Summary

Habitat loss is the largest threat to biodiversity. Most of this loss is driven by agriculture. On our current path, researchers project that we’d need an extra 3.4 million km2 of cropland by 2050: an area the size of India and Germany combined. This would destroy habitats for hundreds if not thousands of species of mammals, birds and amphibians.

But we have opportunities to avoid this. Improving crop yields – particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa – would have a massive impact on preserving wildlife. Changing what we eat and how much we waste would also help. If we combine these actions the world would actually need less cropland than we use today. The loss of wild habitats across the world would be minimal. It is possible to feed 10 billion people a healthy, nutritious diet while increasing the space for the world’s wildlife.

Habitat loss is the biggest threat to the world’s wildlife. Nearly all habitat loss is driven by the expansion of agriculture. We chop down forests and convert wild grasslands into farmland to grow crops and raise livestock.

This is nothing new: humans have been transforming the global landscape for millennia.1 Since the end of the last ice-age we’ve lost one-third of the world’s forests – animal populations have been decimated and biodiversity lost as a consequence.

If this development continues it is bad news for many of the world’s animals. To understand the possible impact, David Williams, Michael Clark and colleagues mapped out what the future of agricultural expansion and habitat loss might look like.2 This helps us understand where the biggest threats are.

First, they assessed how much extra cropland the world might need over the next thirty years. They then looked at what this would mean for the world’s wildlife, by mapping this expansion onto existing animal habitats.

Importantly, they also assessed what we could do about it: what are the most effective changes we can make to limit the impact on the world’s wildlife?

Thousands of species are at risk of losing habitat by 2050

Before we look at solutions, let’s first see where we’re headed if things continue on their current path. By 2050 the world population is projected to reach 9.7 billion.3 Africa is expected to have the largest growth, adding over 1.1 billion in the next 30 years. We would expect (and hope) that incomes across the world would increase – especially for those near the bottom.

This means we’ll not only have more mouths to feed, we’ll also have more resource-intensive diets. As we get richer we tend to eat more diverse foods, particularly meat and dairy. These foods require more land, feed, water and other inputs compared to staples such as cereals.

On the production side, the researchers’ business-as-usual scenario assumes that crop yields will continue to increase at similar rates to the past. Some regions, such as Asia and Latin America have seen impressive gains in crop yields over the past 50 years. Unfortunately Sub-Saharan Africa has lagged behind: most of the continent’s increases in agricultural production have come from using more land rather than increases in yields.

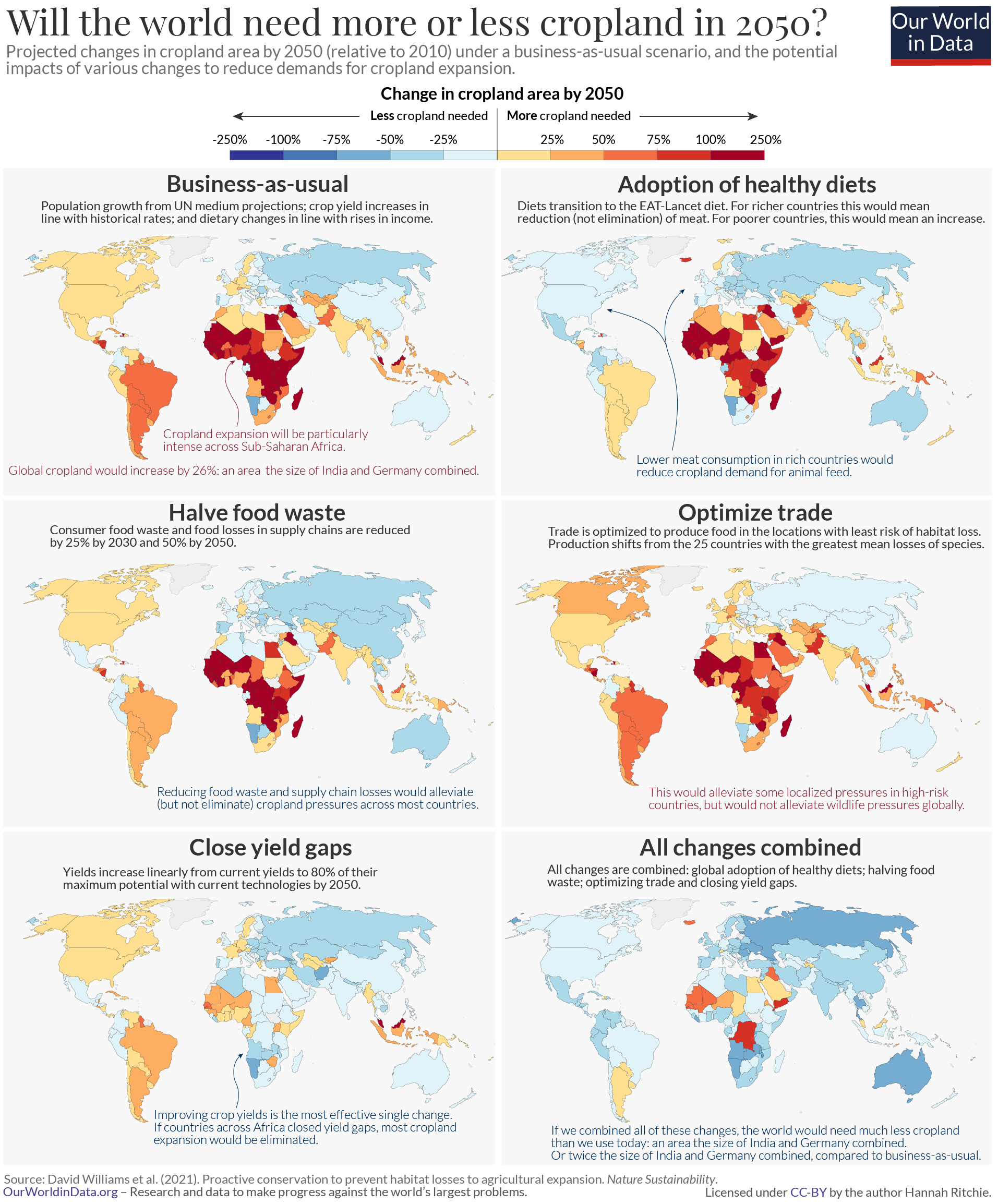

Their results project that by 2050 the world would need 26% more cropland.4 An area the size of India and Germany combined.

Where would most of this growth come from? In the map we see the projected increase in cropland area by country. In blue are countries where cropland area is projected to decrease; in yellow, orange and red are those with an expected increase. We see that cropland expansion would be intense across Sub-Saharan Africa. For many countries, cropland area is projected to more than double.5

This is not that surprising: it will experience most of the world’s population growth in the decades to come. Combined with its slow rates of yield increases in the past, the region will need to use more and more land to grow food.

Most animals could see some of their habitats disappear

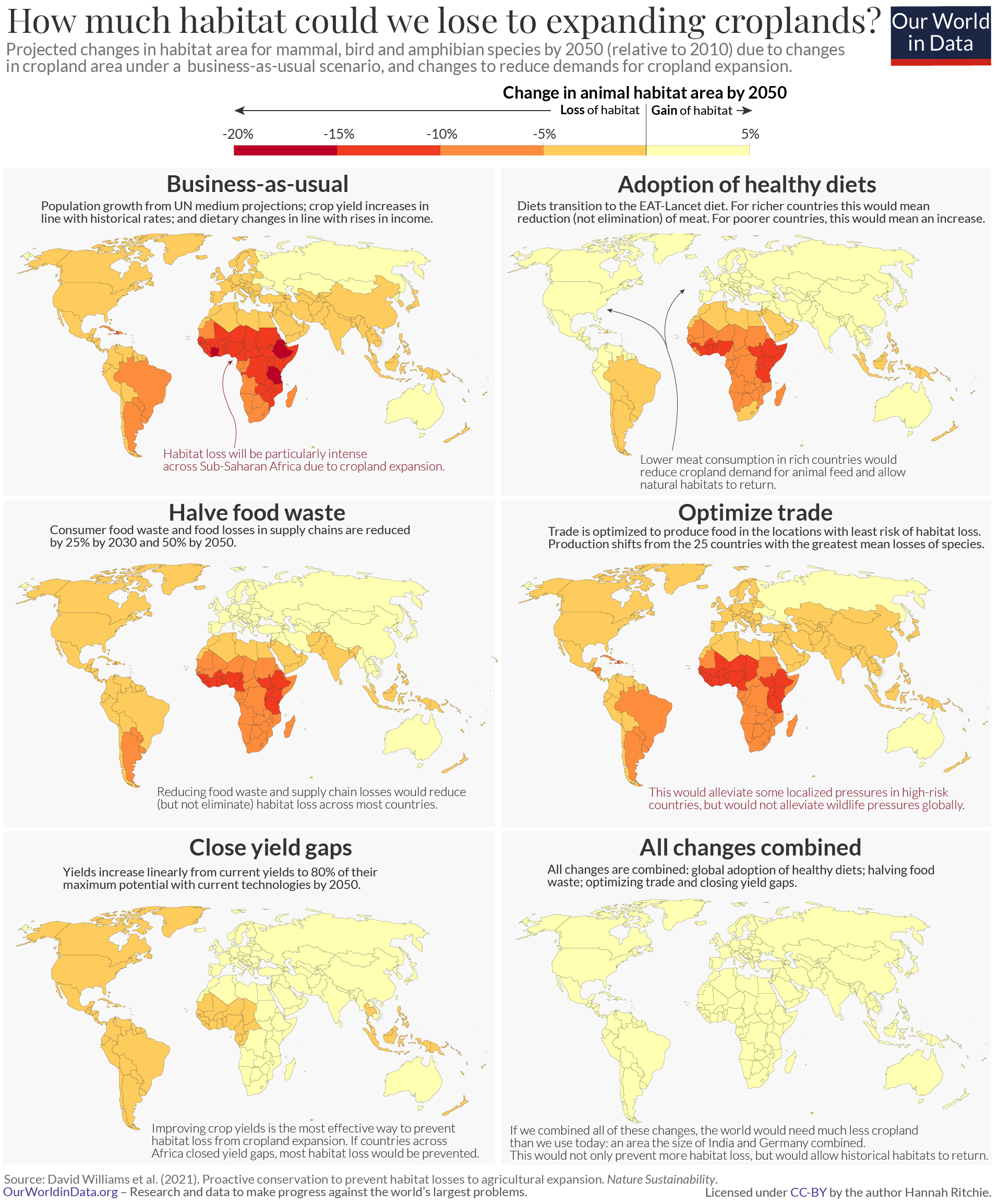

If we need more room for agriculture, we will need to convert natural vegetation and habitat into farmland. What does this mean for the world’s wildlife? Williams et al. (2021) mapped the changes in habitat area for 19,859 species of terrestrial vertebrates: 4,003 amphibian, 10,895 bird, and 4,691 mammal species. They did this using high spatial resolution mapping, creating 1.5 x 1.5 km grids across the world.

Nearly all (88%) of these species would lose at least some of their habitat by 2050.6

Globally, these species would lose 6% of their habitats. The losses in Sub-Saharan Africa would be more than double this figure, at upwards of 12%. The projected habitat loss by region and by country are shown in the charts. In our Data Explorer you can see how these changes would look for specific taxonomic groups – mammals, birds and amphibians individually.

Some animals could see most of their habitats disappear

Even more worryingly, some species risk losing not just some of their habitat, but most of it. Globally, 1,280 species were projected to lose at least 25% of their habitat; 347 species to lose at least half; 96 species at least 75%; and 33 at least 90%.

This means that tens, if not hundreds of the assessed species will be at risk of becoming locally extinct (meaning they will disappear from particular countries). Some even risk becoming regionally or globally extinct. In this map we see the global distribution of these severe losses. Nearly all of them live in Sub-Saharan Africa or Latin America. These two regions account for 93% of the species that are projected to lose at least 25% of their remaining habitat.

This is even more concerning because Sub-Saharan Africa is the last remaining home of some of the world’s largest mammal species.

How can we prevent the loss of wildlife habitats?

What’s obvious is that if we want to save these species we need to reduce the demand for extra farmland. If we can find ways to produce enough food on less cropland we can preserve more habitat for the world’s wildlife. What are our options?

Williams et al. (2021) looked at the impact of a range of possible interventions.

They modeled the following four scenarios:

- Close yield gaps. In this scenario yields increase linearly from current yields to 80% of their estimated maximum potential by 2050.7

- Halve food waste and losses. This scenario assumes that global food wastage and losses are halved.

- Adoption of healthy diets. In this scenario, the researchers investigate what the consequences would be if everyone shifts towards a plant-rich (but not vegan) diet. For most people in rich and middle-income countries, this would mean a reduction in meat and dairy consumption, but it does not eliminate all animal products completely: You can understand what this diet looks like in comparison to current diets in our interactive chart. For many low-income countries, where meat consumption is low, this would actually mean an increase. It’s based on the EAT-Lancet diet, which aims to balance the goals of healthy nutrition and environmental sustainability for a global population.8 Diets vary a lot across the world – often with local cultural food choices. So, this diet does not imply that everyone in the world should eat exactly the same food. Instead, it recommends quantities within a broad food group.

This scenario also assumes that everyone eats a diet that would maintain an average body mass index of 22.5 (the middle of the ‘healthy’ range).9 - Optimize trade. In this scenario agricultural production shifts from ecologically vulnerable countries to those with higher agricultural productivity. Production moves from the 25 countries projected to have the largest habitat losses to countries where less than 10% of species are threatened with extinction.10

The researchers also looked at the impacts if we combined all four of these changes.

Globally, if we implemented all of the above changes (shown as the ‘combined’ scenario) we would need much less cropland than we use today, despite having several billion more people to feed. Global cropland would decline by 3.4 million km2. Remember that under a business-as-usual scenario it was expected to increase by almost exactly this amount (3.4 million km2). So the total ‘saving’ would be nearly 7 million km2. Twice the area of India and Germany combined.

In the maps here we see the change in cropland area across the world by 2050 in each of the scenarios. As we can see, the effectiveness of each intervention varies from country-to-country. The largest benefits in richer countries – across North America, Europe and East Asia – come from consumer options: the adoption of healthy diets, and reductions in food waste.

By far the most effective intervention for poorer countries – particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa – is an increase in crop yields. Rather than cropland area doubling, or even tripling, most countries would keep cropland expansion under 50%. Most under 25%. In fact, many countries would actually see a reduction in cropland area relative to today. This is despite significant increases in population across the region.

Explore these scenarios as interactive charts

Closing yield gaps across Africa is crucial to preventing habitat loss

What does this mean for the loss of wildlife habitats? The good news is that when we combine these changes, all regions would see mean habitat losses of 1% or less by 2050. This means it is possible to feed 10 billion people a healthy, nutritious diet without sacrificing the world’s mammals, birds and amphibians in the process. These goals are not incompatible.

Not only do we see a near-elimination of mean habitat losses, we also dramatically reduce the pressure on the most at-risk species. Our business-as-usual scenario expects that 1,280 species would lose more than 25% of their habitat. Under the combined scenario, this would fall to just 33 species.

In the maps we see the outcome of each intervention by country. Of course, we see the greatest impact by combining all of the approaches.

What stands out across the individual scenarios is the dramatic impact that closing yield gaps has – particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa. If we were able to close these gaps, mean habitat losses across the continent would be just 1%. A stark change compared to our current trajectory.

Improvements in crop yields across Sub-Saharan Africa would not just be good for wildlife. It would also have profound impacts on the lives of more than a billion people across the continent. Farmers would achieve a higher income. Food security would improve. Families would be lifted out of poverty. It offers so many wins.

Human development, population growth and the health of ecosystems are often portrayed as being in conflict. They don’t have to be. Improving yields across lower-income countries is one of the most pressing challenges we face this century. But if we can achieve it, it would not only change the lives of billions of people, it might also preserve the status of hundreds if not thousands of other species.