One of the most important trends that we can learn from the work of social scientists and historians is that extreme poverty, as measured by people’s level of consumption, has fallen considerably around the world in the last two centuries. But why should we care? Is it not the case that poor people might have less consumption but enjoy their lives just as much—or even more—than people with much higher consumption levels?

One way to find out is to simply ask. Subjective views are an important way of measuring welfare.

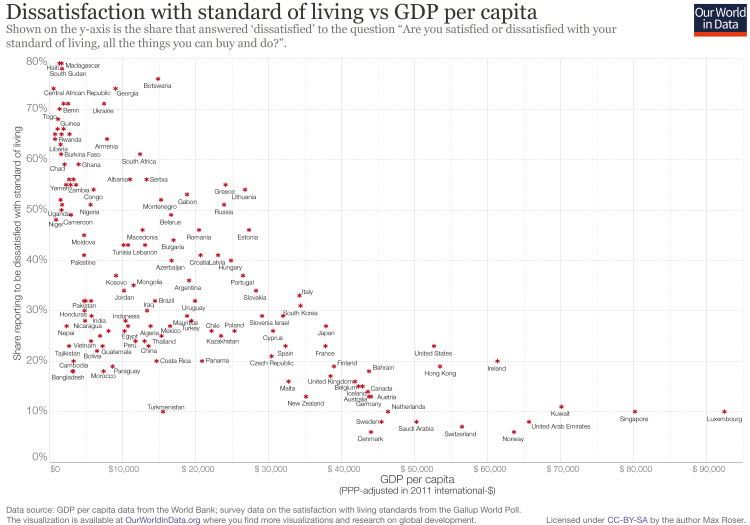

This is what the Gallup Organization did. The Gallup World Poll asked people around the world what they thought about their standard of living—not only about their income. The following chart compares the answers of people in different countries with the average income in those countries. It shows that, broadly speaking, people living in poorer countries tend to be less satisfied with their living standards.

This suggests that economic prosperity is not a vain, unimportant goal but rather a means for a better life. The correlation between rising incomes and higher self-reported life satisfaction is shown in our entry on happiness.

This is more than a technical point about how to measure welfare. It is an assertion that matters for how we understand and interpret development.

First, the smooth relationship between income and subjective well-being highlights the difficulties that arise from using a fixed threshold above which people are abruptly considered to be non-poor. In reality, subjective well-being does not suddenly improve above any given poverty line. This makes using a fixed poverty line to define destitution as a binary ‘yes/no’ problematic. Therefore, while the International Poverty Line is useful for understanding the changes in living conditions of the very poorest of the world, we must also take into account higher poverty lines reflecting the fact that living conditions at higher thresholds can still be destitute.

And second, the fact that people with very low incomes tend to be dissatisfied with their living standards shows that it would be incorrect to take a romantic view on what ‘life in poverty’ is like. As the data shows, there is just no empirical evidence that would suggest that living with very low consumption levels is romantic.

A disregard for or disinterest in poverty estimates that are calculated on the basis of low consumption and income levels is partly explained by the fact that it can be very difficult for people to imagine what it is like to live with very little. Even economists who think a lot about income and poverty find it difficult to understand what it means to live on a given income level. It is just hard to picture what life is like when all you know is a “dollar-per-day” figure.

To address this, Anna Rosling Rönnlund put together a captivating, visual project at Gapminder.org in which she portrays the living conditions of people living at different income levels. In Dollar Street you can find portraits of families and see how they cook, what they eat, how they sleep, what toilets they have available, what their children’s toys look like, and much more.

Dissatisfaction with standard of living vs GDP per capita1