A straightforward way to assess the health status of a population is to focus on mortality – or concepts like child mortality or life expectancy, which are based on mortality estimates. A focus on mortality, however, does not take into account that the burden of diseases is not only that they kill people, but that they cause suffering to people who live with them.

Assessing health outcomes by both mortality and morbidity (the prevalent diseases) provides a more encompassing view on health outcomes. This is the topic of this entry.

The sum of mortality and morbidity is referred to as the ‘burden of disease’ and can be measured by a metric called ‘Disability Adjusted Life Years‘ (DALYs). DALYs are measuring lost health and are a standardized metric that allow for direct comparisons of disease burdens of different diseases across countries, between different populations, and over time. Conceptually, one DALY is the equivalent of losing one year in good health because of either premature death or disease or disability. One DALY represents one lost year of healthy life.

The first ‘Global Burden of Disease’ (GBD) was GBD 1990 and the DALY metric was prominently featured in the World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report. Today it is published by both the researchers at the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and the ‘Disease Burden Unit’ at the World Health Organization (WHO), which was created in 1998. The IHME continues the work that was started in the early 1990s and publishes the Global Burden of Disease study.

This entry presents data on burden of health across the world, breakdown by age, types of disability and disease, and regional/country breakdowns. The visualizations which follow can be explored by any country or region using the “Change country” option in the charts below.

Interactive charts on Burden of Disease

Human potential that is lost due to poor health is immense: The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project aims to quantify this loss by estimating the number of healthy life years lost globally. This metric takes into account both, the human life years lost due to early death and the life years compromised by disease and disability. It is a massive study that takes into account thousands of datasets to capture the burden of diseases globally.

55.9 million people died in 2017. If we sum up all life years lost due to premature death – the sum of the differences between each person’s age of death and their life expectancy at that age – we find that the world population lost 1.65 billion years of potential life due to premature death in that year. Disease and disability meant that an additional 853 million years of healthy life years were lost.1

It is hard to get a sense of scale for these enormous numbers. One way to illustrate it is to put it in relation to the global population, which was 7.53 billion in that year. The global burden of disease, viewed in this way, sums up to a third of a year lost for each person on the planet.2

The global distribution of the disease burden

This map shows DALYs per 100,000 people of the population. It is thereby measuring the distribution of the burden of both mortality and morbidity around the world.

We see that rates across the regions with the best health are below 20,000 DALYs per 100,000 individuals. In 2017 this is achieved in many European countries, but also in Canada, Israel, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Kuwait, the Maldives, and Australia.

In the worst-off regions, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, the rate is higher than 80,000 DALYs per 100,000.

The disease burden by cause

Epidemiologists break the disease burden down into three key categories of disability or disease – and this is shown in the chart here: non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [in blue]; communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases [in red], and injuries [in grey].

We provide a more detailed breakdown of what sub-categories fall within each of these three groupings in our Data Quality and Definitions section. We also look at a higher-resolution breakdown within each of these groupings in the sections which follow.

At a global level, in 2017 more than 60 percent of the burden of disease results from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), with 28 percent from communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases, and just over 10 percent from injuries.

The chart also shows a notable shift since 1990, when communicable diseases held the highest share at 46 percent.

This shift in burden towards NCDs result from a significant reduction in communicable and preventable disease as incomes rise and overall health and living standards improve. In high-income nations, NCDs typically account for more than 80 percent of disease burden. In contrast, communicable diseases to be low, at less than 5 percent. The opposite is true in low-income nations; communicable disease still accounts for more than 60 percent across many countries.

In the two charts here we see the breakdown of the disease burden by cause. One chart shows the absolute numbers of DALYs by cause while the other presents share of the total DALYs by each cause.

Non-communicable diseases are shown in blue; communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases shown in red; and injuries shown in grey.

At a global level the largest disease burden in 2017 comes from cardiovascular diseases which account for 15 percent of the total. This is followed by cancers (9 percent); neonatal disorders (7 percent); muscoskeletal disorders (6 percent); and mental and substance use disorders (5 percent).

This attribution varies significantly across the world – these figures and rankings of the disease burden can be explored by country and region using the ‘change country’ option in the charts.

If we look at a lower-income country (e.g. Congo), we notice that communicable and neonatal diseases rank much higher. This is in stark contrast to a typical high-income nation (e.g. United States) where no communicable diseases fall within the top ten. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, muscoskeletal disorders and mental and substance use disorders form the top four health burdens across many upper-middle and high-income nations.

A dedicated IHME website provides a very helpful interactive tool to explore all available data on burden of disease worldwide.

The disease burden by age

In the two chart here we see the breakdown of total disease burden by age group from 1990 onwards. This is shown as the relative breakdown of the total disease burden and by the rates of burden per 100,000 individuals within a given age group.

Overall we see a continued decline in health burden in children under 5 years old; both in relative terms (falling as a share of the total by more than half, from 41 in 1990 to 20 percent in 2017), and in rates per 100,000 (falling more than 50 percent from over 160,000 to less than half in 2017).

Nonetheless, rates of disease burden remain highest in the youngest and oldest in society. DALY rates in under-5s and those over 70 years old remain significantly higher than other age groups. They have, however, seen the most notable declines in recent decades.

At a global level, collective rates across all ages have been in steady decline. This shows that global health has improved considerably over the course of the last generation.

The visualizations here focus on the disease burden resulting from non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

The burden from communicable, neonatal, maternal and nutritional diseases

We see strong differentiation, with high burden across Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia in particular.

Most countries across these regions have DALY losses greater than 25,000 per 100,000 individuals, reaching over 50,000 in the Central African Republic. Rates in Europe and North America, in contrast, are typically greater than ten times lower, below 2500 per 100,000.

There has been a significant reduction in global burden from communicable, neonatal, maternal and nutritional diseases in recent decades, falling from 1.2 billion in 1990 to below 670 million in 2019 (around a 44 percent reduction).

The burden in under-5s represents over half of losses (although this share continues to decline, falling from almost 75 percent in 1990).

The burden from injuries, violence, self-harm and accidents

The category of injuries is broad and encompasses not only accidents (unintentional injuries such as falls, fire and drowning, as well as transport injuries), but also natural disasters and violence including interpersonal violence, conflict, terrorism and self-harm. See Data Quality and Definitions for a breakdown of these categories.

The charts here provide an overview of health burden from injuries.

Road accidents are particularly dominant within this category. However, interpersonal violence and self-harm also constitute a high share of health burden. You will notice that burden attributed to both conflict & terrorism and natural disasters are highly volatile (creating dramatic spikes from year-to-year. We discuss the impact of this volatility on overall trends in the context of death in our blog post here.

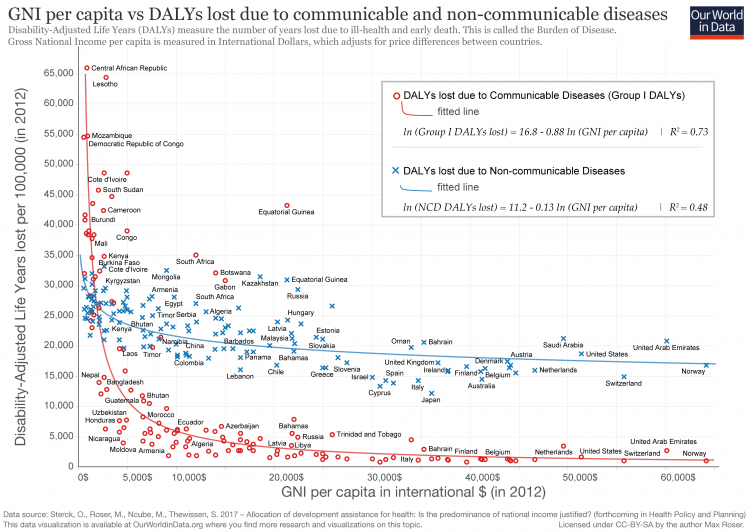

The visualization here shows the relationship between average income – measured by GNI per capita – and the Burden of Disease. The Burden of Disease is disaggregated into the health burden due to communicable diseases and non-communicable diseases.

The chart shows that communicable diseases in particular are closely correlated to average income levels. The relationship that was estimated by Sterck et al. 20173 is shown in the legend. GNI per capita has a strong negative correlation with log DALYs lost due to communicable diseases with an elasticity of -0·88. On the other hand, the non-communicable disease burden is much less strongly associated with average income (the elasticity is estimated to be -0·13). Another conclusion we can draw from this chart is that the relationship between GNI per capita and DALYs lost due to the disease burden of communicable diseases is best captured by a log-log function.

Income and disease burden from communicable diseases

The health burden due to communicable diseases vs GDP per capita is shown in the following visualizations. The correlation between both measures is apparent: both DALY loss rates and the total share from communicable diseases tend to decline with increasing incomes. But despite this correlation, Sterck et al. 20174 find that GNI is not a significant predictor of health outcomes once other factors are controlled for. The first of these other factors is individual poverty – relative to a health poverty line of 10.89 international-$ per day. The second factor is the epidemiological surrounding of a country which captures the health status of neighbouring countries. And the third important factor is institutional capacity.

Income and disease burden from non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

The two charts here highlight two important relationships between non-communicable disease burden and income. The first suggests that rates of burden from NCDs is highest at lower-incomes and tends to decline with development. DALYs lost from NCDs are typically lower at higher incomes.

However, it is also true that NCDs constitute a dominant share of disease burden at higher incomes (often over 80 percent). The fact that both of these relationships are true: that NCD burden tends to decline with development, but increases its share of overall disease burden further highlights that total health burden declines significantly with improving living standards and healthcare.

The fact that NCD DALY losses at low-income are high, but still only constitute a small share of overall health burden emphasises the scale of DALY losses from communicable and preventable diseases which remain.

The visualization shows the relationship between total health burden, given as rates of DALY losses per 100,000 individuals (from all causes) versus average per capita health expenditure (in US dollars). At low levels of health expenditure we see a steep decline in health burden as per capita expenditure increases. However, towards mid-range health expenditure levels we begin to see a significant tailing off of burden reduction.

This diminishing rate of return stagnates at around 20,000 DALYs per 100,000 individuals. Nonetheless, per capita health expenditure at this level of health burden varies by several multiples. Countries such as the United States, Norway and Switzerland have a per capita expenditure over $9,000 per year, but have achieved little or no burden reduction relative to other high-income nations with a per capita expenditure less than half of these figures. Some countries – such as South Korea – have achieved one of the lowest rates of health burden with an expenditure of around $2,000 per capita.

Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost is a standardized metric allowing for direct comparison and summing of burdens of different diseases. Conceptually, one DALY is the equivalent of one year in good health lost because of premature mortality or disability (see Murray et al. 20155). Assessing health outcomes by both mortality and morbidity provides a more encompassing view on health outcomes than only looking at mortality or life expectancy alone.

Three categories of health conditions and burdens are distinguished:

- Communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional diseases;

- Non-communicable diseases (NCDs);

- Injuries (which include violence and conflict).

The sub-categories of disease or health burden, as differentiated in the data provided in this entry from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) are detailed in the table.

| Communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases | Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) | Injuries |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea, lower respiratory & other common infectious diseases | Cardiovascular diseases (inc. stroke, heart disease and heart failure) | Road injuries |

| Neonatal disorders | Cancers | Other transport injuries |

| Maternal disorders | Respiratory disease | Falls |

| Malaria & neglected tropical diseases | Diabetes, blood and endocrine diseases | Drowning |

| Nutritional deficiencies | Mental and substance use disorders | Fire, heat and hot substances |

| HIV/AIDS | Liver diseases | Poisonings |

| Tuberculosis | Digestive diseases | Self-harm |

| Other communicable diseases | Musculoskeletal disorders | Interpersonal violence |

| Neurological disorders (including dementia) | Conflict & terrorism | |

| Other NCDs | Natural disasters |

- Data: DALYs lost

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time span: since 1990

- Available at: At the IHME website or directly via the visualization tool of IHME.