The future is vast – what does this mean for our own life?

If we manage to avoid a large catastrophe, we are living at the early beginnings of human history.

The text and title were last updated on August 10, 2022.

The point of this text is not to predict how many people will ever live. What I learned from writing this post is that our future is potentially very, very big.

If we keep each other safe – and protect ourselves from the risks that nature and we ourselves pose – we are only at the beginning of human history.

Our actions today impact those who will live in that vast future that is ahead of us.

- Our impact can be negative – for example when we degrade the environment that future generations will inherit from us, or when we develop technologies that create risks for them.

- But our impact can also be positive – by developing science that allows these future generations to live healthier lives, or by building a culture that enriches their lives in the way that our history enriches our lives.

The fact that our actions have an impact on the large number of people who will live after us should matter for how we think about our own lives. Those who ask themselves what they can do to act responsibly towards those who will live in the future call themselves 'longtermists'. Longtermism is the ethical view that we should act in ways that reduce the risks that endanger our future, and in ways that make the long-term future go well.1

Our past

Before we look ahead, let’s look back. How many came before us? How many humans have ever lived?

It is not possible to answer this question precisely, but demographers Toshiko Kaneda and Carl Haub have tackled the question using the historical knowledge that we do have.

There isn’t a particular moment in which humanity came into existence, as the transition from species to species is gradual. But if one wants to count all humans one has to make a decision about when the first humans lived. The two demographers used 200,000 years before today as this cutoff.2

The demographers estimate that in these 200,000 years about 109 billion people have lived and died.3

It is these 109 billion people we have to thank for the civilization that we live in. The languages we speak, the food we cook, the music we enjoy, the tools we use – what we know we learned from them. The houses we live in, the infrastructure we rely on, the grand achievements of architecture – much of what we see around us was built by them.

Our present

In 2022 7.95 billion of us are alive. Taken together with those who have died, about 117 billion humans have been born since the dawn of modern humankind.

This means that those of us who are alive now represent about 6.8% of all people who ever lived.

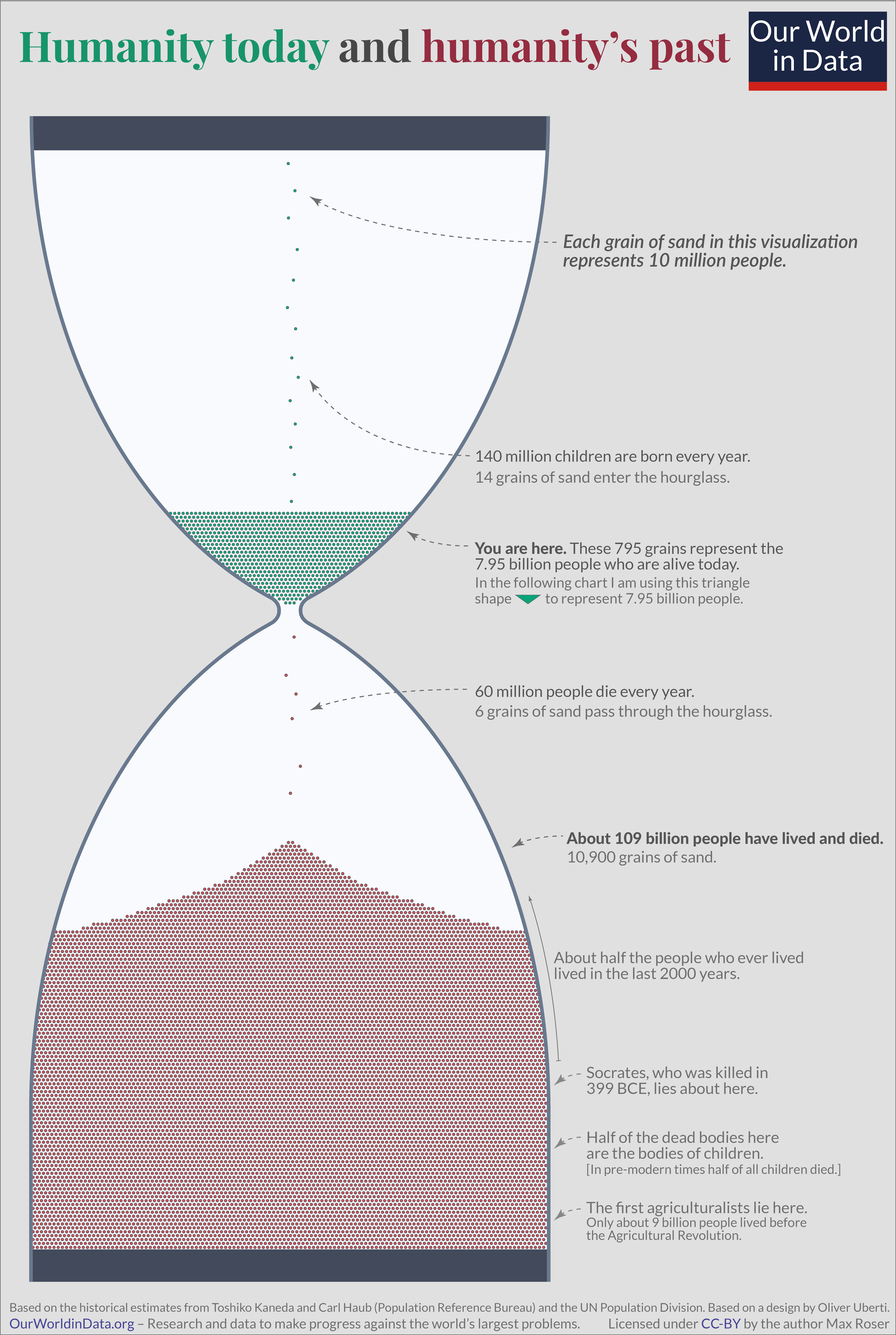

These numbers are hard to grasp. I tried to bring it into a visualization to put them into perspective.4

It’s a giant hourglass. But instead of measuring the passage of time, it measures the passage of people.

Each grain of sand here represents 10 million people: each year 140 million babies are born. So we add 14 grains of sand to the hourglass. Every year, 60 million people die; this means 6 grains pass through the hourglass and are added to the large number of people who have died.5

Our potential future

How many people will be born in the future?

We don’t know.

But we know one thing: The future is immense, and the universe will exist for trillions of years.

We can use this fact to get a sense of how many descendants we might have in that vast future ahead.

The number of future people depends on the size of the population at any point in time and how long each of them will live. But the most important factor will be how long humanity will exist.

Before we look at a range of very different potential futures, let’s start with a simple baseline.

We are mammals. One way to think about how long we might survive is to ask how long other mammals survive. It turns out that the lifespan of a typical mammalian species is about 1 million years.6 Let’s think about a future in which humanity exists for 1 million years: 200,000 years are already behind us, so there would be 800,000 years still ahead.

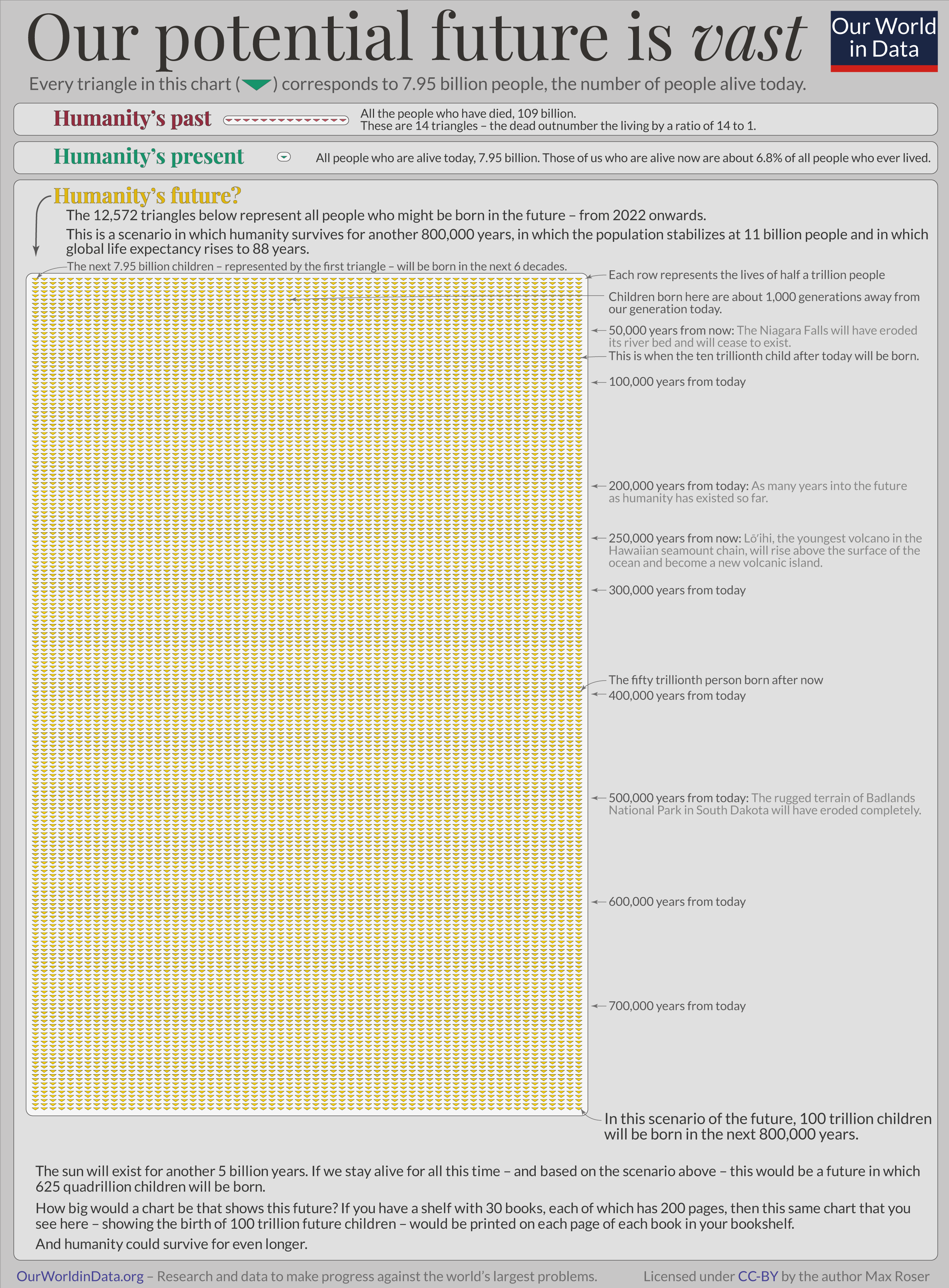

Let’s consider a scenario in which the population stabilizes at 11 billion people (based on the UN projections for the end of this century) and in which the average life length rises to 88 years.7

In such a future, there would be 100 trillion people alive over the next 800,000 years.

The chart visualizes this. Each triangle represents 7.95 billion people – it is the green triangle shape from the hourglass above and corresponds to the number of us alive today.

Each row represents the birth of half a trillion children. For 100 trillion births there are 200 rows.

If you disagree with the numbers I use in my scenario it is easy for you to see how different numbers would lead to different futures. Here are two examples:

- If you think the world population will stabilize at a level that’s 50% higher than in my calculation, then the number of future births will be 50% higher. The chart would be 50% wider. It would show the births of 150 trillion children.

- If you think the world population will have a size of just one billion people, then the chart would be only an eleventh as wide and would show 9.1 trillion births.8

The chart shows how many children might be born in the next 800,000 years, a future in which humans survive for as long as a typical mammalian species.

But, of course, humanity is anything but “a typical mammalian species.”

One thing that sets us apart is that we now – and this is a recent development – have the power to destroy ourselves. Since the development of nuclear weapons, it is in our power to kill all of us who are alive and cause the end of human history.

But we are also different from all other animals in that we have the possibility to protect ourselves, even against the most extreme risks. The poor dinosaurs had no defense against the asteroid that wiped them out. We do. We already have effective and well-funded asteroid-monitoring systems and, in case it becomes necessary, we might be able to deploy technology that protects us from an incoming asteroid. The development of powerful technology gives us the chance to survive for much longer than a typical mammalian species.

Our planet might remain habitable for roughly a billion years.9 If we survive as long as the Earth stays habitable, and based on the scenario above, this would be a future in which 125 quadrillion children will be born. A quadrillion is a 1 followed by 15 zeros: 1,000,000,000,000,000.

A billion years is a thousand times longer than the million years depicted in this chart. Even very slow-moving changes will entirely transform our planet over such a long stretch of time: a billion years is a timespan in which the world will go through several supercontinent cycles – the world’s continents will collide and drift apart repeatedly; new mountain ranges will form and then erode, the oceans we are familiar with will disappear and new ones open up.

But if we protect ourselves well and find homes beyond Earth, the future could be much larger still.

The sun will exist for another 5 billion years.10 If we stay alive for all this time, and based on the scenario above, this would be a future in which 625 quadrillion children will be born.

How can we imagine a number as large as 625 quadrillions? We can get back to our sand metaphor from the first chart.

We can imagine today’s world population as a patch of sand on a beach. It’s a tiny patch of sand that barely qualifies as a beach, just large enough for a single person to sit down. One square meter.

If the current world population was represented by a tiny beach of one square meter, then 625 quadrillion people would make up a beach that is 17 meters wide and 4600 kilometers long. A beach that stretches all across the USA, from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast.11

And humans could survive for even longer.

What this future might look like is hard to imagine. Just as it was hard to imagine, even quite recently, what today might look like. “This present moment used to be the unimaginable future,” as Stewart Brand put it.

Our responsibility is vast

A catastrophe that ends human history would destroy the vast future that humanity would otherwise have.

And it would be horrific for those who will be alive at that time.

The people who live then will be just as real as you or me. They will exist, they just don’t exist yet. They will feel the sun on their skin and they will enjoy a swim in the sea. They will have the same hopes, they will feel the same pain.

‘Longtermism’ is the idea that people who live in the future matter morally just as much as those of us who are alive today.12 When we ask ourselves what we should do to make the world a better place, a longtermist does not only consider what we can do to help those around us right now, but also what we can do for those who come after us. The main point of this text – that humanity’s potential future is vast – matters greatly to longtermists. The key moral question of longtermism is ‘what can we do to improve the world’s long-term prospects?’.

In some ways, many of us are already longtermists. The responsibility we have for future generations is why so many work to reduce the risks from climate change and environmental destruction.

But in other ways, we pay only little attention to future risks. In the same way that we work to reduce the risks from climate change, we should pay attention to a wider range of potentially even larger risks and reduce them.

I am definitely frightened of these catastrophic and existential risks.13 In addition to nuclear weapons, there are two other major risks that worry me greatly: Pandemics, especially from engineered pathogens, and artificial intelligence technology. These technologies could lead to large catastrophes, either by someone using them as weapons or even unintentionally as a consequence of accidents.14

Large risks are not only a problem in the future — they are a reality now

We don’t have to think about people who live billions of years in the future to see our responsibilities. The majority of today’s children can expect to see the next century. Some of our grandchildren might live long enough to see the 23rd century. A catastrophe in the next decades would be horrific for people very close to us.

The focus of this text is the long-term future, but this shouldn’t give the impression that the risks we are facing are confined to the future. Several large risks that could lead to unprecedented disasters are already with us now. The use of the nuclear weapons that exist at this moment would kill millions immediately and billions in the ‘nuclear winter’ that follows (see my post on nuclear weapons). Not enough people have registered how the situation we are in has changed. AI capabilities and biotechnology have developed rapidly and are no longer science fiction; they are posing risks to those of us who are alive today.15

Similarly, this text focuses mostly on the loss of human lives, but there would be other losses too: nuclear war would devastate nature and the world’s wildlife; existential catastrophes would destroy our culture, our civilization.

The point is that even if we only consider the impact of these risks on the present generation and only consider the potential loss of lives, they’re among the most pressing issues of our time. This is much more the case if we consider their impact beyond mortality and their impact on future generations.

The reduction of existential risks is one of the most important tasks of our time, yet it is extremely neglected

The current pandemic has made it clear how badly the world has neglected pandemic preparedness. This illustrates a more general point. By reducing the risk of the catastrophes which would endanger our entire future – for example, the very worst possible pandemics – we would also reduce the risk of smaller, yet still terrible, disasters, such as COVID-19.

As a society, we spend only little attention, money, and effort on the risks that imperil our future. Only very few are even thinking about these risks, when in fact these are problems that should be central to our culture. The unprecedented power of today’s technology requires unprecedented responsibility.

Technological development made the high living standards of our time possible. I believe that a considerable share of the fruits of this growth should be spent on reducing the risks and negative consequences of particular technologies.

More researchers should be able to study these risks and how we can reduce them. I would love to see more artists who convey the importance of the vast future in their work. And crucially I think it needs competent political work. I imagine that one day countries will have ministries for the reduction of catastrophic and existential risks and some of the world’s most important institutions will be dedicated to the far-sighted work that protects humanity.

It will be too late to react once the worst has happened. This means we have to be proactive; we have to see the threats now.

The current situation in which these risks are hardly receiving any attention is frightening and depressing. But it is also a large opportunity. Because these risks are so very neglected, a career dedicated to the reduction of these risks is likely among the best opportunities that you have if you want to make the world a better place.

Our opportunities are vast too

So far I’ve only spoken about the risks that we face. But our large future means that there are large opportunities too.

Problems are solvable. This is for me the most important insight that I learned from writing Our World in Data over the last decade.

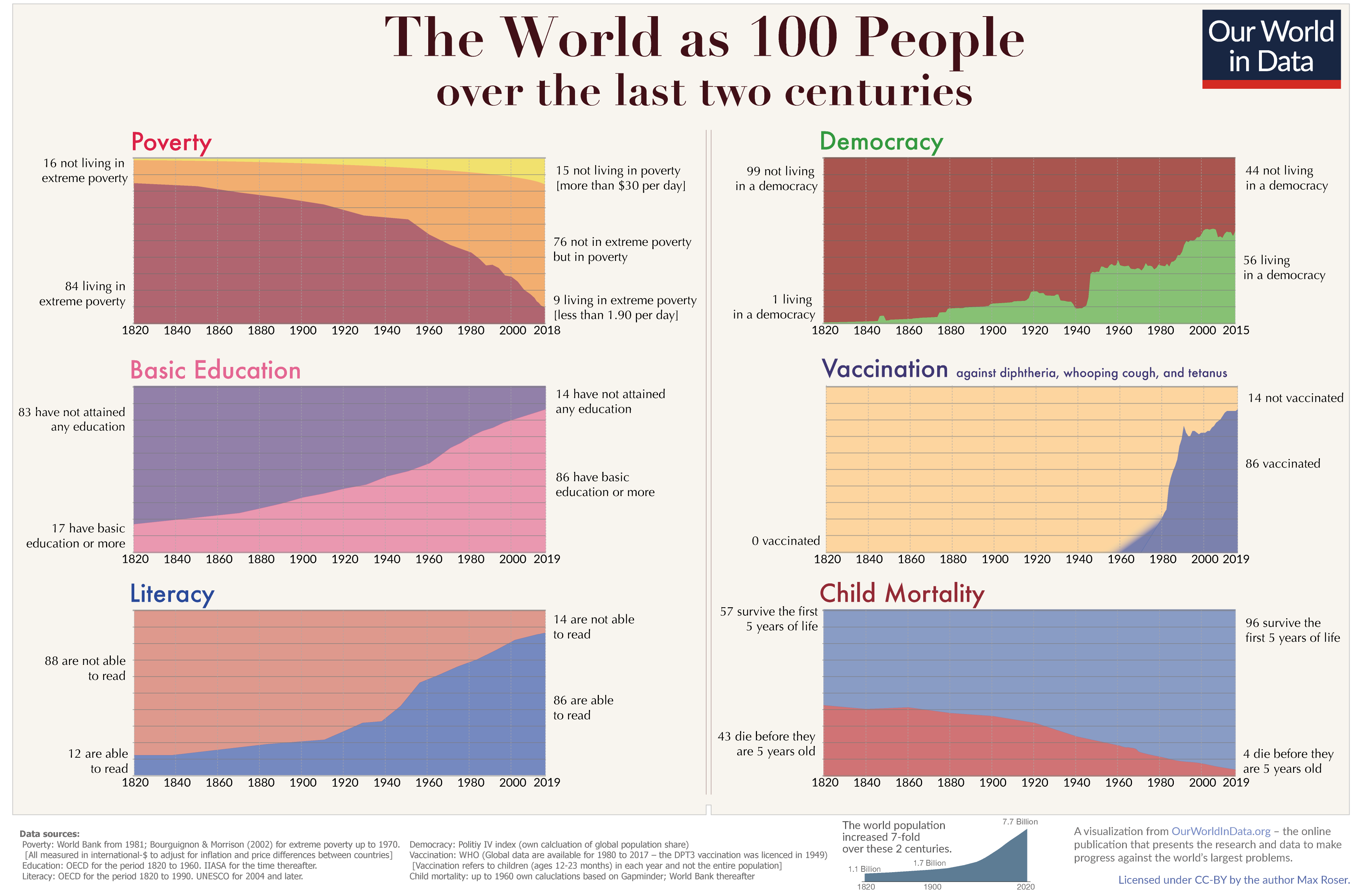

Compared to the vast future ahead, the two centuries shown in this chart here are only a brief episode of human history. But even in such a short period, we have made substantial progress against many large problems.

Given enough time we can end the horrors of today. Poverty is not inevitable; we can achieve a future where people are not suffering from scarcity. Diseases that are incurable today might be curable in just a few generations; we already have an amazing track record in improving people’s health. And we can achieve a world in which we stop damaging the environment and achieve a future in which the world’s wildlife flourishes.

Our children and grandchildren can continue the progress we are making, and they may create art and build a society more beautiful than we can even imagine.

Conclusion

The point of this text was to see that the future is big. If we keep each other safe the huge majority of humans who will ever live will live in the future.

And this requires us to be more careful and considerate than we currently are. Just as we look back on the heroes who achieved what we enjoy today, those who come after us will remember what we did for them. We will be the ancestors of a very large number of people. Let’s make sure we are good ancestors.

For this, we need to take the risks we are facing more seriously. The risks we are already facing are high. Giving this reality the attention it deserves is the first step, and only very few have taken it. The next step will be to identify what we can do to reduce these risks and then set about doing that.

Let’s also see the opportunity that we have. Those who came before us left us a much better world; we can do the same for the many who come after us.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Anders Sandberg, Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, and Will MacAskill for their very helpful comments on this essay.

Endnotes

On longtermism see William MacAskill (2022) – ‘What We Owe The Future’ and literature referenced in the later sections and at the end of this text.

One could also choose a much earlier point in time. Recent research from the Jebel Irhoud site in modern-day Morocco suggests that it could be as early as 315,000 BCE. See: Ewan Callaway (2017) – ‘Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history’. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114.

But I should also note that for the estimates of the total number of total people it does not matter very substantially. This is because the population size of our species was very low in those early days, and at several times our species was close to extinction.

The majority of them lived very short lives: about one in two children died in the past. When conditions are so very poor and children die so quickly then the birth rate has to be extremely high to keep humanity alive; Kaneda and Haub assume a birth rate of 80 births per 1000 people per year for most of humanity’s history (up to the year 1 CE). That is a rate of births that is about 8-times higher than in a typical high-income country and more than twice as high as in the poorest countries today (see the map). The past was a very different place.

As noted in this visualization, this is an updated adaptation of a 2013 visualization by Oliver Uberti. You find it on his website. I also recommend having a look at his books, which he co-authored with James Cheshire; they are beautiful data visualization books.

The cited numbers are from the UN’s demographic projection published in the year 2019 for the year 2022 (see here). With the ongoing COVID pandemic the number of deaths is likely going to be higher than expected. You can track ‘excess deaths’ during the pandemic here. In 2021 excess deaths were possibly in the range of 10 million, if the same should be true in 2022 the chart should show 7 instead of 6 grains passing through the hourglass.

All references and calculations are in the Appendix below.

To not clutter this post with footnotes, I have put all my sources and all calculations in a long appendix below this post.

1 billion is one-eleventh of 11 billion. And 9.1 trillion is one-eleventh of 100 trillion.

All references and all calculations are in the Appendix below.

All sources and calculations are in the Appendix.

Here is the calculation:

The ratio between 625 quadrillions and the current world population is 78.6 million to one.

[625,000,000,000,000,000 / 7,953,952,577 = 78,577,285]

78,577,285 meter are 78,577 kilometer

Making the beach 17 meters wide means it is 4,622km long (78,577/17).

These are 2872 miles.

For an introduction to longtermism read Benjamin Todd (2017) – Why our impact in millions of years could be what most matters.

Existential risks are those that can cause human extinction or can permanently curtail humanity's potential so that survivors would not have sufficient means to recover.

Catastrophic risks are similar in that they are large global risks that could kill billions of people, but they retain the possibility of recovery.

See for example Future of Life Institute Existential Risks.

AI technology could have the power to transform our world in undesirable ways, either unintentionally or intentionally as a weapon. On the risks – and opportunities of artificial intelligence – I recommend Brian Christian’s book ‘The Alignment Problem – Machine Learning and Human Values’.

On pandemics – and Global Catastrophic Biological Risks more broadly – I recommend the relatively brief online text ‘Reducing global catastrophic biological risks’ written by Gregory Lewis for 80,000 Hours. In the same publication, you also find a discussion of the risks from extreme climate change: Climate change authored by Benjamin Hilton.

I consider the four risks that I mentioned – nuclear weapons, climate change, and especially pandemics and AI – to be the most dangerous known risks, but unfortunately these are not the only risks. There are several other risks that could potentially lead to large catastrophes. For a broader discussion of existential risks I recommend The Precipice by Toby Ord.

See the references in the footnote before the previous one.

“Isaac Asimov (1979) – A Choice of Catastrophes: The Disasters that Threaten Our World.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2022) - "The future is vast – what does this mean for our own life?". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://staging-owid.netlify.app/the-future-is-vast' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-the-future-is-vast,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {The future is vast – what does this mean for our own life?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://staging-owid.netlify.app/the-future-is-vast}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.