Even after a century of progress against malaria, the disease remains devastating for millions. The World Health Organization estimates that 216 million suffered from the disease in 2016.1

Fortunately only a small fraction of malaria victims die of the disease. But those who die are the very weakest; three out of four malaria victims are children younger than 5 years old making it one of the leading causes of child mortality in the world today.2

The world is making progress against malaria

In the history of improving population health, the most important progress is made in the prevention of disease; for infectious diseases, this means interrupting its transmission. But humanity’s most ingenious and successful way of transmission interruption – immunization through vaccines – is not yet available for malaria. However, very recent developments are encouraging; at the time of writing (2019) the WHO has rolled out a first large-scale trial of a vaccine.3

But we have other weapons in our arsenal.

One line of humanity’s attack on the mosquito-borne fever is to progressively reduce the area in which malaria is prevalent. A second one is to prevent the transmission of the parasite where it is still prevalent. It is a surprisingly simple technology that stopped transmission and saved the lives of millions in the last few years alone.

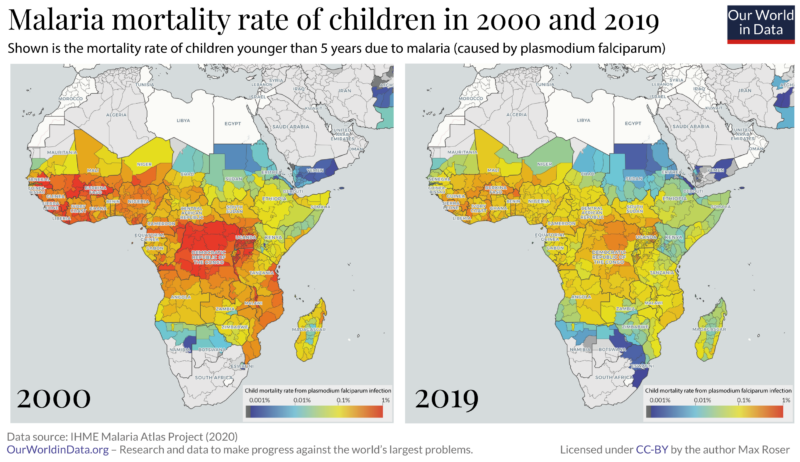

The years since the turn of the millennium were an extraordinarily successful era in the fight against malaria. The two maps shows the change of malaria mortality for children in the region where the disease causes the highest death toll.

From 2000 to 2015 the number of malaria deaths fell by almost 40%, from 896,000 deaths per year to 562,000, according to the World Health Organization.4

A recent publication in Nature5 studied what made this success possible. The focus of the study was Africa, where – as the chart shows – most of the recent reduction was achieved. The researchers found that the single most important contributor to the decline was the increased distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets. The bed nets protect those who sleep under them.

The insecticide used on the bed nets kills the mosquitoes. So a community where a sufficiently high number of people sleep under bed nets the entire community is protected, regardless of whether they themselves use the bed nets. This is similar to the positive externality effect that vaccination has on communities.

The authors of the Nature study estimate that bed nets alone were responsible for averting 451 million cases of malaria in Africa between 2000 and 2015. The other two interventions that were important for the reduction in the disease burden of malaria were indoor residual spraying (IRS) and the treatment of malaria cases with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). The study’s authors estimate that the three interventions averted 663 million cases of malaria in the 15 year period. Insecticide-treated bed nets were by far the most important intervention of the three, preventing 68% of the averted cases.

We can do more

Progress never happens by itself. For millennia our ancestors were exposed to the malaria parasite without defense; the fact that this changed is the achievement of the scientific and political work of the last few generations.

Today we are in the fortunate situation that we have some decades of progress behind us: We can study what worked and use this knowledge to go further.

To continue the improvement in global health more has to be done, and more can be done. Some of the most important research in global development asks the question where donations can do the most good. It’s not always the case that donations do much good. Often it is unfortunately not possible to achieve much progress by donating money because funding is not the limiting constraint or the proposed solution does not actually work. But in some areas we can achieve extraordinary progress by making funding available. A charity evaluator that is doing very rigorous work is ‘GiveWell’ and on the very top of their recommended charities are two organizations that are fighting malaria – the Against Malaria Foundation and the Malaria Consortium.

The diseases many children die from are preventable – we therefore know that we can continue this reduction of child mortality, if we choose to do so. What is different from the past and what makes the deaths of children so appalling today is that we now know how to prevent them.

The evidence shows that the fight against malaria is still underfunded; it will depend on this funding and work whether it is possible to continue our progress against it.7

It requires commitment from governments around the world, but it is also something where each of us individually can contribute. Every one of us can contribute so that we continue to reduce the number of children that die in the world.

- If you want to know more before you donate, GiveWell’s information on malaria can be found here.

- And if you want to donate right away to help the successful fight against malaria you can do so via the page of GiveWell’s recommended charities.