Why have we made it our mission to publish the “research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems”?

At the heart of it is a simple truth. When we look around us, it is clear that the world faces many very large problems:

- Every year 300,000 women die from pregnancy-related causes, this means that on any average day 830 mothers die

- The majority of the world – around 60% – lives on less than $10 per day.

And almost 10% live in ‘extreme poverty’, they live on less than $2.15 per day. - The world deforested 47 million hectares of forest in the last decade, that’s an area the size of Sweden.

- 60 million children of primary school age are not in school.

- Almost a quarter of the world population – 23% – live in autocratic regimes.

- 14% of the world’s adults do not know how to read and write.

- And 3.7% of all children die before they are five years old. This means that 5.2 million children every year and on any average day the world sees 14,200 child deaths.

This is a list of terrifying problems. And as we don’t hear much that would tell us otherwise, it is easy to be convinced that we can’t do anything about them. Even in the extensive 24/7 news cycles we hear little that suggests it would be possible to make progress against these problems. The same is true for our education — questions like how to end hunger, child mortality, or deforestation are rarely part of the curriculum.

As a consequence it is not surprising that many have the view that it is impossible to change the world for the better. For many large problems the majority in fact believes that they are getting worse.1

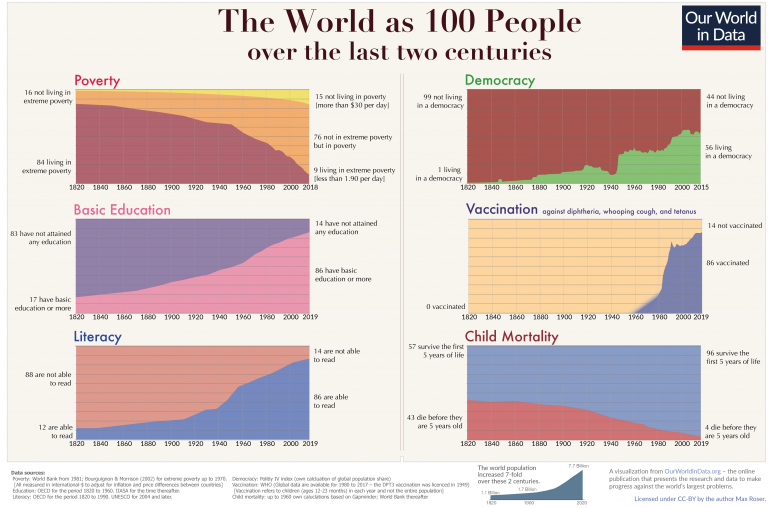

This however, is not the case. We know that it is possible to make progress against these large problems, because we have already done so. Thanks to the efforts of people around the world we have achieved progress against these problems over the course of the last generation. Each of the big problems listed above was much worse in the past.

- The number of women who die from pregnancy-related causes declined from 530,000 women in 1990 to 300,000 per year

- The share living in extreme poverty fell from 38% to less than 10% since 1990 – the share living on more than $10 per day increased from a quarter to a third.

- Global deforestation declined three-fold – from 151 million hectares in the 1980s to 47 million hectares in the 2010s.

- The number of primary school age children who are not in school almost halved from over 110 million in the mid-1990s to 60 million.

- The share of the world living in autocratic regimes declined from 45% in the 1980s to 23%.

- The share of the world’s adults who learned how to read and write increased from 70% in 1980 to 86% today.

- And the share of children who died before they were five years old declined from 9.3% in 1990 to 3.7% – the count fell from 12.5 million dead children per year to 5.2 million.

Because our hopes and efforts for building a better future are inextricably linked to our understanding of the past, it is important to study and communicate the global development up to now. Studying our world in data, and understanding how we overcame challenges that seemed insurmountable at the time, should give us both confidence and guidance to tackle the problems we are currently facing. Living conditions can be improved, we know from the past that they already have been.

For each of the problems we face today we need to also address the difficult question of whether and how we can make progress in the years ahead.

Let’s look at one of the very worst global problems of all from that list above, the death of children. One of the leading causes of death for children is malaria. Every twelfth child death is due to an infection with malaria: 350,000 dead children in one year.2

People who study malaria see a number of reasons that make it very likely that continued progress against this disease is possible. The factors that are holding us back in the fight against malaria are the three factors that often limit our progress:

- More money would make more progress possible: That the world has halved the death toll from malaria within the last 15 years was largely due to insecticide treated bed nets. Sleeping under these nets protects children from the mosquitos that transmit malaria and paying for these nets has been shown to be an effective way to reduce malaria’s death toll.

The problem is that there is not enough funding available to provide bed nets to all children who need them. As a consequence thousands of children die every week. The first reason why children are dying from malaria right now is a lack of funding (you can donate here). - More people that set themselves the goal to work towards progress can make a difference: It is not just more money that can lead to more progress against malaria. It seems very likely that researchers can develop a vaccine against malaria.3 Developing this technology would save many lives and would eventually eliminate the need for millions to sleep under bed nets every night to be protected. What is needed are skilled, hardworking people who understand the problem ahead and set themselves the goal to find a solution for it.

- More attention and the understanding that it is a solvable problem would make more progress possible: Ultimately I don’t think we would see a lack of funding and talented people working on malaria if malaria would get the attention it deserves. 350,000 child deaths per year means 960 dead children on any average day.

Malaria is a large global problem, but it is solvable. What is limiting us is that we don’t understand that.

What is true about malaria is true about many of the problems the world faces. Making progress is hard, but it is possible.

The progress made over the last two centuries has not come to an end in our lifetimes. There are possibilities to make the world a better place, and it is on us to realize this.

The possibility of progress should matter for what we do with our lives

It is possible to lessen substantial problems that many people are suffering under, it is possible to foresee problems that are on the horizon and to reduce these risks, and it is possible to achieve changes that allow the environment around us to flourish. This fact – that progress is not inevitable, but possible – should matter for all of us.

Personally I believe that if we are in a situation in which it is possible to make progress then we are obliged to seek progress. But even if you do not see it as an obligation, you can also see it as an opportunity, a chance to help others, the possibility to do useful work in your life.

Whether you see it as an obligation or as an opportunity, we should ask ourselves what we can do with our money, our contributions to public discourse, our democratic votes, and our lives to help the world to make progress.

Our World in Data publishes research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems.

We made this our mission for two reasons. We want to provide the research and data that those people who are working towards progress need – we want to serve that community.

And we want more people to learn about big problems and to make the decision that they use their energy and resources to contribute to progress – we want to grow that community.

Serve those who work towards progress by providing the research and data on the world’s largest problems

There are already many thousands of people who dedicate their lives to finding solutions to the world’s very large problems.

We know that many of them rely on us: engineers who build safer energy systems, activists who campaign for better health care, scientists who develop new drugs, politicians who want to learn from other countries, teachers who want to inform their students about global poverty, business founders who bring new technologies to the market, and nonprofits that need to decide where to focus their efforts.

Our audience is not defined by who they are, but by what they care about and what they want to do. The people we want to serve are those who work towards progress against large problems.

They all need data and research to understand the problems they are working on – and to decide which problems to work on in the first place. They might want to know which diseases are most prevalent in different parts of the world, how the mix of energy sources compares across countries, or how global access to clean cooking fuels or clean water has changed over time.

It is possible for us to serve these people well because much of the information they need already exists. The problem that we have to solve here is that this existing knowledge is often neither accessible nor understandable – it is often stored in inaccessible databases, locked away behind paywalls and buried under jargon in academic papers. Our goal is to enable those who want to solve large problems to do their best work by increasing the use of evidence and by making the existing knowledge on the big problems understandable and accessible.

Grow the number of people who work towards progress by challenging a culture that doesn’t make it clear that progress is possible

Our second goal is to grow the number of people who decide to contribute to progress against the largest problems.

There are already many people who dedicate much of their time to study big global problems and make it central to their life to seek ways to solve them. But we believe that it is possible to grow this group further and make it a very powerful force within the global culture, because most people are concerned about the world’s problems and would want to contribute to a better future.

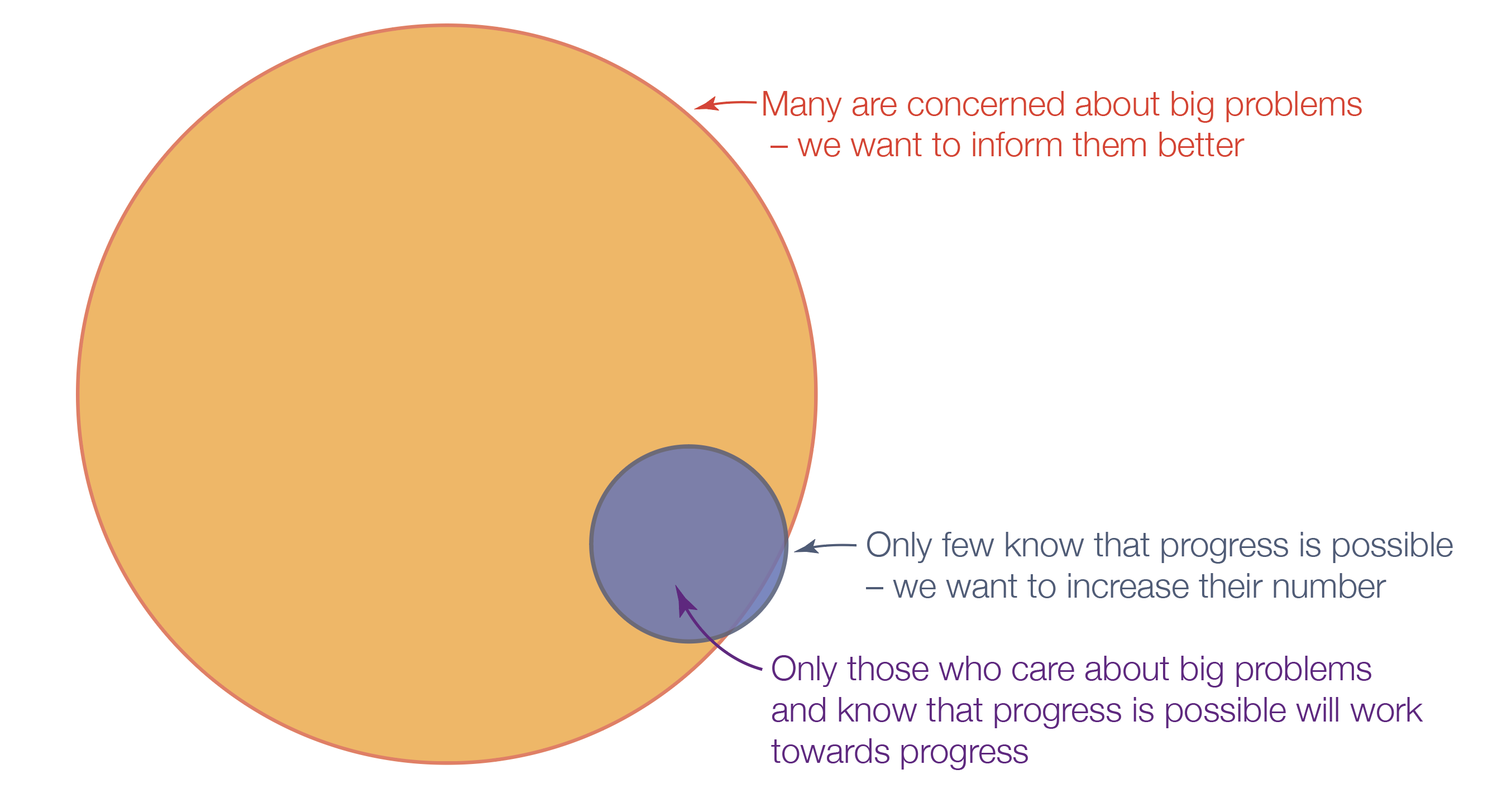

The problem however is that being concerned about big problems is only one precondition for someone to work towards progress. The other key requirement is that a person knows that progress is possible.4

The graphic here is a representation of our argument.

The big orange circle represents the many people who are concerned about big problems. The blue circle represents the much smaller group of people who know that progress is possible. The idea is that it is those who are part of both groups who are taking the decision to work towards progress. We therefore want to grow the blue circle, so that one day it becomes as large as the orange one.

The historian Anton Howes studies the history of innovation and writes “People innovate because they are inspired to do so […]. And when people do not innovate, it is often simply because it never occurs to them to do so. Incentives matter too, of course. But a person needs to at least have the idea of innovation — an improving mentality — before they can choose to innovate.” To make progress we need to have the idea that progress is possible.

It is crucial to grow the number of people who know that progress is possible because almost all the world’s most pressing problems are collective action problems. These are problems that can’t be solved by anyone individually and instead require that many take them seriously and join forces to work towards a solution. When we fail to find solutions to such problems it is because we don’t get started in the first place and this is the situation we are in with many large problems. Instead of changing the world for the better we get stuck in what the social scientist Alice Evans calls a ‘despondency trap’ – not knowing about positive change we mistakenly think that positive change is not possible.

The fact that many believe that progress is impossible should not be too surprising. The powerful forces in our culture are not offering the perspective that progress is possible or even happening. Instead, they are often suggesting that decline is inevitable.

The news media is neither drawing our attention to the large problems we face, nor to the fact that we are making progress against some of them. The news media focuses on daily events, but neither the big persistent problems (such as those listed above) nor the progress against them find a place in news cycles.

Our education systems are also not making us wonder how we can make progress, we are hardly even learning about the progress we made. Few leave school knowing about even the most fundamental achievements in how humanity improved their living conditions. The poor knowledge of the basic facts on global development is evidence for it.

Popular culture too is often detrimental. Frequently it romanticizes a past that wasn’t a reality, and when it speaks about tomorrow it paints a dystopian vision of the future, rather than daring to imagine the better future that is possible.

Sometimes even researchers or activists reinforce the belief that progress is impossible. In their effort to emphasize the severity of the problems they themselves are concerned with, it can happen that they unwittingly present it as hopeless to change the status quo. In the worst cases this achieves the opposite of what they want, passive fatalism rather than effective engagement.

And lastly some intellectuals perpetuate the idea that to believe that progress is possible is a sign of being poorly informed about the true state of the world. The difficulty of some of the world’s problems does warrant some deep pessimism, but not every problem we face justifies a pessimistic outlook and doom and gloom should never become anyone’s intellectual default position. Sometimes the optimist is the realist, and it is the unjustified pessimism itself that is standing in the way of making progress.

Our goal is to change this. By making the research and data on the world around us accessible and understandable, we want to offer a perspective that allows us to understand the difficulty of the problems ahead and their possible solutions.

We at Our World in Data believe that it is possible to grow a culture of people who are seeking solutions to large problems. Within each of the cultural forces I’ve just listed there are people who are working towards change. There are researchers, activists, intellectuals, journalists and teachers who are as keen on finding and communicating the solutions to move forward as they are on explaining the problems ahead. There is a strong culture of progress already, and we hope to expand it further.

The motivation for this work is what I have summarized at the outset: if it is possible to make progress, then we are obliged to make progress. It is not acceptable that much of the world lives in poverty, that children die, that people are hungry, that we are destroying the environment when it doesn’t have to be that way.

We are not saying that everything is getting better

To avoid any doubt it is worth emphasizing what we are not saying.

We don’t believe that everything has gotten better. Some things have gotten much worse. Since the 1940s we’ve had nuclear weapons that can destroy our civilization; burning fossil fuels leads to air pollution that kills millions every year; and the land use for agriculture continues to drive species into extinction.

And it is certainly possible that we remain stuck in the status quo or that things get worse; existential risks do not nearly receive the attention they deserve (Toby Ord’s book is an excellent overview of these risks).

Progress is not inevitable and how the future turns out depends on what we do today. We are not saying we will make progress, but that we can make progress. Whether the problems we face are as old as humanity or were created by ourselves within the last decades, what matters for us now is the same. We should study these problems carefully because we have the possibility to reduce our use of fossil fuels, we can give up on nuclear weapons, and we can work to bring down poverty, child mortality, and hunger.

These two goals belong together – we should study the world’s big problems because it is possible to make progress

A common mistake in thinking about problems and progress is to believe that focusing on one of the two would require to not consider the other. That presenting the evidence for progress would mean to gloss over the problems we still have, or vice versa, that presenting the evidence on global problems would make it necessary to avoid mentioning the progress we’ve made.

For example in an article in the New York Times that relies heavily on our work, Nick Kristof writes: “So I promise to tear my hair out every other day, but let’s interrupt our gloom for a nanosecond to note what historians may eventually see as the most important trend in the world in the early 21st century: our progress toward elimination of hideous diseases, illiteracy and the most extreme poverty.”

I think this is not the right way of looking at it. To study progress should not mean to take a break from the awful problems we face. These two sides belong together, it’s because we know that we can make progress that it is so important to study the problems we face.

To see this consider the alternative. If it wasn’t possible to make progress then there would be little reason to study big problems. All we could care about is to make sure that each of us personally, and perhaps the couple of people close to us, are well and safe. It is the unusual time we live in – the situation that we face large problems against which we can make progress – that makes it an imperative to focus on the problems we face.

We are interested in progress because we are not living in the best of all possible worlds.

Explaining progress and explaining problems belong together. We need to learn about the problems because we can make progress, and we need to learn about progress because we face large problems.

Conclusion

The question that guides our decisions for what we report on Our World in Data is simple: What do you need to know about our world to be able to contribute positively to the world?

Progress means solving problems. This makes it necessary that anyone who wants to contribute to solutions needs to study both:

If you care about problems you need to study progress. The progress we achieved gives us the opportunity to learn how we solved problems in the past and – most fundamentally – to know that progress is possible.

If you want to make progress you need to study problems. Every problem we identify is an opportunity to make progress. To make the world a better place the first step is to understand the problems we are facing today.

Our mission follows from this understanding. Our goal with OurWorldInData.org is to give a wide overview of the big problems the world faces, show that it is possible to make progress against even very large problems, and inspire people to work on these big problems to achieve the progress that is possible.

We want to contribute to a culture that seeks progress – a culture of people deciding to study the very large problems we face and taking the initiative to contribute to progress against them. We want to inform thoughtful people about the world’s large problems and the possibility of progress so that they can become the engineers, politicians, voters, donors, activists, founders or researchers that will solve them.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Hannah Ritchie, Ernst van Woerden, Charlie Giattino, Matthieu Bergel, and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina for reading drafts of this text and for their very helpful comments and ideas.

Our reader Tokio Nagaki kindly translated this text into Japanese: もし私たちが世界の大きな問題に関心があるならば、なぜ進歩について知る必要があるのでしょうか?

Continue reading on Our World in Data: