but it was still relatively slow: several thousand years passed between each of these three inventions.

From 1800 onwards, I stretched out the timeline even further to show the many major inventions that rapidly followed one after the other.

The long-term perspective that this chart provides makes it clear just how unusually fast technological change is in our time.

You can use this visualization to see how technology developed in particular domains. Follow, for example, the history of communication: from writing, to paper, to the printing press, to the telegraph, the telephone, the radio, all the way to the Internet and smartphones.

Or follow the rapid development of human flight. In 1903, the Wright brothers took the first flight in human history (they were in the air for less than a minute), and just 66 years later, we landed on the moon. Many people saw both within their lifetimes: the first plane and the moon landing.

This large visualization also highlights the wide range of technology’s impact on our lives. It includes extraordinarily beneficial innovations, such as the vaccine that allowed humanity to eradicate smallpox, and it includes terrible innovations, like the nuclear bombs that endanger the lives of all of us.

What will the next decades bring?

The red timeline reaches up to the present and then continues in green into the future. Many children born today, even without any further increases in life expectancy, will live well into the 22nd century.

New vaccines, progress in clean, low-carbon energy, better cancer treatments – a range of future innovations could very much improve our living conditions and the environment around us. But, as I argue in a series of articles, there is one technology that could even more profoundly change our world: artificial intelligence (AI).

One reason why artificial intelligence is such an important innovation is that intelligence is the main driver of innovation itself. This fast-paced technological change could speed up even more if it’s not only driven by humanity’s intelligence, but artificial intelligence too. If this happens, the change that is currently stretched out over the course of decades might happen within very brief time spans of just a year. Possibly even faster.4

I think AI technology could have a fundamentally transformative impact on our world. In many ways, it is already changing our world, as I documented in this companion article. As this technology is becoming more capable in the years and decades to come, it can give immense power to those who control it (and it poses the risk that it could escape our control entirely).

Such systems might seem hard to imagine today, but AI technology is advancing very fast. Many AI experts believe there is a real chance that human-level artificial intelligence will be developed within the next decades, as I documented in this article.

Technology will continue to change the world – we should all make sure that it changes it for the better

What is familiar to us today – photography, the radio, antibiotics, the Internet, or the International Space Station circling our planet – was unimaginable to our ancestors just a few generations ago. If your great-great-great grandparents could spend a week with you they would be blown away by your everyday life.

What I take away from this history is that I will likely see technologies in my lifetime that appear unimaginable to me today.

In addition to this trend towards increasingly rapid innovation, there is a second long-run trend. Technology has become increasingly powerful. While our ancestors wielded stone tools, we are building globe-spanning AI systems and technologies that can edit our genes.

Because of the immense power that technology gives those who control it, there is little that is as important as the question of which technologies get developed during our lifetimes. Therefore I think it is a mistake to leave the question about the future of technology to the technologists. Which technologies are controlled by whom is one of the most important political questions of our time, because of the enormous power that these technologies convey to those who control them.

We all should strive to gain the knowledge we need to contribute to an intelligent debate about the world we want to live in. To a large part this means gaining the knowledge, and wisdom, on the question of which technologies we want.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my colleagues Hannah Ritchie, Bastian Herre, Natasha Ahuja, Edouard Mathieu, Daniel Bachler, Charlie Giattino, and Pablo Rosado for their helpful comments to drafts of this essay and the visualization. Thanks also to Lizka Vaintrob and Ben Clifford for a conversation that initiated this visualization.