Stunting is one of the leading measures used to assess childhood malnutrition. It indicates that a child has failed to reach their growth potential as a result of disease, poor health and malnutrition.1

A child is defined as ‘stunted’ if they are too short for their age. This indicates that their growth and development have been hindered.

Stunting is not just an issue during childhood. It affects both physical and cognitive development – impacts that can persist throughout someone’s life. There is some evidence to suggest that ‘catch-up growth’ is possible: that it is possible to reverse some of these impacts if environmental conditions significantly improve. But this is not always the case.

Stunting is measured based on a child’s height relative to their age.

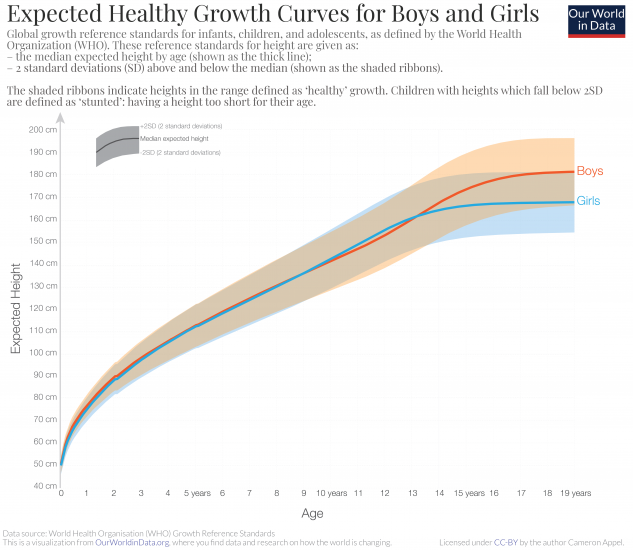

The World Health Organization (WHO) sets out global growth curves – these show the expected trajectory of a child’s growth from birth through to adulthood. Of course, we would not expect everyone to be exactly the same height – there is a range of factors, such as genetics, which influence our height and are not a reflection of poor health or malnutrition. These growth curves therefore span a range of heights.

We see these growth curves for boys and girls in the chart. The median growth curve is shown by the thick line. The ribbons around this median show the ‘acceptable’ range. This range is two standard deviations above and below the median.

A child whose height falls below the bottom of the ribbon – that is, two standard deviations below their expected height for their age – is defined as ‘stunted’.

In a population, the prevalence of stunting is defined as the share of children under five years old that fall two standard deviations below the expected height for their age.

To estimate the prevalence of stunting, researchers draw on household and demographic surveys, which include measurements of childhood growth, alongside official health data from governments that monitor child development.

Stunting can occur throughout childhood, but is largely determined by a child’s “first 1,000 days”. This stretches from the period just before conception (meaning the nutritional status of mothers is very important) through to the child’s second birthday. This is when a child experiences its most rapid phase of growth and development.

Stunting occurs when a child does not have sufficient nutrition to grow and develop. This can be caused by a poor diet alone, but is often exacerbated by disease and poor health.

When a child is fighting poor health or disease, its nutritional requirements are often higher – it needs more energy and nutrients to not only grow, but to also fight infection. The absorption of nutrients might also be impacted. For example, if it experiences repeated bouts of diarrheal diseases – which are common in children – its ability to retain nutrients will be severely impacted.

Therefore, to prevent stunting we must ensure mothers have good nutrition and health prior to, and during, pregnancy; a child has access to a sufficient and nutritious diet; has access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene facilities to prevent infection; and has adequate treatment to recover quickly from disease and poor health.