Diarrhea is the third leading cause of child mortality – it claimed more than half a million children in 2017. Rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrhea in children – it is estimated that between one-quarter and one-third of all child deaths from diarrhea are the result of rotavirus infection.

Countries which have introduced vaccines against rotavirus have seen significant reductions in rotavirus-related cases of diarrhea. Improved coverage and better vaccine efficacy in low-income countries could save even more lives.

Rotavirus is the leading cause of childhood diarrhea

Rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrheal disease in children globally. It’s estimated that between one-quarter and one-third of all child deaths from diarrhea are the result of rotavirus infection.1

The Global Burden of Disease study estimated that rotavirus was the cause of 128,500 deaths and was responsible for an estimated 258 million cases of infectious diarrhea among children under-5 in 2016.2

The map shows the global distribution of rotavirus-related child deaths. As we can see, the highest mortality rates occur in the Sub-Saharan region. In terms of total numbers, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and India have the highest total number of rotavirus-related deaths.

Childhood wasting, access to clean water and unsafe sanitation are the major risk factors, associated with 84% of all deaths from diarrheal disease in children.3

While reducing these risk factors can help to avoid a large number of rotavirus cases, it is not sufficient to prevent all infections. However, we do have an effective intervention against the virus: the rotavirus vaccine.

Rotavirus vaccines

The first widely-used rotavirus vaccine was approved in the United States in 2006. Today, there are four oral rotavirus vaccines recommended for use by the World Health Organisation (WHO): Rotarix, RotaTeq, RotaSiil, and Rotavac.4

Rotarix and RotaTeq are the most widely used and both have shown good efficacy against rotavirus infections in clinical trials.56

Since the use of rotavirus vaccines have been approved, they have had a notable impact on the reduction of rotavirus-related deaths. According to a study published in 2018, the use of rotavirus vaccines prevented approximately 28,900 child deaths globally in 2016. However, as the chart shows, full vaccine use – that is a 100% coverage globally – could have prevented an additional 83,200 deaths.7 This means that, even at the current rates of efficacy, 53% of all deaths in children under-5 from rotavirus in 2016 could have been avoided by full vaccine coverage.

In addition to saving lives, the rotavirus vaccine also reduces the burden on healthcare systems. Between 2008 and 2016 the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine has reduced the number of diarrhea-related hospital admissions on average by 40%.8

If there is so much scope for saving more children’s lives, what is the reason that these children are still dying?

There are two key barriers to achieving the full potential of the rotavirus vaccine: immunization rates, and the efficacy of the vaccine in specific regions.

According to the WHO, by the end of 2018, 101 countries were using the rotavirus vaccine. The major drivers for the introduction of the vaccine are the burden of diarrheal diseases, the availability of funding, and a favourable political climate for vaccines.9

The vaccine is only given to children – it’s recommended that the vaccination should be initiated 15 weeks after birth and finished by the 32nd week. However, the global coverage is still very low: it is estimated that just 35% of under one-year-olds were vaccinated in 2018.10

The map shows the WHO estimates on the share of one-year olds who received the full recommended dosage of the vaccine (two immunizations for Rotarix vaccine or three immunizations for RotaTeq vaccine). For many countries where data coverage is low, it’s expected that the share of infants receiving the vaccine is very low. Some countries however did see rapid increases in rates of immunization. In a period of only a few years countries including Sudan, Malawi and Gambia have increased immunisation rates from below 10% to 80-95% – click on the country to see the change over time.

Since most rotavirus cases occur in Sub-Saharan Africa where mortality from rotavirus infection is also the highest, it is essential to increase and maintain high immunisation coverage in this region. However, in addition to delivering the vaccine for those who need it, we also need to work on improving its efficacy.

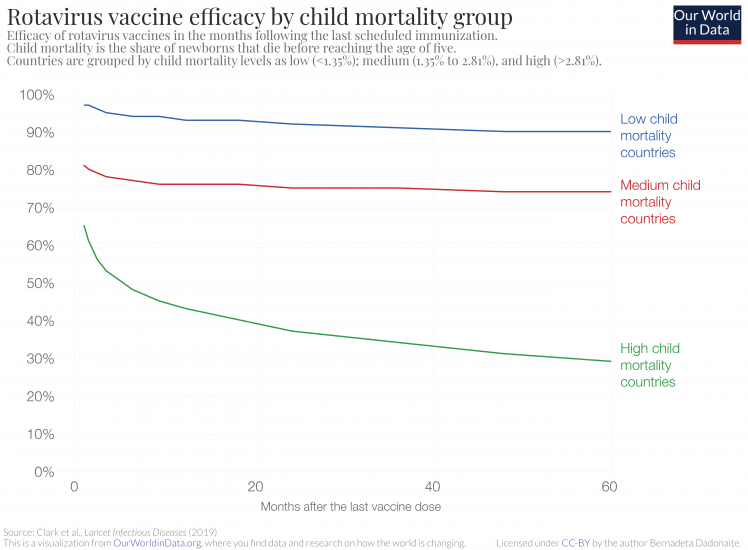

Vaccine efficacy for the rotavirus vaccine is defined as the percentage reduction of the rate of diarrhea incidences in vaccinated versus unvaccinated groups of children. It is well established that the efficacy of the rotavirus vaccine is not the same across all countries — in countries with high child mortality rates the vaccine shows much lower efficacy.11

The chart is from a recent study by Clark et al., which looked at how the efficacy of live oral rotavirus vaccines changes in different countries following vaccination. The chart shows that in countries with high child mortality rates, not only is the immediate vaccine efficacy lower – 98% in low child mortality countries versus 66% in high child mortality countries – but also the vaccine efficacy decreases faster in high child mortality countries over time.12

Five years after vaccination, the rotavirus vaccine reduces the chances of getting diarrhea by 90% in low child mortality countries and only by 30% in high mortality countries.

The table shows how good the rotavirus vaccine is at preventing severe diarrhea and reducing hospitalization due to diarrhea in children under-5 in different regions.13

In high-income countries, rotavirus vaccination has been shown to reduce the cases of severe rotavirus diarrhea by 91% and hospitalization by 94%. In Eastern Asia and Latin America, the effectiveness rates are lower but still high – preventing 88% and 80% of severe diarrhea cases, respectively. However, effectiveness in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa is significantly lower, only reducing severe diarrhea in around half of the cases.

The reasons for different responses to the vaccine are not entirely clear.14 15

It is likely that the gut responses to the oral rotavirus vaccines in children in lower-income countries are different. This may be due to a variety of causes, including micronutrient deficiencies, pre-vaccination exposure to certain pathogens, and the presence of chronic conditions such as malaria or HIV. Overall, the poor gut response to the live vaccine means the efficacy of the vaccine is reduced. Taking all of the above mentioned points into account, there are several interventions that could increase the benefits of the rotavirus vaccine even further. In addition to increasing the vaccine coverage, improving nutritional health (of both infants and mothers) and improving hygiene and sanitation conditions (to lower the prevalence of damaging pathogens) could have positive effects on the vaccine’s efficacy.

We are still at quite an early stage of the rotavirus vaccine use. Although the vaccine has brought huge benefits already, it could go even further. Improving vaccination coverage, particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia is key to continued reduction of childhood deaths from diarrhea. Even at moderate levels of vaccine efficacy, a significant number of additional additional child deaths could be prevented every year. The bar chart above that shows the number of preventable deaths illustrates the potential for extended vaccine coverage to save many more lives. And this is already taking into account the regional differences in the vaccine’s effectiveness.

In addition to increased coverage, improving the effectiveness of the vaccine would go even further in tackling one of the leading causes of death.

| Outcome | Region | Vaccine effectivness |

|---|---|---|

| Severe rotavirus diarrhea | Developed | 91% |

| Eastern Asia and Southeast Asia | 88% | |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 80% | |

| Southern Asia | 50% | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46% | |

| Hospitalization due to rotavirus infection | Developed | 94% |

| Eastern Asia and Southeast Asia | 94% | |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 84% | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 58% |

Other high-impact interventions

While rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrhea in children and therefore, rotavirus vaccine can save the lives of many children, it is not the only cause of diarrhea. To prevent deaths from other diarrheal diarrheal pathogens we need additional interventions and treatments.

Deaths from other diarrheal pathogens, such as cholera or shigella, could be avoided by antibiotics or vaccines, where they are available. But preventions that limit the risks of exposure to diarrheal pathogens in the first place are the key to saving the most lives. Unsafe water and unsafe sanitation contributed to 72% and 56% of the under-5 deaths from diarrheal diseases in 2016. Children who are undernourished, are less likely to survive a diarrheal episode. Consequently, childhood wasting (having a weight too low for their height) is the leading risk factor for diarrheal mortality in children, contributing to an estimated 80% of under-5 deaths from diarrheal diseases in 2016.16

Clearly, eliminating risk factors associated with diarrheal diseases should be on our priority list.

One of the most cost-effective ways to treat most cases of diarrhea, including those due to rotavirus infection, is not a highly sophisticated drug or vaccine but a simple water, salt and sugar solution: oral rehydration therapy (ORT). ORT can be used to prevent deaths from diarrhea originating from any cause, and has already saved the lives of tens of millions of children since its introduction in the 1970s. We will cover the successes and potential of ORT in an upcoming post.