Why is life expectancy in the US lower than in other rich countries?

Americans have a lower life expectancy than people in other rich countries despite paying much more for healthcare. What factors may explain this?

Why do Americans have a lower life expectancy than people in other rich countries, despite paying so much more for health care?

The short summary of what I will discuss below is that Americans suffer higher death rates from smoking, obesity, homicides, opioid overdoses, suicides, road accidents, and infant deaths. In addition to this, deeper poverty and less access to healthcare mean Americans at lower incomes die at a younger age than poor people in other rich countries.

Life expectancy and health expenditure over time, the US is an outlier

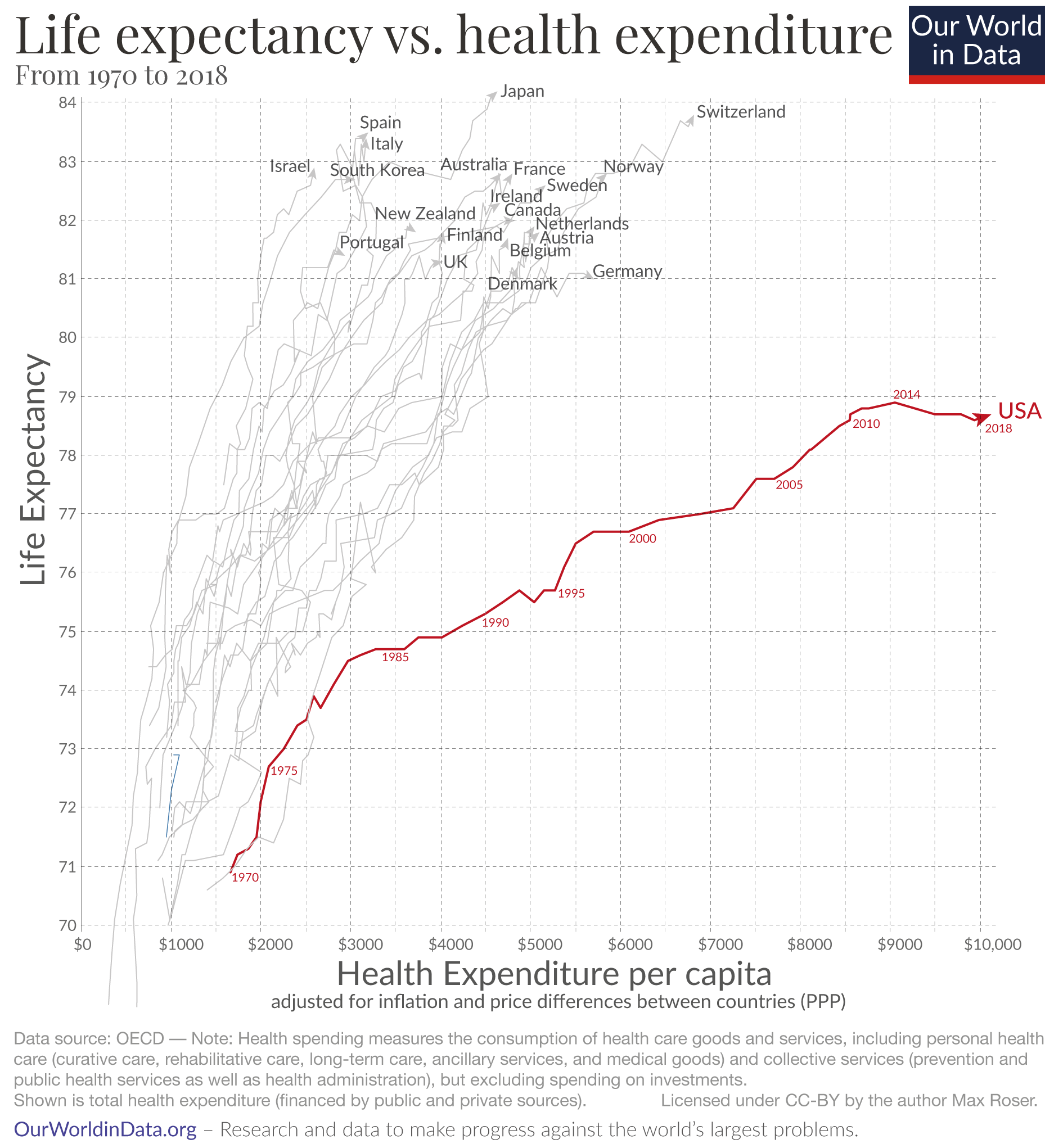

The US clearly stands out as the chart shows: Americans spend far more on health than any other country in the world, yet the life expectancy of the American population is shorter than in other rich countries that spend far less.

The chart here doesn’t just show the latest data points, but how life expectancy and health spending have changed during the last five decades. The arrows start in 1970 and connect the annual data points for both metrics, showing the change over time.

In the 1970s the US didn’t stand out at all, it does so now because life expectancy increased much more slowly than in other countries. At the same time, health spending in the U.S. increased much more rapidly, particularly since the mid-1980s. The consequence of these two exceptional developments is that the US followed the much-flatter trajectory that the chart shows.

The unequal development over recent decades led to an inequality between the US and other rich countries. In the US health spending per capita is up to four times higher, yet life expectancy is lower than in all of these countries.

The US has achieved very substantial progress in health outcomes over the last 140 years: in 1880 the life expectancy of Americans was 39 years, since then it has doubled. But this extremely positive trend has come to an end. While life expectancy for people around the world continued to increase, the life expectancy of Americans has declined since 2014. With the pandemic of 2020 – which already caused more than 225,000 deaths due to COVID-19 and 300,000 excess deaths – it is unfortunately already certain that the decline of life expectancy in the US will continue this year.1

Why is life expectancy shorter in the US?

One could write an entire book on what this chart shows us. Here I want to look at one key question: why is life expectancy in the US shorter? Which causes of death are more common in the US than in other rich countries?

I won’t lay out what is behind the shown long-term improvements in life expectancy (on this you might find our entry on life expectancy helpful) or why we see such large differences in health spending (on this see Lorenzoni, Belloni, & Sassi (2014) and our entry on financing healthcare).2

To understand some of the key reasons that explain the comparatively low life expectancy of Americans, I will look at mortality rates cause-by-cause. Causes of deaths that kill younger people are particularly important – life expectancy captures the average age of death and the average declines strongly when people die at a young age.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking is one of the world’s largest health problems today. 8.1 million people die prematurely from smoking every year. Half of them are people younger than 70.

Smoking was extremely common in today’s rich countries between 1950 and 2000 as the first chart shows. Smoking was more widespread in the US than in Europe or Japan. As a consequence Americans died at higher rates from the consequences of smoking as the second chart shows (most of these people died from lung cancer).

But the chart also shows that smoking peaked earlier in the US. Since there is a lag of two to three decades between the peak of smoking and the peak of smoking mortality, this should be positive news for the US going forward. The country is over this mortality peak and we should expect the decline in lung cancer death rates in the US to continue in the coming years.

Obesity

More than two-thirds of Americans (70%) are overweight and more than one-third (36%) are obese.

Obesity is a key risk factor for many of the leading causes of death in rich countries, including heart disease, diabetes, some cancers, and stroke.3 Estimates of the death rate from obesity-related factors in the US are higher than for other countries as the chart shows. To improve population health it will be key for all countries to make progress against obesity, for the US it is especially important.

Homicides

This chart compares homicide rates in the US with a number of other rich countries. No matter which other rich country you add to the chart, you won’t find one with a higher homicide rate. The homicide rate in the US is much higher than in other rich countries.

As most homicide victims are young, this contributes to the lower level of life expectancy in the US in comparison with other rich countries.

This is of course important but it cannot explain the growing inequality in life expectancy between the US and other countries over time. Over the last few decades, homicide rates have declined more in the US than in other rich countries. In relative terms, the faster decline of homicide rates in the US has reduced the relative difference in life expectancy between countries.

Opioid overdoses

This chart shows the death rate from opioid overdoses. This is a cause of death where the US very clearly stands out.

In the US the death rate has increased more than 10-fold since 1990, while opioid overdoses have remained an extremely rare cause of death in other countries. No other country in the world has seen a surge in opioid overdose deaths as large as the US. Today the US has by far the highest opioid overdose death rate.

Opioid overdoses are still thankfully a relatively rare cause of death overall (it is the cause of death of 1.6% of Americans), but these deaths affect life expectancy because many victims are relatively young.

Ruhm (2017) carefully studied opioid mortality in the US on a local level and found that the availability and the prescription of opioid-based painkillers is the main driver of the opioid mortality surge in the US.4 This contributes to an explanation of both aspects that the first chart above highlights: lower life expectancy and higher healthcare costs.

Suicides

Suicides have increased slightly over the past generation in the US, as the chart here shows.

This is not the case in manyotherrichcountries – you can switch to any other country in the world in the chart. Also, globally suicide rates have fallen substantially over recent years.

The US stands out in particular in suicides from firearms, which are much rarer in countries around the world.

Suicides are also among the few causes of death that are a high risk for younger people. The age distribution of suicides and the fact that suicides are rising in the US and falling in many other rich countries explain why this is another cause of death that contributes to the divergence in life expectancy that we are trying to explain.

Road accidents

Deaths in road accidents are also much more common in the US than in most other rich countries.

The chart shows that in many countries road deaths are at least 50% less common.

Most Americans who die in road accidents are young, which is why this cause of death contributes significantly to the gap in life expectancy between the US and other countries.

Poverty and economic inequality

So far we’ve only covered causes of deaths where the US stands out as having a higher death rate. But the US also stands out in having higher economic inequality and poverty than other rich countries,5 and this matters for the health outcomes as well.

While Americans have a higher average income than people in most other rich countries, the incomes of the poorest Americans are lower than the incomes of the poorest people in other rich countries.

Infant mortality – the share of infants that don’t survive the first year of their life – is higher in the US than in just about every other rich country. You can again add countries to the chart here. High infant mortality matters very much for life expectancy as the very short life span pulls down the average strongly.

The research by Alice Chen, Emily Oster, and Heidi Williams (2016) shows that while the mortality rates for babies of well-off people in the US and European countries are similar, there are larger differences between the mortality rates of the infants born to poorer people.6 As the authors put it: "the observed higher US postneonatal mortality relative to Europe is due entirely, or almost entirely, to higher mortality among disadvantaged groups."

Not just the mortality of infants is higher in the US, but maternal mortality is also much higher. And while maternal mortality is falling in almost all countries in the world the death of mothers is becoming more common in the US.

Poorer Americans are already substantially worse off within the first year of life. Over the life course, the disadvantages accumulate. The inequality in life expectancy is large in the US, the difference between the poorest 1% and the richest 1% in the US is 14.6 years.7 And this income gradient in life expectancy has widened recently.

The low life expectancy of poorer Americans is a big part of why the average life expectancy in the US is lower than in other rich countries. Kinge et al (2019) study the difference between the US and Norway.8 Like the US, Norway is exceptionally rich, but it is much less unequal. As a consequence Norwegians in the lower half of the income distribution are richer than Americans in the lower half of the income distribution. The lower level of income inequality in Norway is mirrored by a lower inequality in life expectancy. The life expectancy of Norwegians in the lower-middle-income segment is about 3 to 4 years higher than the life expectancy of Americans in that same income segment.

The world as a whole has achieved very rapid progress; global life expectancy has increased to over 70 years. The US isn’t keeping up with this progress – because of the high inequality and slow development of the US, there are now 19 US counties where people have a lower life expectancy than the global average.9

Access to healthcare

Among rich countries, the US stands out as a country where the population does not have universal access to health insurance.

The chart here shows the situation in 2011, unfortunately, the latest global data that I am aware of. In most rich countries it is the case that everyone is covered by health insurance, but not in the US. The US has expanded healthcare coverage in recent years, but a significant share of its population is still uninsured.10

This explains part of the difference in life expectancy according to the extensive study of the US National Research Council11 The authors note that for older Americans this is a small factor, due to the availability of Medicare, but overall conclude: “Certainly, the lack of universal access to health care in the United States has increased mortality and reduced life expectancy.”

Conclusion

In addition to my overview I recommend two research publications that study in detail why in terms of life expectancy the US is falling behind other rich countries.12 You can also use our extensive data presentation on causes of death to explore this yourself.

Every country should and can do better in this respect, but a particular weakness of the US is a lack of success in preventing poor health. Many of the important factors – smoking, obesity, violence, poverty – are not about providing better healthcare for those that need it, but about preventing poor health outcomes in the first place.

The failure to prevent poor health is a factor that is contributing to both developments shown in the first chart. They worsen the health of the American population and they are expensive for the healthcare system.

Now, in the middle of a global pandemic, there is little reason to hope that the US can reverse the recent trend of declining life expectancy. For the years ahead a focus on the high death rates of causes of deaths that kill younger people can be the starting point to get the US population back on track towards a longer and healthier life.

Endnotes

Guillaume Marois, Raya Muttarak, Sergei Scherbov (2020) – Assessing the potential impact of COVID-19 on life expectancy. In Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238678

Lorenzoni, L., Belloni, A., & Sassi, F. (2014) – Health-care expenditure and health policy in the USA versus other high-spending OECD countries. The Lancet, 384(9937), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60571-7

Ford, E. S., Williamson, D. F., & Liu, S. (1997). Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. American journal of epidemiology, 146(3), 214-222.

Resnick, H. E., Valsania, P., Halter, J. B., & Lin, X. (2000). Relation of weight gain and weight loss on subsequent diabetes risk in overweight adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 54(8), 596-602.

Eckel, R. H., & Krauss, R. M. (1998). American Heart Association call to action: obesity as a major risk factor for coronary heart disease. Circulation, 97(21), 2099-2100.

Bianchini, F., Kaaks, R., & Vainio, H. (2002). Overweight, obesity, and cancer risk. The lancet oncology, 3(9), 565-574.

Christopher J. Ruhm (2017) – Deaths of Despair or Drug Problems?

See World Bank data on the Gini coeffient and Brady, D., & Parolin, Z. (2020). The Levels and Trends in Deep and Extreme Poverty in the United States, 1993–2016. Demography. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00924-1

Alice Chen, Emily Oster, and Heidi Williams (2016) – Why Is Infant Mortality Higher in the United States Than in Europe? – Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2016 May; 8(2): 89–124. doi: 10.1257/pol.20140224.

Raj Chetty, Michael Stepner, Sarah Abraham (2016) – The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. In JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750-1766. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4226

Kinge JM, Modalsli JH, Øverland S, et al. (2019) – Association of household income with life expectancy and cause-specific mortality in Norway, 2005-2015. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1916-1925. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.4329

The latest county-by-county data on life expectancy published here by the IHME refers to 2014. Global life expectancy in 2014 was 71.4 years according to the UN.

These counties have a lower life expectancy than that 1. Oglala Lakota County (Shannon County), South Dakota; 2. Union County, Florida; 3. Todd County, South Dakota; 4. Sioux County, North Dakota; 5. Buffalo County, South Dakota; 6. Owsley County, Kentucky; 7. Breathitt County, Kentucky; 8. McDowell County, West Virginia; 9. Perry County, Kentucky; 16. Kusilvak Census Area, Alaska; 10. Tunica County, Mississippi; 11. Holmes County, Mississippi; 12. Dewey County, South Dakota; 13. Coahoma County, Mississippi; 17. Wolfe County, Kentucky; 14. Leslie County, Kentucky; 15. Roosevelt County, Montana; 18. Phillips County, Arkansas; 19. Mingo County, West Virginia.

Barack Obama (2016) – United States Health Care Reform: Progress to Date and Next Steps. In JAMA. 2016;316(5):525-532. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9797

National Research Council (2011) – Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High-Income Countries. E.M. Crimmins, S.H. Preston, and B. Cohen, Eds. Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

The first one is this excellent report by the National Research Council that examines the evidence on competing explanations for the divergent trends with a focus on finding the opportunities on health-related interventions for the US to narrow this gap.

National Research Council (2011) – Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High-Income Countries. E.M. Crimmins, S.H. Preston, and B. Cohen, Eds. Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

The second one is this more recent publication in JAMA:Steven H. Woolf and Heidi Schoomaker (2019) – Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959-2017. In JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996-2016. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.16932

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2020) - "Why is life expectancy in the US lower than in other rich countries?". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://staging-owid.netlify.app/us-life-expectancy-low' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-us-life-expectancy-low,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {Why is life expectancy in the US lower than in other rich countries?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2020},

note = {https://staging-owid.netlify.app/us-life-expectancy-low}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.