Several academic studies have shown that trade liberalization often has a negative impact on wages and employment for specific groups of people – from industry workers in the US to farmers in India. These studies are important and informative, but there are some nuances to keep in mind.

- Narratives that focus on winning and losing countries miss the point. Globalization impacts the standard of living of different types of workers to different degrees within countries, in all countries.

- The negative effects of trade on earnings tend to be concentrated in specific areas and industries. Aggregating across regions and firms gives us a different picture.

- Trade also affects consumer prices; not just wages. Most studies approximate the impact of trade on welfare by looking at how much wages can buy, using as reference the changing prices of a fixed basket of goods. This fails to consider welfare gains from increased product variety and obscures complicated distributional issues, such as the fact that poor and rich individuals consume different baskets so they benefit differently from changes in relative prices. Studies measuring the distribution of welfare gains, across all the main relevant welfare channels are only beginning to emerge.

What’s the impact of trade on jobs and wages?

The most famous study looking at this question is Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013): “The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States”.1

In this paper, Autor and coauthors looked at how local labor markets changed in the parts of the country most exposed to Chinese competition, and they found that rising exposure increased unemployment, lowered labor force participation, and reduced wages. Additionally, they found that claims for unemployment and healthcare benefits also increased in more trade-exposed labor markets.

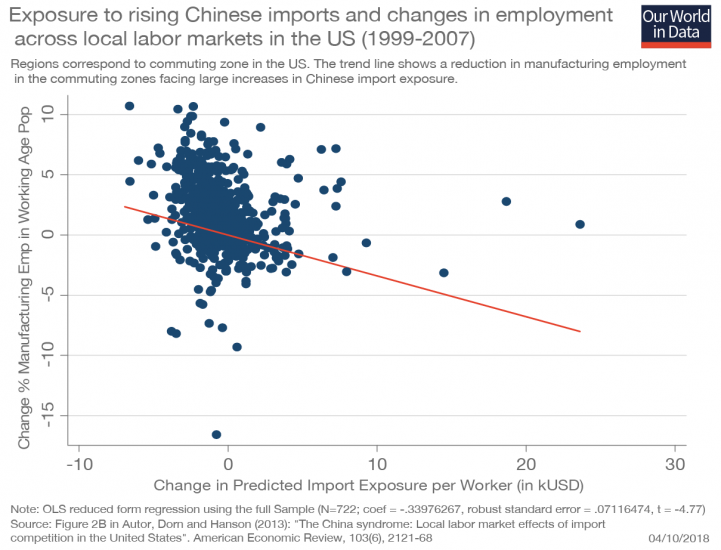

The visualization here is one of the key charts from their paper. It’s a scatter plot of cross-regional exposure to rising imports, against changes in employment. Each dot is a small region (a ‘commuting zone’ to be precise). The vertical position of the dots represents the percent change in manufacturing employment for working age population; and the horizontal position represents the predicted exposure to rising imports (exposure varies across regions depending on the local weight of different industries).

The trend line in this chart shows a negative relationship: more exposure goes together with less employment. There are large deviations from the trend (there are some low-exposure regions with big negative changes in employment); but the paper provides more sophisticated regressions and robustness checks, and finds that this relationship is statistically significant.

This result is important because it shows that the labor market adjustments were large. Many workers and communities were affected over a long period of time.2

But it’s also important to keep in mind that Autor and colleagues are only giving us a partial perspective on the total effect of trade on employment. In particular, comparing changes in employment at the regional level misses the fact that firms operate in multiple regions and industries at the same time. Indeed, Ildikó Magyari recently found evidence suggesting the Chinese trade shock provided incentives for US firms to diversify and reorganize production.3

So companies that outsourced jobs to China often ended up closing some lines of business, but at the same time expanded other lines elsewhere in the US. This means that job losses in some regions subsidized new jobs in other parts of the country.

On the whole, Magyari finds that although Chinese imports may have reduced employment within some establishments, these losses were more than offset by gains in employment within the same firms in other places. This is no consolation to people who lost their job. But it is necessary to add this perspective to the simplistic story of “trade with China is bad for US workers”.

Exposure to rising Chinese imports and changes in employment across local labor markets in the US (1999-2007) – Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013)

Another important paper in this field is Topalova (2010): “Factor immobility and regional impacts of trade liberalization: Evidence on poverty from India”.4

In this paper Topalova looks at the impact of trade liberalization on poverty across different regions in India, using the sudden and extensive change in India’s trade policy in 1991. She finds that rural regions that were more exposed to liberalization, experienced a slower decline in poverty, and had lower consumption growth.

In the analysis of the mechanisms underlying this effect, Topalova finds that liberalization had a stronger negative impact among the least geographically mobile at the bottom of the income distribution, and in places where labor laws deterred workers from reallocating across sectors.

The evidence from India shows that (i) discussions that only look at “winners” in poor countries and “losers” in rich countries miss the point that the gains from trade are unequally distributed within both sets of countries; and (ii) context-specific factors, like worker mobility across sectors and geographic regions, are crucial to understand the impact of trade on incomes.

- Donaldson (2018) uses archival data from colonial India to estimate the impact of India’s vast railroad network. He finds railroads increased trade, and in doing so they increased real incomes (and reduced income volatility).5

- Porto (2006) looks at the distributional effects of Mercosur on Argentine families, and finds this regional trade agreement led to benefits across the entire income distribution. He finds the effect was progressive: poor households gained more than middle-income households, because prior to the reform, trade protection benefitted the rich disproportionately.6

- Trefler (2004) looks at the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement and finds there was a group who bore “adjustment costs” (displaced workers and struggling plants) and a group who enjoyed “long-run gains” (consumers and efficient plants). 7

From income to welfare: a closer look at the ‘expenditure channel’

The fact that trade negatively affects labor market opportunities for specific groups of people does not necessarily imply that trade has a negative aggregate effect on household welfare. This is because, while trade affects wages and employment, it also affects the prices of consumption goods. So households are affected both as consumers and as wage earners.

Most studies focus on the earnings channel, and try to approximate the impact of trade on welfare by looking at how much wages can buy, using as reference the changing prices of a fixed basket of goods.

This approach is problematic because it fails to consider welfare gains from increased product variety, and obscures complicated distributional issues such as the fact that poor and rich individuals consume different baskets so they benefit differently from changes in relative prices.8

Ideally, studies looking at the impact of trade on household welfare should rely on fine-grained data on prices, consumption and earnings. This is the approach followed in Atkin, Faber, and Gonzalez-Navarro (2018): “Retail globalization and household welfare: Evidence from Mexico”.9

Atkin and coauthors use a uniquely rich dataset from Mexico, and find that the arrival of global retail chains led to reductions in the incomes of traditional retail sector workers, but had little impact on average municipality-level incomes or employment; and led to lower costs of living for both rich and poor households.

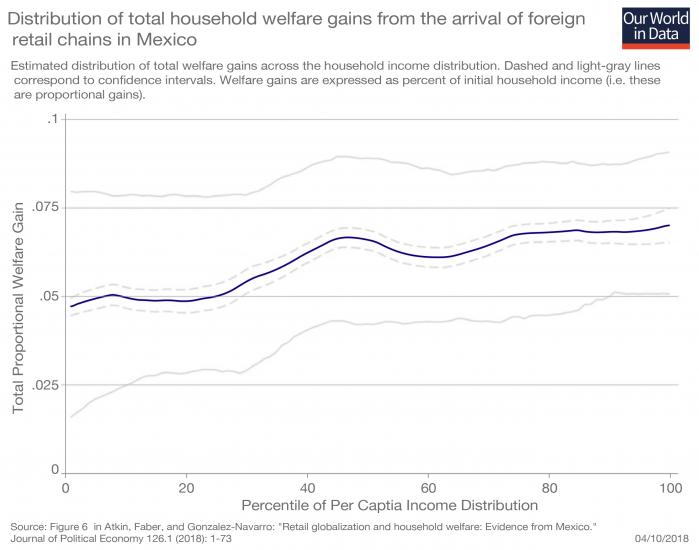

The chart here shows the estimated distribution of total welfare gains across the household income distribution (the light-gray lines correspond to confidence intervals). These are proportional gains, and are expressed as percent of initial household income.

As we can see, there is a net positive welfare effect across all income groups; but these improvements in welfare are regressive, in the sense that richer households gain proportionally more (about 7.5 percent gain compared to 5 percent).10

Evidence from other countries confirms this is not an isolated case – the expenditure channel really seems to be an important and understudied source of household welfare. Giuseppe Berlingieri, Holger Breinlich, Swati Dhingra, for example, investigate the consumer benefits from trade agreements implemented by the EU between 1993 and 2013; and they find that these trade agreements increased the quality of available products, which translated into a cumulative reduction in consumer prices equivalent to savings of €24 billion per year for EU consumers.11

Distribution of total household welfare gains from the arrival of foreign retail chains in Mexico – Atkin, Faber, and Gonzalez-Navarro (2018)

Wrapping up: Net welfare effects and implications

The available evidence shows that, for some groups of people, trade has a negative effect on wages and employment opportunities; and at the same time it has a large positive effect via lower consumer prices and increased availability of products.

Two points are worth emphasising.

For some households, the net effect is positive. But for some households that’s not the case. In particular, workers who lose their job can be affected for extended periods of time, so the positive effect via lower prices is not enough to compensate them for the reduction in earnings.

On the whole, if we aggregate changes in welfare across households, the net effect is usually positive. But this is hardly a consolation for those who are worse off.

This highlights a complex reality: There are aggregate gains from trade, but there are also real distributional concerns. Even if trade is not a major driver of income inequalities, it’s important to keep in mind that public policies, such as unemployment benefits and other safety-net programs, can and should help redistribute the gains from trade.