The shockwave and heat that the detonation of a single nuclear weapon creates can end the lives of millions of people immediately.

But even larger is the devastation that would follow a nuclear war.

The first reason for this is nuclear fallout. Radioactive dust from the detonating bombs rises up into the atmosphere and spreads out over large areas of the world from where it falls down and causes deadly levels of radiation.

The second reason is less widely known. But this consequence – ‘nuclear winter’ and the worldwide famine that would follow – is now believed to be the most serious consequence of nuclear war.

Cities that are attacked by nuclear missiles burn at such an intensity that they create their own wind system, a firestorm: hot air above the burning city ascends and is replaced by air that rushes in from all directions. The storm-force winds fan the flames and create immense heat.

From this firestorm large columns of smoke and soot rise up above the burning cities and travel all the way up to the stratosphere. There it spreads around the planet and blocks the sun’s light. At that great height – far above the clouds – it cannot be rained out, meaning that it will remain there for years, darkening the sky and thereby drying and chilling the planet.

The nuclear winter that would follow a large-scale nuclear war is expected to lead to temperature declines of 20 or even 30 degrees Celsius (60–86° F) in many of the world’s agricultural regions – including much of Eurasia and North America. Nuclear winter would cause a ‘nuclear famine’. The world’s food production would fail and billions of people would starve.1

These consequences – nuclear fallout and nuclear winter leading to famine – mean that the destruction caused by nuclear weapons is not contained to the battlefield. It would not just harm the attacked country. Nuclear war would devastate all countries, including the attacker.

The possibility of global devastation is what makes the prospect of nuclear war so very terrifying. And it is also why nuclear weapons are so unattractive for warfare. A weapon that can lead to self-destruction is not a weapon that can be used strategically.

US President Reagan put it in clear words at the height of the Cold War: “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought. The only value in our two nations possessing nuclear weapons is to make sure they will never be used. But then would it not be better to do away with them entirely?”2

40 years after Reagan’s words, the Cold War is over and nuclear stockpiles have been reduced considerably, as the chart shows.

The world has learned that nuclear armament is not the one-way street that it was once believed to be. Disarmament is possible.

But the chart also shows that there are still almost ten thousand nuclear weapons distributed among nine countries on our planet, at least.3 Each of these weapons can cause enormous destruction; many are much larger than the ones that the US dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.4

Collectively these weapons are immensely destructive. The nuclear winter scenario outlined above would kill billions of people—billions—in the years that follow a large-scale nuclear war, even if it was fought “only” with today’s reduced stockpiles.5

It is unclear whether humanity as a species could possibly survive a full-scale nuclear war with the current stockpiles.6 A nuclear war might well be humanity’s final war.

The ‘balance of terror’ is the idea that all involved political leaders are so scared of nuclear war that they never launch a nuclear attack.

If this is achievable at all, it can only be achieved if all nuclear powers keep their weapons in check. This is because the balance is vulnerable to accidents: a nuclear bomb that detonates accidentally – or even just a false alarm, with no weapons even involved – can trigger nuclear retaliation because several countries keep their nuclear weapons on ‘launch on warning’; in response to a warning, their leaders can decide within minutes whether they want to launch a retaliatory strike.

For the balance of terror to be a balance, all parties need to be in control at all times. This however is not the case.

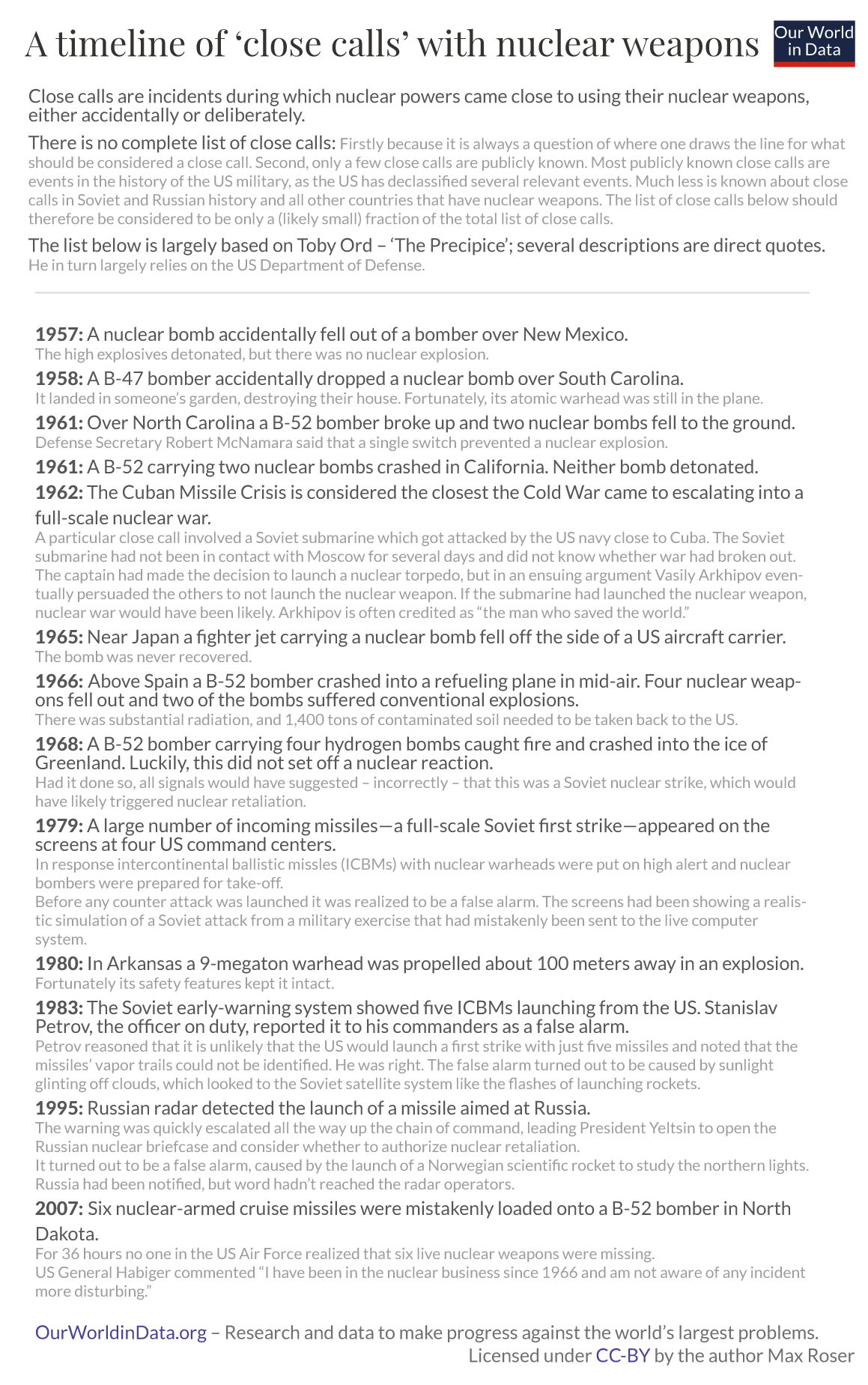

In the timeline, you can read through some of the close calls during the past decades.

The risk of nuclear war might well be low – because neither side would want to fight such a war that would have such awful consequences for everyone on the planet. But there is a risk that the kinds of technical errors and accidents listed here could lead accidentally to the use of nuclear weapons, as a nuclear power can incorrectly come to believe that they are under attack.

This is why false alarms, errors, and close calls are so crucial to monitor: they are the incidents that can push the ‘balance of terror’ out of balance and into war.

Accidents and errors are of course not the only possible path that could lead to the use of nuclear weapons. There is the risk of a terribly irresponsible person leading a country possessing nuclear weapons. There is the risk of nuclear terrorism, possibly after a terrorist organization steals weapons. There is the possibility that hackers can take control of the nuclear chain of command. And there is the possibility that several of these factors play a role at the same time.

A timeline of nuclear weapons ‘close calls’7

Below this post, you find additional lists of close calls, where you find much more information on each of these incidents.

An escalating conflict between nuclear powers – but also an accident, a hacker, a terrorist, or an irresponsible leader – could lead to the detonation of nuclear weapons.

Those risks only go to zero if all nuclear weapons are removed from the world. I believe this is what humanity should work towards, but it is exceedingly hard to achieve, at least in the short term. It is therefore important to see that there are additional ways that can reduce the chance of the world suffering the horrors of nuclear war.8

A more peaceful world: Many world regions in which our ancestors fought merciless wars over countless generations are extraordinarily peaceful in our times. The rise of democracy, international trade, diplomacy, and a cultural attitude shift against the glorification of war are some of the drivers credited for this development.9

Making the world a more peaceful place will reduce the risk of nuclear confrontation. Efforts that reduce the chance of any war reduce the chance of nuclear war.

Nuclear treaties: Several non-proliferation treaties have been key in achieving the large reduction of nuclear stockpiles. However, key treaties – like the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty between the US and Russia – have been suspended and additional agreements could be reached.

The UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which became effective in 2021, is a recent development in this direction.

Smaller nuclear stockpiles: Reducing the stockpiles further is seen as an important and achievable goal by experts.

It is considered achievable because smaller stockpiles would still provide the deterrence benefits from nuclear weapons. And it is important as it reduces the risk of accidents and the chance that a possible nuclear war would end civilization.

Better monitoring, better control: The risk can be further reduced by efforts to better control nuclear weapons – so that close calls occur less frequently. Similarly better monitoring systems would reduce the chance of false alarms.

Taking nuclear weapons off ‘hair-trigger alert’ would reduce the risk that any accident that does occur can rapidly spiral out of control. And a well-resourced International Atomic Energy Agency can verify that the agreements in the treaties are met.

Better public understanding, global relations, and culture: Finally I also believe that it will help to see clearly that billions of us share the same goal. None of us wants to live through a nuclear war, none of us wants to die in one. As Reagan said, a nuclear war cannot be won and it would be better to do away with these weapons entirely.

A generation ago a broad and highly visible societal movement pursued the goal of nuclear disarmament. These efforts were to a good extent successful. But since then, this goal has unfortunately lost much of the attention it once received – and this is despite the fact that things have not fundamentally changed: the world still possesses weapons that could kill billions.10 I wish it was a more prominent concern in our generation so that more young people would set themselves the goal to make the world safe from nuclear weapons.

Below this post you find resources on where you can get engaged or donate, to help reduce the danger from nuclear weapons.

Conclusion

I believe some dangers are exaggerated – for example, I believe that the fear of terrorist attacks is often wildly out of proportion with the actual risk. But when it comes to nuclear weapons I believe the opposite is true.

There are many today who hardly give nuclear conflict a thought and I think this is a big mistake.

For eight decades people have been producing nuclear weapons. Several countries have dedicated vast sums of money to their construction. And now we live in a world in which these weapons endanger our entire civilization and our future.

These destructive weapons are perhaps the clearest example that technology and innovation are not only forces for good, they can also enable catastrophic destruction.

Without the Second World War and the Cold War, the world might have never developed these weapons and we might find the idea that anyone could possibly build such weapons unimaginable. But this is not the world we live in. We live in a world with weapons of enormous destructiveness and we have to see the risks that they pose to all of us and find ways to reduce them.

I hope that there are many in the world today who take on the challenge to make the world more peaceful and to reduce the risk from nuclear weapons. The goal has to be that humanity never ends up using this most destructive technology that we ever developed.

Resources to continue reading and finding ways to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons:

- Hiroshima: John Hersey’s report for the New Yorker about the bombing of Hiroshima, published in August 1946.

- ’80,000 Hours’ profile on Nuclear Security: an article focusing on the question of how to choose a career that makes the world safer from nuclear weapons.

- The ‘Future of Life Institute’ on Nuclear Weapons: this page includes an extensive list of additional references – including videos, research papers, and many organisations that are dedicated to reducing the risk from nuclear weapons.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Charlie Giattino, Hannah Ritchie, and Edouard Mathieu for reading drafts of this and for their very helpful comments and ideas.

Additional lists of close calls with nuclear weapons:

- Future of Life Institute – Accidental nuclear war: A timeline of close calls.

- Alan F. Philips, M.D. – 20 Mishaps That Might Have Started Accidental Nuclear War, published on Nuclear Files

- Josh Harkinson (2014) – That Time We Almost Nuked North Carolina

- Union of Concerned Scientists (2015) – Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons

- Chatham House Report (2014) – Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy authored by Patricia Lewis, Heather Williams, Benoît Pelopidas, and Sasan Aghlani

- Wikipedia – List of Nuclear Close Calls