Introduction

Although Vietnam reported its first case of COVID-19 on January 23, 2020, it reported only a little more than 300 cases and zero deaths over the following four months.1,2 This early success has been attributed to several key factors, including a well-developed public health system, a strong central government, and a proactive containment strategy based on comprehensive testing, tracing, and quarantining. Lessons from Vietnam’s successful early detection and containment strategy are worth examining in detail so other countries may apply them to their own responses.

Detection: Vietnam has taken a targeted approach to testing, scaled up testing in areas with community transmission, and conducted three degrees of contact tracing for each positive case.

Containment: As a result of its detection process, hundreds of thousands of people, including international travelers and those who had close contact with people who tested positive, were placed in quarantine centers run by the government, which greatly reduced transmission at both the household and community levels. Hot spots with demonstrated community transmission were locked down immediately, and the government communicated frequently with citizens to keep them informed and involved in the public health response.

One of the reasons Vietnam was able to act so quickly is that the country experienced SARS in 2003 and human cases of avian influenza between 2004 and 2010. Therefore, Vietnam had both the experience and infrastructure to take appropriate action. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold and Vietnam relaxes many of its restrictions, monitoring how the case levels change, and studying the reasons for those changes, will be particularly important.

Context

Since the 1980s, Vietnam, a country of nearly 100 million people, has undergone a significant economic transformation. The adoption of economic reforms known as the Doi Moi policies in the mid-1980s turned a centrally planned economy into a socialist-oriented market economy, setting Vietnam on a path to its current middle-income status.

Vietnam has invested heavily in its health care system, with public health expenditures per capita increasing an average rate of 9.0 percent per year between 2000 and 2016.3 These investments have paid off with rapidly improving health indicators. Between 1990 and 2015, life expectancy rose from 71 years to 75 years4, the infant mortality rate fell from 36.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 16.5 deaths in 2018,5 and the maternal mortality ratio plummeted from 139 deaths per 100,000 live births to 54 deaths.6 The 2018 immunization rate for measles in children ages 12 to 23 months is over 97 percent.7

Vietnam has a history of successfully managing pandemics: it was the first country recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be SARS-free in 2003, and many interventions Vietnam pioneered during the SARS epidemic are being used to respond to COVID-19. Similarly, its experience with epidemic preparedness and response measures may have led to greater willingness among people in the country to comply with a central public health response. In fact, a survey conducted in late March by a public opinion research firm found that 62 percent of people in Vietnam believed the level of government response was the “right amount,” ranking higher than any of the other 45 countries surveyed.8

In the wake of the SARS epidemic, Vietnam increased investments in its public health infrastructure, including developing a national public health emergency operations center and a national public health surveillance system.

Vietnam established its national emergency operations center in 2013 and four regional centers in 2016.9 The centers are staffed by skilled personnel, including alumni of the Field Epidemiology Training Program, a program run by MOH’s Department of Preventive Medicine and supported by US CDC and WHO. The program comprises of three curricula that “trains disease detectives in the field.”10 In May 2019, there are 23 alumni in Vietnam.11 This network of emergency operations centers runs exercises and trainings to prepare key stakeholders in government for outbreaks, and it has managed preparedness and response efforts related to measles, Ebola, MERS, and Zika.

Vietnam has long maintained robust systems to collect and aggregate data from public health entities, and it shifted to a nearly real-time, web-based system in 2009. Since 2016, hospitals are required to report notifiable diseases within 24 hours to a central database, ensuring that the Ministry of Health can track epidemiological developments across the country in real time.12 In collaboration with the US CDC, Vietnam piloted an “event-based” surveillance program in 2016 and scaled it up nationally in 2018 based on positive results. Event-based surveillance empowers members of the public, including teachers, pharmacists, religious leaders, community leaders, and even traditional medicine healers, to report public health events. The goal is to identify clusters of people who have similar symptoms that might suggest an outbreak is emerging.13 As another sign of Vietnam’s focus on epidemic preparedness and response, it was one of the first countries to join the Global Health Security Agenda, a group of 67 countries committed to strengthening global efforts in prevention, detection, and response to infectious disease threats, in 2014.14,15

Vietnam’s first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 23, 2020. The patients were a man from Wuhan, China, and his son, who were based in Vietnam.16 The third patient, and the first Vietnamese citizen, was a 25-year-old woman who had traveled to Wuhan on business and returned on January 17, 2020.17 A week after the first case was confirmed, Vietnam formed a national steering committee to coordinate Vietnam’s “whole of government” strategy,18 initially meeting every two days.19 In Vinh Phuc, a northern province about an hour’s drive from Hanoi, provincial leaders locked down a commune named Son Loi, isolated patients and their close contacts in quarantine camps for at least 14 days, and activated community-wide screening at the first evidence of community spread.20

A second wave of cases was discovered on March 6; these cases were imported from new hotspots including Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. By the day after the first case of the second wave was detected, the government had tracked and isolated about 200 people who had close contact, lived on the same street, or were on the same flight from London as the patient.21

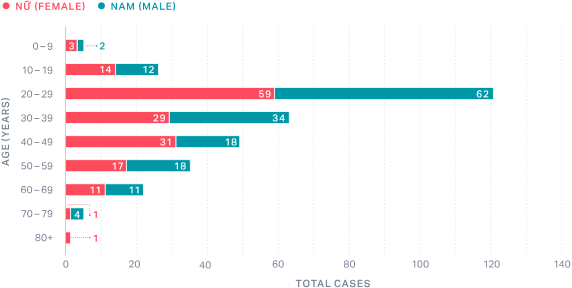

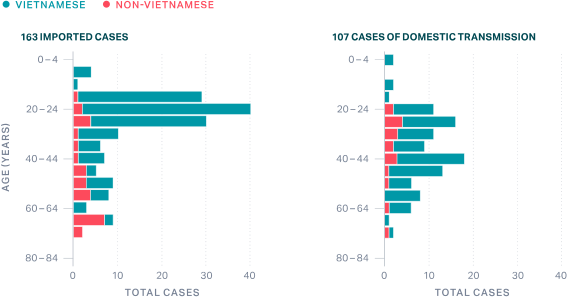

On May 1, a hundred days into the outbreak, Vietnam had confirmed just 270 cases despite extensive testing, with no community transmission since April 15.22 To date, no patients have died from COVID-19 in Vietnam. While there is more to learn about the disease and deaths, some experts speculate that Vietnam’s extremely low obesity rate, combined with its young population (the median age in Vietnam is 30.5, only 6.9 percent of the population is over 65, and the median COVID-19 patient age is 29),23 have contributed to better COVID-19 outcomes. Furthermore, the majority of cases (67 percent as of May 25) in Vietnam were imported from COVID-19 affected countries: first China and then Europe and the United States.

Vietnam Cases by Age and Gender24

Vietnam Imported Cases vs. Community Transmission Cases25

Detect

In late January, the Ministry of Science and Technology hosted a meeting with virologists to encourage the development of diagnostic tests. Starting in early February 2020, publicly funded institutions in Vietnam developed at least four locally made COVID-19 tests that were validated by the Ministry of Defense and the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology. Subsequently, private companies such as Viet A and Thai Duong offered capacity to manufacture the test kits. Most confirmation laboratories where these tests are analyzed use in-house versions of WHO protocol, allowing tests to be widely administered without long wait times. Molecular (e.g., polymerase chain reaction or PCR) testing of respiratory tract samples is primarily used. Rapid diagnostic tests that detect host antibodies have rarely been used.

Development timelines of diagnostic test kits:

- February 7, 2020: Test kit developed by Hanoi University of Science and Technology. Testing method: RT-LAMP (reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification). Cost: US$15. Testing time: 70 minutes.

- March 3, 2020: Test kit developed by Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology. Testing method: real-time RT-PCR (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction). Cost: less than US$21. Testing time: 80 minutes from receiving a sample.

- March 5, 2020: Test kits developed by Military Medical University, commercialized by Viet A. Cost: US$19–$25. Testing method: RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR. Testing time: over one hour (quicker than the two-step Charité protocol) but has testing capacity four times the number of samples as the CDC kit.26 The Viet A test has been certified by the European Union and other authorities and is now being exported to other countries, although WHO certification is still pending as of May 2020.27

- April 28, 2020: Production and launch of the RT-LAMP kit and RT-PCR kit28,29 commercialized by Thai Duong company.

Testing capacity also ramped up quickly, from just two testing sites nationwide in late January to 120 by May. As of May, Sixty-three sites were able to confirm testing (i.e., analyze the results of any given test).30 Given its low case numbers, the country decided on a strategy of using testing to identify clusters and prevent wider transmission. When community transmission was detected (even just one case), the government reacted quickly with contact tracing, commune-level lockdowns, and widespread local testing to ensure no cases were missed. This helps explain why Vietnam has performed more tests per confirmedcase than any other country in the world—by a longshot—even though testing per capita remains relatively low.

Contain

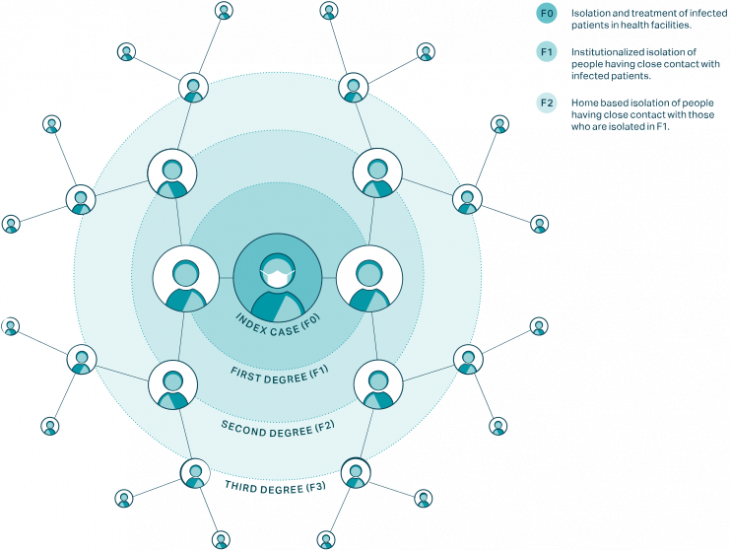

Testing is used as a tool for detection in contact tracing. Contact tracing and quarantine are the key parts of containment. Vietnam’s contact tracing strategy stands out as uniquely comprehensive—it is based on tracing degrees of contact from F0 (the infected person) through F1 (those who have had close contact with F0 or are suspected of being infected), F2 (close contact with F1), and all the way up to F5.

There is a very small window in which to track and quarantine contacts before they become infectious. The incubation period between contact with the virus and start of symptoms is on average five days. Infectiousness begins two days before symptoms. Therefore, there is a period of only three days from the point of contact with a case to find and quarantine contacts before they could potentially infect others. It is critical to move fast, mobilize the contract-tracing apparatus, and locate the contacts.

The process in Vietnam worked as follows:

- Once a patient with COVID-19 is identified (F0), local public health officials, with support from health professionals, security officers, the military, and other civil servants, work with the patient to identify who they might have been in contact with and infected in the past 14 days.

- All close contacts (F1), defined as people who have been within approximately 6 feet (2 meters) of or have prolonged contact of 30 or more minutes with a confirmed COVID-19 case, are identified by this process and tested for the virus.

- If F1s test positive for the virus, they are placed in isolation at a hospital—all COVID-19 patients are hospitalized at no cost in Vietnam, regardless of symptoms.

- If F1s do not test positive, they are quarantined at a government-run quarantine center for 14 days.

- Close contacts of the previously identified close contacts (F2s) are required to self-isolate at home for 14 days.

One noteworthy aspect of Vietnam’s approach is that it identified and quarantined suspected cases based on their epidemiological risk of infection (if they had contact with a confirmed case or traveled to a COVID-19 affected country), not whether they exhibited symptoms. The high proportion of cases that never developed symptoms (43 percent) suggests that this approach may have been a key contributor to limiting community transmission at an early stage.31

Third Degree Contact Tracing in Vietnam32

For SARS, a strategy of identifying and isolating symptomatic people worked because it was infectious only after symptoms started. With SARS-CoV-2, however, infectiousness can occur before onset of symptoms or even in their absence, so such a strategy would be inadequate.

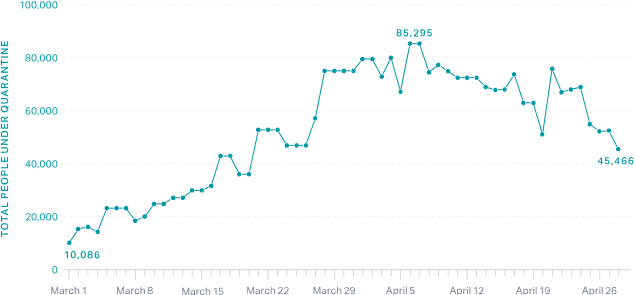

From January 23 to May 1, over 200,000 people spent time in a quarantine facility.33 Those in government run quarantine centers are provided with three meals a day, sleeping facilities, and basic toiletries; reactions to conditions in the quarantine centers on social media have been generally positive.34 Though not popular, “On-demand” quarantine facilities were also established in selected hotels for those who are willing to pay.

On March 10, the Ministry of Health worked with telecom companies to launch NCOVI, an app that helps citizens put in place a “neighborhood watch system” that complements official contact tracing efforts and may have helped to slow transmission of the disease, although the app has drawn criticism from some privacy advocates. NCOVI includes a map of detected cases and clusters of infections and allows users to declare their own health status, report suspected cases, and watch real-time movement of people placed under quarantine.35 On April 15, the app was ranked fourth in downloads among free health and fitness apps in Vietnam’s iOS app store.36 In mid-April, Vietnamese cyber security firm Bkav launched Bluezone, a Bluetooth-enabled mobile app that notifies users if they have been within approximately 6 feet (2 meters) of a confirmed case within 14 days. When users are notified of exposure, they are encouraged to contact public health officials immediately.37

Preventing transmission to health care workers and subsequently back into the community is another important containment strategy. During the SARS outbreak in 2003–2004, dozens of Vietnamese health care workers were infected; apart from the index patient, everyone in Vietnam who died from SARS was a doctor or a nurse.38 Over the past ten years, however, Vietnam has significantly improved hospital infection control by investing in organizational systems, building physical facilities, buying equipment and supplies, and training health workers.

In preparation for the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam further strengthened hospital procedures to prevent infection in health care settings. On February 19, 2020, the Ministry of Health issued national Guidelines for Infection Prevention and Control for COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Disease in Healthcare Establishments. This document provides comprehensive guidance to hospitals on screening, admission and isolation of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases, establishment of isolation areas in hospitals, use of personal protective equipment, cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces, waste management, collection, preservation, packing and transport of patient samples, prevention of laboratory-acquired infection of COVID-19, handling of remains of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases, and guidance for COVID-19 prevention for family members and visitors.

Although most COVID-19 patients in Vietnam were hospitalized at specialty hospitals in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, health care facilities at all levels were prepared to receive them, to avoid overwhelming the acute care system in the event of a larger outbreak. Although Vietnam has not had enough cases to overload hospitals, it is worth noting that only four health care workers have been infected to date.

Vietnam implemented mass quarantines in suspected hot spots based on evolving epidemiological evidence over time (see table).

Vietnam entered a nationwide lockdown on April 1. Initially, the lockdown was set for 15 days, but it was extended to 21 days in 28 out of 63 provinces.

Vietnam COVID-19 Targeted Lockdowns

| Region | Date | Population affected | Details |

| Son Loi Commune (Vinh Phuc Province) | February 13 –March 4 | 10,000 people | At the time, there were 16 cases of COVID-19 in the country, with 6 in Son Loi.39 |

| Truc Bac Street (Hanoi) | March 6–20 | 190 people | Patient 17 (the first confirmed case of the second wave) lived on this street; 66 households were on lockdown.40 |

| Phan Thiet Streets (Binh Thuan) | March 13–April 3 | 150 people | On two streets (Hoang Van Thu and Ngo Sy Lien) where the patient 38 lived, 29 households were on lockdown.41 |

| Van Lam 3 Village (Phuoc Nam Commune, Thuan Nam District, Ninh Thuan Province) | March 17–April 14 | 5,000 people | Two COVID-19 infections, patient 61 and patient 67, led to total lockdown in this area, in which movement restrictions were put in place for all residents, and all 16 entrances to the village were closed off and monitored.42 |

| Thua Loi Village (Ben Tre Province) | March 23–April 20 | 1,600 people | Isolation measures enacted on 480 households after a resident, 17-year-old patient 123, was infected with the virus.43 |

| Bach Mai Hospital (Hanoi) | March 28–April 11 | 4,000—5,000 people | Locked down after 45 people connected to the hospital tested positive for COVID-19. Over 15,000 people who had been associated with the hospital were tested for the virus, and 40,000 people who had come in contact with the hospital sometime before the lockdown were tracked down.44 |

| Ha Loi Village (Me Linh District, Hanoi Province) | April 7–May 6 | 10,000 people | Sealed off during lockdown, with the last detected community cases (apart from Ha Giang patient 268). |

| Dong Van District (Ha Giang Province) | April 22–23 | 7,600 people | The lockdown was put in place before obtaining the test results for suspected cases, and was released the day after when the tests were found negative, exemplifying how quickly the authorities reacted. |

Total People Under Quarantine in Vietnam45

Even before the first cases in Vietnam were confirmed, Vietnam took the first of many steps to implement closures and limit mobility for citizens and international travelers. Most other countries waited to make these types of decisions until numbers were much higher.

Inbound passengers from Wuhan, China, received additional screening before Vietnam’s first case. Visas for Chinese tourists were no longer issued beginning on January 30, just a week after the first case was confirmed.

At the end of the ten-day Lunar New Year holiday on January 31—and with only five confirmed in-country cases—the government mandated that all schools nationwide remain closed.

Flights to and from China were suspended on February 1 and trains were canceled shortly thereafter, on February 5. These restrictions were implemented when cases were in the single digits.

Flights from the Schengen countries and the United Kingdom were suspended on March 15 (after the second wave of cases, traced to people who had been traveling in Europe), and all visa issuance was discontinued on March 18. Vietnam closed borders and suspended all international flights by March 22.

In early February, Vietnam began its practice of placing international arrivals from COVID-19 affected countries in large government-run quarantine centers for 14 days. Vietnam began using the centers for Vietnamese arrivals from China on February 4 and expanded the practice to Vietnamese arrivals from South Korea on March 1—and, finally, for all international arrivals beginning March 20–22. International flights were also diverted away from airports still used for domestic travel.

While leaders in many countries downplayed the threat of COVID-19, the Vietnamese government communicated in clear, strong terms about the dangers of the illness even before the first case was reported. On January 9, the Ministry of Health first warned citizens of the threat; since then, the government has communicated frequently with the public, adding a short prevention statement to every phone call placed in the country, texting people directly, and taking advantage of Vietnam’s high use of social media—64 million active Facebook users are in Vietnam and 80 percent of smartphone users in Vietnam have the local social media app, Zalo, installed.46

In late February, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health released “Ghen Co Vy,” meaning “Jealous Coronavirus,” a well-known pop song given new lyrics and turned into a handwashing public service announcement. The institute asked Khac Hung to rewrite the lyrics and dancer Quang Dang to choreograph dance moves, which ultimately spearheaded a dance challenge on Tik Tok.47 In March, the Ministry of Health sent ten SMS messages to all cell phone users in the country.48 Throughout these communications, the government constantly used the motto: “Fighting the epidemic is like fighting against the enemy.”49 This messaging engendered a community spirit in which every citizen felt inspired to do their part, whether that was wearing a mask in public or enduring weeks of quarantine.

On April 14, Vietnam passed a decree allowing authorities to fine people who use social media to “share false, untruthful, distorted, or slanderous information.” This ordinance has generated opposition from Amnesty International and others. However, according to data from YouGov, as of May 4, 93 percent of the Vietnamese people believe the government is responding “very” or “somewhat” well.50

Conclusion

Certain aspects of Vietnam’s response to COVID-19 may not be replicable in other countries. Its experience with past epidemics encouraged citizens to take significant steps to slow the spread of the virus. Because Vietnam features a one-party government with a chain of command reaching from the national level down to the village level, it is particularly suited to mobilizing resources, implementing public health strategies, and ensuring consistent messages while enforcing regulations stringently.

Many lessons from Vietnam are applicable to other countries, including:

- Investment in a public health infrastructure (e.g., emergency operations centers and surveillance systems) enables countries to have a head start in managing public health crises effectively. Vietnam learned lessons from SARS and avian influenza, and other countries can learn those same lessons from COVID-19.

- Early action, ranging from border closures to testing to lockdowns, can curb community spread before it gets out of control.

- Thorough contact tracing can help facilitate a targeted containment strategy.

- Quarantines based on possible exposure, rather than symptoms only, can reduce asymptomatic and presymptomatic transmission.

- Clear communication is crucial. A clear, consistent, and serious narrative is important throughout the crisis.

- A strong whole-of-society approach engages multi-sectoral stakeholders in decision-making process and activate cohesive participation of appropriate measures.

Vietnam began to lift its national lockdown on April 22. Schools opened between May 4 and May 11. Public transportation, domestic flights, and taxis are now allowed to operate, but international flights remain grounded. Everyone must wear a mask in public.51

Since April 16, Vietnam recorded no new cases of COVID-19 related to community spread. However, as more Vietnamese citizens are repatriated into the country, 54 positive cases have been detected in airports and in quarantine centers.

This next phase of Vietnam’s COVID-19 journey will be important to watch. The big question is how and when will Vietnam open up their borders, and will it be able to maintain this success when it does?

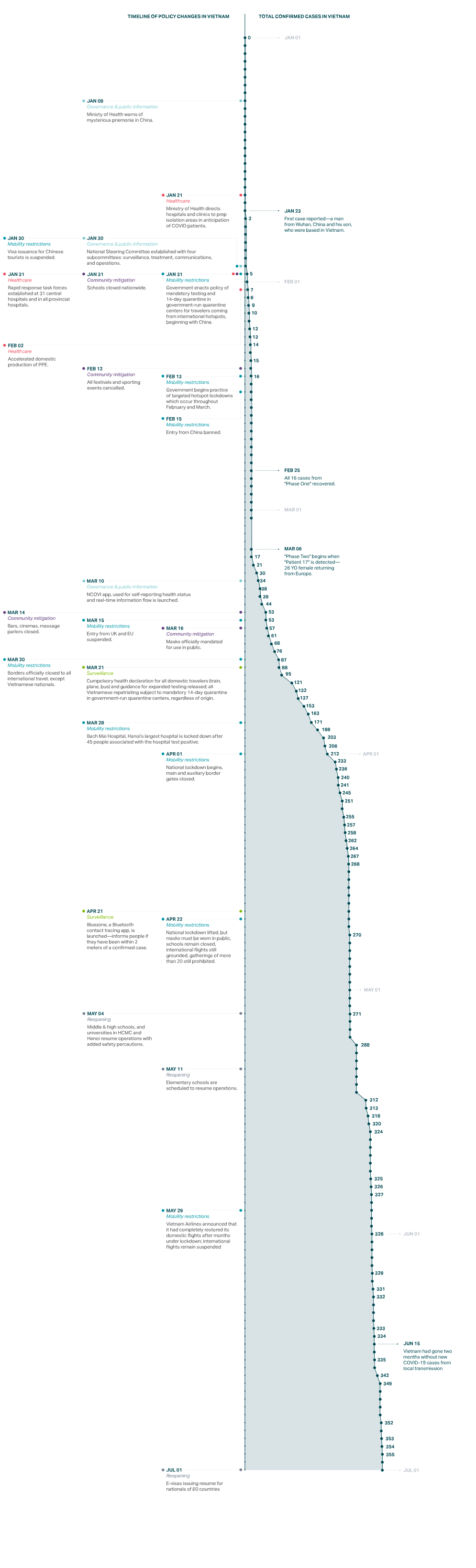

Vietnam: Outbreak and Policy Action Timeline

In-depth explainers on Exemplar countries

This framework identified three countries which provide key success stories in addressing the pandemic: South Korea, Vietnam and Germany. In follow-up articles, in-country experts provide key insights into how these countries achieved this.