The lack of access to modern energy sources subjects people to a life of poverty. No electricity means no refrigeration of food, no washing machine, and no light at night.

If you don’t have artificial light, your day is over at sunset. This is why the students in this photo are out on the street: they had to find a spot under a streetlight to do their homework. It’s a photo that shows both the determination of those who were born into poverty, but also the steep odds that they have to work against.

Energy poverty is so common that you can see it from space. In Sub-Saharan Africa 43% of the population do not have access to electricity. The poorest regions in the world are dark at night, as the satellite image shows.

But to understand one of the world’s biggest problems that comes with energy poverty we need to zoom in to what’s happening within family households around the world. More specifically, we need to take a look in the world’s kitchens. In high-income countries, people use electricity or gas to cook a meal. But 40% of the world do not have access to these clean, modern energy sources for cooking. What do they rely on instead?

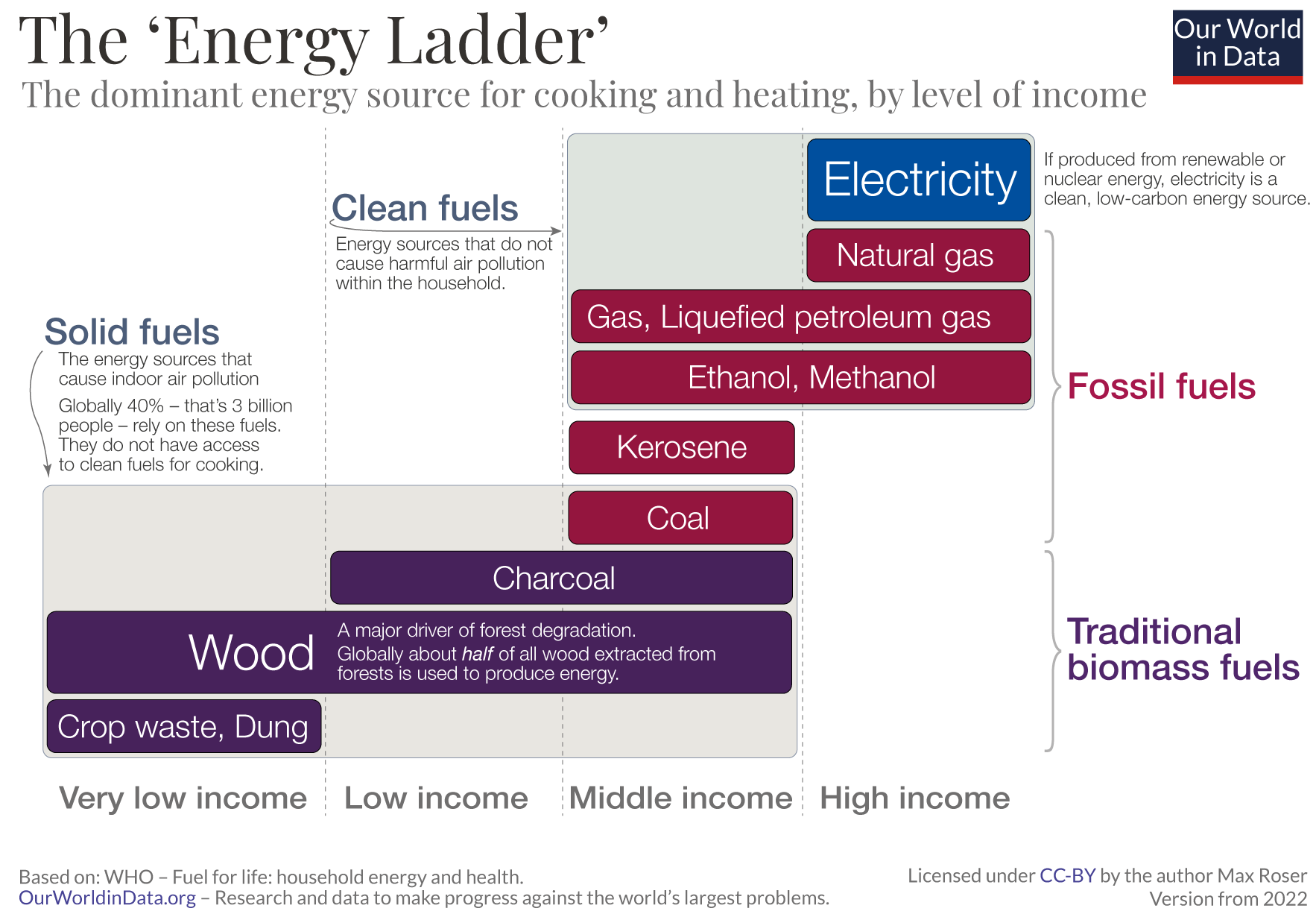

The visualization below is the World Health Organization’s answer.3 The so-called ‘Energy Ladder’ shows the dominant sources of household energy at different levels of income. From very low incomes on the left to high incomes on the right.

The poorest households burn wood and other biomass, like crop waste and dried dung. Those who can afford it cook and heat with charcoal or coal. Burning these solid fuels on open fires or simple stoves fills the room with smoke and toxic chemicals. These traditional energy sources expose those in the household – often women and children – to pollution levels that are far higher than in even the most polluted cities in the world.4

The lack of modern energy comes at a terrible cost to the health of billions of people.

Millions die from diseases that are caused by air pollution within the household. Chronic exposure to pollution in the household leads to pneumonia, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and lung cancer.5 It is the leading risk factor of burns,6 it increases the risk of cataracts,7 and it impacts the health of babies before they are born and leads to a higher rate of stillbirths.8

Global estimates of how many people die from indoor air pollution vary. We need more data on the levels of pollution that people are exposed to; and better research on how this exposure impacts people’s health. The major studies do however all agree that the death toll is extremely high. The IHME estimates that 2.3 million people die from indoor air pollution every year. The WHO estimates the death toll to be substantially higher: 3.8 million annual deaths.9

To put this in perspective, the annual death count from HIV/AIDS is about 1 million and homicides sum up to about 400,000 globally.10

The impacts of indoor air pollution are not limited to the household. As the air escapes the home, indoor pollution is also one of the most important sources of outdoor air pollution, which kills millions more every year. We discuss this in our entry on outdoor air pollution.

Humanity suffered and died from indoor air pollution for thousands of years. As the name ‘traditional’ fuels implies, these were the sources that our ancestors in premodern days relied on.

The use of fire by humans goes back one and a half million years.11 It kept our ancestors warm and protected; it allowed them to hunt and cook. But it also always had the negative side-effect of polluting the air that they breathed. The impact of manmade air pollution is documented in the remains of hunter-gatherers that lived in caves (close to modern-day Tel Aviv) about 400,000 years ago.12 The archeological research suggests that it came from the smoke of indoor fires used to roast meat. High levels of air pollution have also been documented in the preserved lung tissue of Egyptian mummies.13

Accounts of air pollution – indoors and outdoors – are common in the ancient world. The residents of ancient Rome referred to the periods in which their city was cloaked in thick smoke as gravioris caeli (“heavy heaven”). After leaving Rome the philosopher and statesman Seneca wrote in a letter in the year 61:

“I expect you’re keen to hear what effect it had on my health, this decision of mine to leave?

Well, no sooner had I left behind the oppressive atmosphere of the city and that reek of smoking cookers which pour out, along with a cloud of ashes, all the poisonous fumes they’ve accumulated in their interiors whenever they’re started up, than I noticed the change in my condition at once.

You can imagine how much stronger I felt after reaching my vineyards! I fairly waded into my food – talk about animals just turned out on to spring grass! So by now I am quite my old self again.

That feeling of listlessness, being bodily ill at ease and mentally inefficient, didn’t last. I’m beginning to get down to some whole-hearted work.”14

The premodern energy systems that bothered Seneca are a thing of the past for those who live in rich countries today.

But as the ‘energy ladder’ suggests, billions in low- and middle-income countries still do not have access to clean fuels. The two charts here show this.

I’m showing two charts here so we can compare what these two different measures of energy poverty tell us about the world. If you compare the data country-by-country you find that the share that has access to electricity is generally much higher than the share that has access to clean cooking fuels. We can use electricity for cooking, so why would having access to electricity not automatically mean that people have access to clean cooking technology?

It tells us that the cutoff for what it means to have ‘access to electricity’ is very low in these international statistics.15 Having access to electricity means that a household can use it for basic purposes – such as some light at night or for charging a mobile phone – but might not be able to afford electricity for energy intensive purposes, such as cooking. A family that is able to charge their mobile phones often still relies on cheaper fuels, especially wood, for cooking.

The same was true in today’s richest countries in the past. In pre-war London, 65% of households had access to electricity, but only 11% used it for cooking; the majority still relied on wood and coal.16

Globally 40% do not have access to clean fuels for cooking. Four out of ten people – that’s 3 billion people – do not have access to clean, modern energy for cooking today.

The use of wood as a source of energy also has a large environmental impact.

Globally about half of all wood extracted from forests is used to produce energy, mostly for cooking and heating.17 On the African continent the reliance on wood as fuel is the single most important driver of forest degradation.18 In addition to the destruction of the natural environment, the reliance on fuelwood also contributes between 2 and 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions.19

The fact that poor people have to rely on wood as a source of energy is one of the key reasons that deforestation is so rapid in poor countries – and why, on the other hand, forests in richer countries tend to expand in size.20

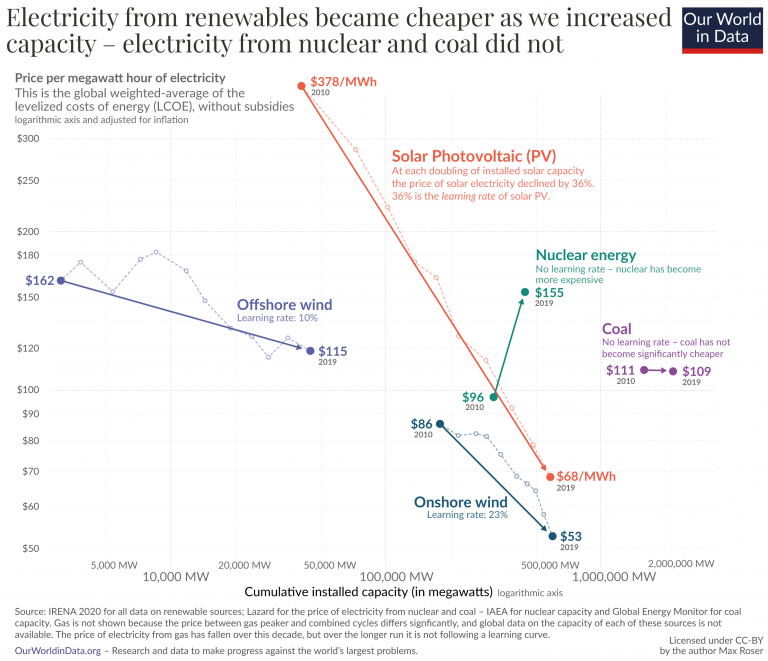

The modernization of the energy system – the transition to safe, low-carbon sources – is not only key to improving the health of billions of people in the world, but also to protecting the environment around us.

Indoor air pollution is a global problem that is very much solvable. The benefits are especially large for women, who not only suffer the largest health consequences but are also mostly responsible for collecting and carrying the wood and biomass to their homes.21

The world is solving this problem. We see this in the chart. Strong economic growth made people around the world richer, and the death rate from indoor air pollution declined.

Globally the death toll from indoor air pollution has declined by 40% since 1990.22

Yet it’s still a massive problem. The map next to it makes this clear. In many countries this very solvable problem is still responsible for over 5% of all deaths.

This is one of the many reasons why growth and electrification are so important for people’s wellbeing and health.

But economic growth is often slow and with 3 billion people in energy poverty it is still a very long way to go. Based on past trends, the International Energy Agency expects that by 2030 there will still be 2.4 billion people without access to clean cooking facilities.23

Is there anything that can be done in the meantime to improve this?

Yes, even at lower incomes it is possible to move away from the most polluting fuel sources.24 China has focused on replacing the coal cookstoves that many relied on until recently and has achieved dramatic reductions in household air pollution. India achieved progress by expanding access to cleaner fuels – especially liquefied petroleum gas.

For many who live in places where modern fuels are not yet available, so-called ‘improved cook stoves’ can be an interim step towards clean cooking. Good stoves burn the fuel more efficiently and are therefore both more environmentally friendly and keep the air in the household cleaner.

Berkouwer and Dean (2019) studied the use of such stoves in Kenya in a randomized control trial to understand how to increase their adoption.25

The research documented that these stoves save households significant sums of money. They reduced fuel costs by $120 per year, equivalent to around one month of income for the average household. As the stove’s market price is only $40 this implies a rate of return of 300% per year.

Poor households are aware of the benefits of these stoves. The problem, the researchers found, is that they cannot afford the upfront cost of $40 to purchase them. This makes a strong case for subsidizing this technology.

On the basis of this study, the Our World in Data team decided to offset our carbon emissions by subsidizing these cooking stoves. We cause greenhouse gas emissions from travel and to power the servers that keep the website running. A key argument for our decision to offset our emissions in this way was that these stoves have additional benefits beyond the emissions reduction. They reduce deforestation and biodiversity losses, provide economic benefits to the households, and reduce indoor air pollution.

Air pollution in the household is a problem that goes back hundreds of thousands of years. Millions of people lost their lives to it over the course of history.

Energy poverty is still the reality for around 3 billion people in the world today. What’s different from the past is that it’s now a solvable problem. What was unavoidable for the ancient Romans or the hunter-gatherers is entirely avoidable today. The millions that die today do not have to, if we find ways to end energy poverty and provide clean modern energy to everyone.

Children who want to do their homework after sunset do not have to sit under street lamps at night.

Key for making progress against energy poverty in the coming years are economic growth, increased production of clean energy, and electrification. Access to energy and clean cooking technologies would mean large benefits for environmental protection, gender equality, and for health.

Indoor air pollution is a problem as old as humanity itself. It is now possible to end it within our lifetimes.

If you want to follow us and support improved cook stoves, you can do so here: burnstoves.com/carbon-credits

Keep on reading Our World in Data:

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Hannah Ritchie for reading drafts of this text and for her very helpful comments and ideas.