Look at the size of mammals over human history, and we see a clear trend: they’ve gotten smaller.

We now have lots of evidence for this decline in mammal size worldwide.

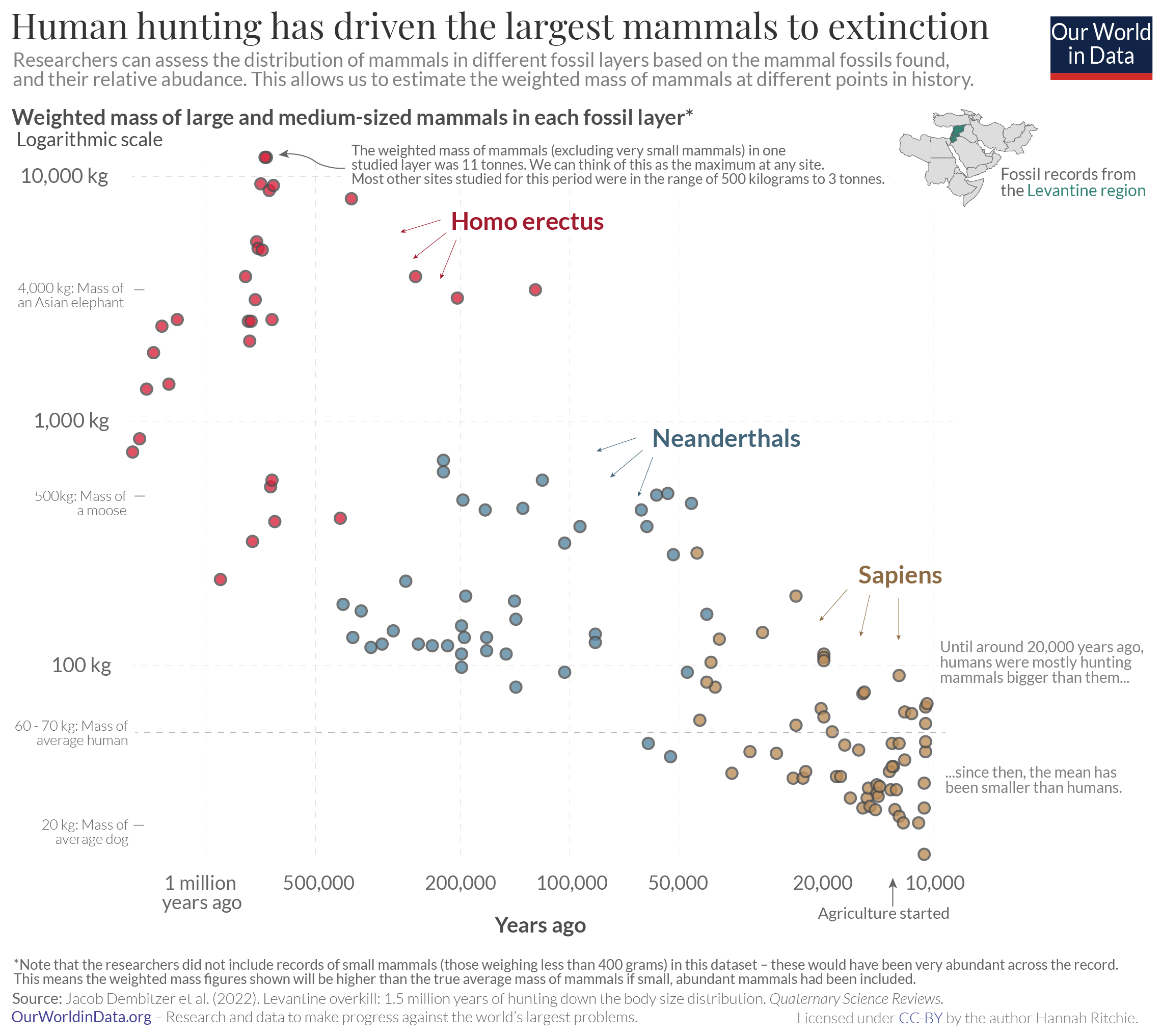

See the changes in the Levantine – the Eastern Mediterranean – where researchers have reconstructed the mass of mammals in the region going back more than one million years.1 To do this, they look at the fossils preserved in sediment layers; these sediment layers can be dated and let us leaf through the pages of the past. It lets us see what animals were around one million years ago, 500 thousand years ago, or ten thousand years ago. Note that the researchers did not include small mammals (those weighing less than 400 grams) in this dataset – these would have been very abundant across the record.

The results are shown in the chart.

We see a steep decline in the average mass of hunted mammals over time. Over the last 1.5 million years, the mean mass of hunted mammals decreased by more than 98%.2

1.5 million years ago, our Homo erectus ancestors roamed the earth with mammals weighing several tonnes. There were the ‘straight-tusked elephants’ (which weighed 11 to 15 tonnes), the Southern Mammoth, and incredibly large hippos. Species-by-species, these majestic animals began to disappear.

The driver of these large ‘megafauna’ extinctions is still contested. Changes in climate are proposed as one cause. But there’s also evidence pointing towards another key culprit: humans.3

The small (our ancestors weighed around 60 kilograms), but big-brained, hominids hunted them to extinction.4

It is staggering how few of our ancestors were around at the time. Globally, there would have been a few million at most.

The record suggests that humans have always hunted the largest mammals.5 This makes sense: it gives a good return on investment. One successful kill could feed a family for a long time. Bigger mammals are also easier to spot and track down.

As we see from the study in the Levantine, until around 20,000 years ago, most hunted mammals were bigger than humans. But since then, the majority have been smaller.

This overhunting of large mammals might have been the catalyst for our ancestors to engineer fine and intricate tools. Once we had run out of big animals to eat, we had to engineer tools to catch the smaller ones.6

12,000 years ago, the average mass of mammals was around 30 kilograms. Around half a human. This is around the time that farming began.7

The disappearance of the largest mammals has happened across the world’s continents

The wipeout of the largest mammals is a global phenomenon that we see across many regions.

Indeed we find it so consistently that one way to estimate the dates at which humans first arrived on different continents is to track the timings of mammal extinctions.

This period during which humans arrived in different world regions and large mammals went extinct across the world’s continents is called the ‘Quaternary Megafauna Extinction’. More than one hundred of the world’s largest mammals were driven to extinction.

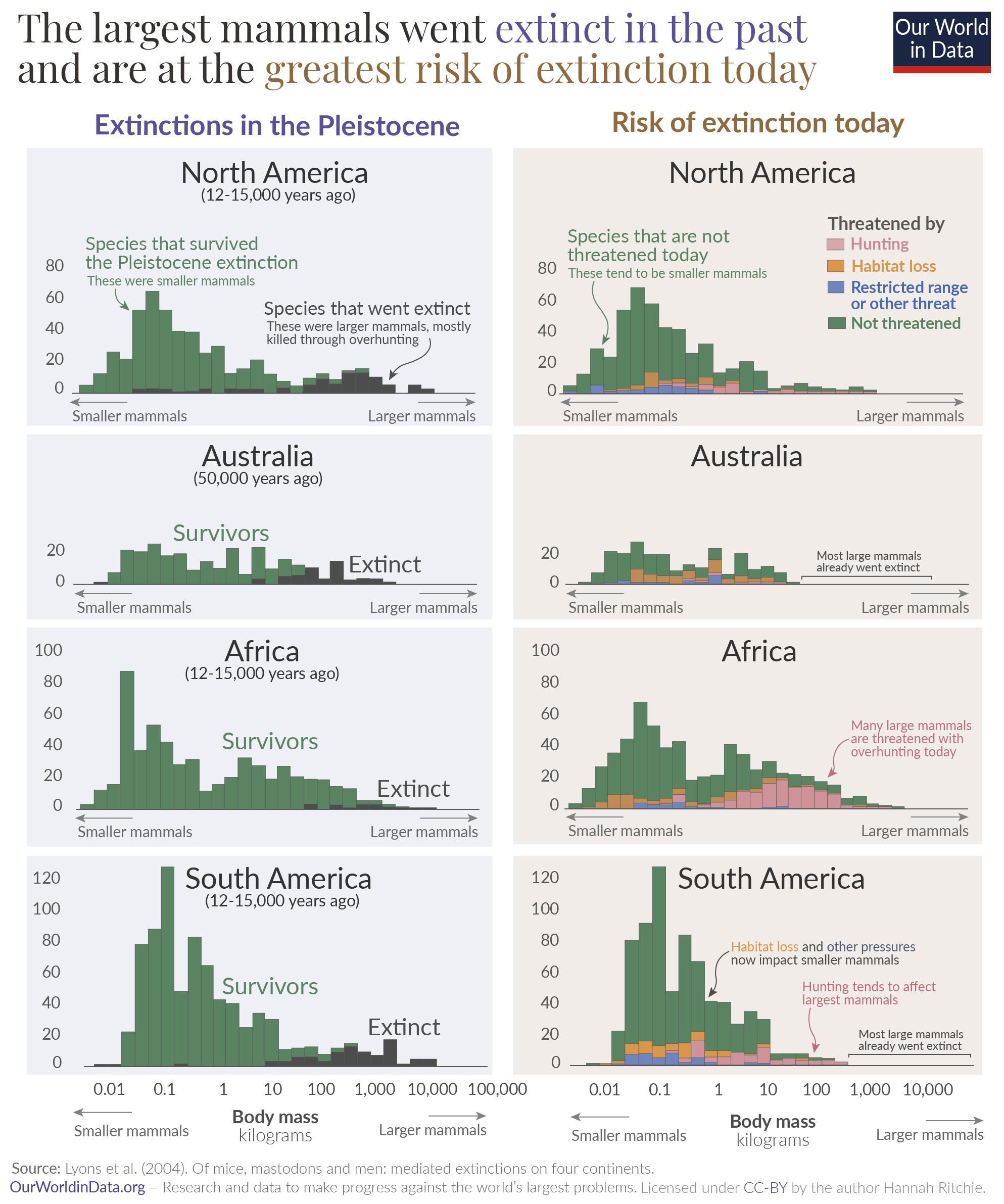

We see this clearly in the chart on the left-hand panel.8 It plots the number of mammals of a given size, from the smallest on the left to the heaviest on the right. In green are the mammals that survived this extinction event. In black are those that did not.

Most of the large mammals went extinct. This is especially true across North and South America and Australia. Africa’s large mammals were spared slightly because mammals had cohabited with humans on the continent for hundreds of thousands of years already. Many of the largest mammals had either gone extinct already or had learned how to protect themselves and co-exist with our ancestors.

What was true in the past is still true today.

Many large mammals are still at risk of overhunting across Africa today. We see this on the right-hand panel of the chart. It shows the current distribution of mammal sizes across the continents and how threatened these mammals are. Note that the modern-day distribution of mammals is not exactly the same as 12 to 15,000 years ago – patterns of biodiversity have evolved since then. But what is consistent is that there is a strong bias toward extinction for the largest mammals, especially from hunting.

In green are the animals not threatened with extinction. These tend to be smaller.

In pink, yellow, and blue are animals at risk of extinction from hunting, habitat loss, or other threats, respectively. Just as in the past, the mammals at risk are the big ones.

This extinction risk for the largest mammals is exacerbated by the fact that they have much slower reproduction times.9 The gestational periods for large animals are longer, which means that it takes a long time for populations to rebuild and recover. Small mammals, even if they’re being hunted, might be able to maintain healthy populations because they can reproduce so quickly.

The biggest mammals are still at the greatest risk of extinction today but it doesn’t have to be this way

The planet’s mammals might be much smaller than they were in the past but the size bias still exists. We might not be overhunting the twelve-tonne mammoths, but it’s still the 5000 kilogram elephants and rhinos that are most at risk of extinction.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Some regions have reversed this trend in recent decades. There has been a resurgence of large mammals in Europe over the last fifty years.10 Populations of elk and brown bears have doubled or even quadrupled in size. The European Bison has been brought back from the brink. And the same is true for many other large mammals in the region.

Legislated protections from hunting, exploitation and habitat loss saved them. The reintroduction of some has stopped them from becoming a long-lost memory.

We see optimistic signs of animal protection elsewhere in the world. The Indian Rhino is making a comeback; in the 1960s there were just 40 rhinos left. Now there are over 4,000. The same is true of the Javan Rhino, and the African elephant.

If we fail to implement effective policies and regulations on hunting; poaching; wildlife trade; and habitat loss, we will simply continue the pattern of the past. But we don’t have to. It’s possible to break this cycle. In doing so we are the generation that will turn the tide on a development that stretches back through millions of years.

Keep reading at Our World in Data

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Max Roser, Daniel Gavrilov, Marcel Gerber, Daniel Bachler, Lars Yencken, Ike Saunders, Fiona Spooner and Bastian Herre for valuable suggestions and feedback on this article.