After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, West German families that had relatives in East Germany saw an increase in their income, and this growth in incomes was significantly higher than that of comparable West German families without such family ties to the East.

Why did this happen? Are personal and family ties really so important to our economic outcomes that they result in systematic differences in income growth?

Researchers have studied this question and have found empirical support for the idea that social connections do, indeed, have large effects on economic outcomes.

Measuring the impact of personal relations on economic outcomes is difficult. This is because these two aspects of our life are often closely intertwined – social ties facilitate economic interactions, but at the same time people with whom we interact for economic reasons end up becoming acquaintances or even friends.

To overcome this difficulty, the economists Konrad Burchardi and Tarek Hassan studied a historical event that suddenly opened up new economic interactions, where previously only non-economic social connections were possible: The fall of the Berlin Wall.1

For decades private economic exchange between East and West Germany was virtually impossible, but at the same time people on both sides maintained social ties for non-economic reasons. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, trade and collaboration between the two Germanies suddenly became feasible. Burchardi and Hassan studied the impact that this sudden change had on household incomes.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 there was growth in incomes across Germany as a whole; but the interesting finding from Burchardi and Hassan is that income growth for households in West Germany who had ties to at least one relative in the East was much higher – six percentage points higher – than that of comparable households without such ties.

Burchardi and Hassan argue that West German households that had ties to East Germany had a comparative advantage in seizing the new economic opportunities in the East. Having personal relationships with East Germans gave them access to valuable economic information – information regarding local demand conditions, and about the quality of East German assets that were offered to investors.

These gains from social connections actually added up at the regional level. West German regions that had a higher concentration of households with social ties to the East, enjoyed substantially higher growth in incomes in the early 1990s. A one standard deviation rise in the share of households with social ties to East Germany in 1989 was associated with a 4.6 percentage point rise in income per capita over six years.

The unique situation of the German reunification shows that social ties that are initially unrelated to economic interests can become important for economic success.

The key mechanism is that personal connections allow us to seize new economic opportunities. This may sound abstract, but in fact most of us have experienced this in our own lives. Perhaps the best example is job searching: personal contacts and connections are one of the most common ways for people to find a job.

In the book The Human Network, the economist Matthew Jackson draws on decades of research to help explain how social connections affect power, beliefs and behaviors. With regard to job networks and social capital, he writes: “If you have ever struggled to find a job, you are not alone. Without well-connected friends or family it is hard to make it in any industry […]. Finding a job without having some personal connection to someone already employed at a firm is more the exception than the rule.” 2

Our interactive chart here shows evidence for Jackson’s claim using data from European countries.

The chart shows the distribution of job search methods by country. Data for Spain is shown by default, but you can explore data for different countries using the option ‘Change country’.

In Spain, 84% of the unemployed rely on contacts – friends, relatives, trade unions – to find a job. It is the most common job-search method. Direct applications and ads rank below, on places two and three.

If you plot the same data for other countries you’ll see that personal contacts are a very important job-search method everywhere in Europe, but there is some variation across countries. At the lowest end of the spectrum, in Belgium, about 38% of people rely on contacts to find a job; at the other end, in Greece and Latvia, 90% of job seekers rely on this method.

(NB. This interactive map shows the same data, but focusing specifically on the proportion of job seekers relying on contacts for job search across Europe.)

Friends and relatives remain a popular method for finding a job, even in the age of digital job search platforms

The chart showing job search methods across Europe relies on data from the European Labor Force Survey, 2006-2008. We have not found more recent data that allows cross-country comparisons, but surveys from individual high-income countries show that this remains relevant today, even after the expansion of online job search engines, and the rise of social media platforms.

In the US, data from the Pew Research Center shows that the internet is the most important resource for job search, but 66% of survey respondents still say they relied on connections with close friends or family in their most recent search for a job.

These two methods are of course not mutually exclusive, and the boundaries between ‘internet’ and ‘personal contact’ are becoming less clear as job search platforms become more integrated with social media.

Personal relations can also provide information and social collateral that can be valuable for economic interactions across national borders.

The political scientist Anna Lee Saxenian analyzed the biographies of Chinese and Indian engineers who migrated to California in the 1970s. She found that as these skilled immigrants excelled in their personal careers, they started leveraging their social ties to relatives and friends in their home regions. This allowed them to outsource important operations for a large fraction of Silicon Valley firms.3

Saxenian argues that by connecting Silicon Valley firms to low-cost, high-quality labor in India and China, they became instrumental for the success of Silicon Valley and crucial in the emergence of their home regions as major hubs of the global IT services industry.

In some situations personal connections may facilitate economic transactions for one person (or group of people) at the expense of another one. This is what many people have in mind when they think about job referrals. If there is only one job vacancy, giving the job to a friend means not giving the job to someone else. If social connections become a vehicle for favouritism, this can lead to inefficiencies.

In many contexts, however, the opposite is true. Social connections often have a net-positive effect on aggregate economic outcomes because much of the impact of social connections on economic transactions is not zero-sum – for example, when social connections reduce information frictions and allow people to learn from each other. As we discuss in a companion post, there is empirical evidence showing these knowledge spillovers are substantial.

The concentration of firms and workers in ‘industry hubs’ is partly explained by the fact that social connections create economic externalities: Agglomeration leads to denser social connections, and this has positive spillover effects on productivity.

Again the fall of the Berlin Wall offers clear evidence of this.

When Berlin was split, economic activity in West Berlin shifted away from the historic business district, known as ‘Mitte’. As a consequence property prices there fell relative to the new economic areas that emerged further away from the Wall.

When the Wall came down the distribution of economic activity within the city changed quickly once again: The old business district began to re-emerge and economic activity shifted back to the historic center. This is the conclusion of a careful econometric study, published by Gabriel Ahlfeldt, Stephen Redding, Daniel Sturm and Nikolaus Wolf in the journal Econometrica.4

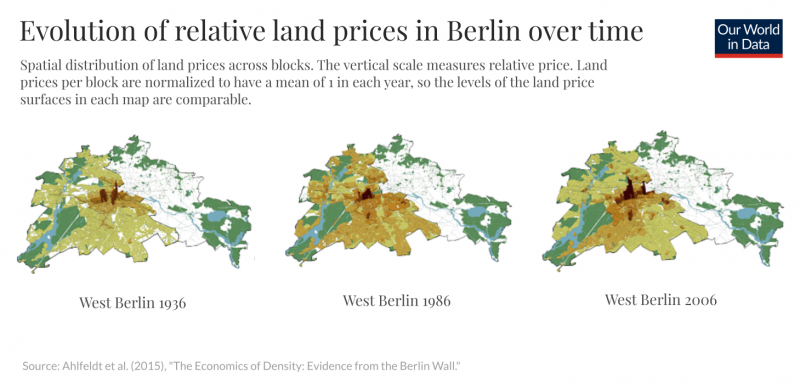

The three maps show the evolution of land prices in Berlin. These maps, from Ahlfeldt and co-authors, illustrate graphically the impact that the Wall had on the geography of economic activity. The vertical scale measures relative land prices; this means higher elevation, highlighted with darker shades, denotes higher prices.5

The map on the left shows that in 1936 there are two areas with very high land values in West Berlin and both are close to the center (they are both part of a concentric ring around the pre-war central business district, located in the middle).

In 1986, we see smaller peak values; in fact, we see that the pre-war peak closest to the Wall is entirely eliminated following division, as this area ceased to be an important center of commercial and retail activity.

Finally, in 2006, we see again higher peaks; and we see that the area closest to the Wall is reemerging as a center of high land values.

This evolution is a great example of the economics of density: The areas in West Berlin close to the old central business district became less productive during the division but regained their productivity and attractiveness again soon after reunification.

Knowledge, public resources, and opportunities for trade and collaboration that had been inaccessible for decades, suddenly became available after the fall of the Wall.6

Social connections matter hugely for economic outcomes. Personal relations, even those that we maintain for non-economic reasons, often give us access to information and provide us with social collateral for economic transactions – from buying a house to getting a job.

This can have positive consequences that extend beyond the individuals directly involved in the transactions. When personal and professional ties facilitate the exchange of information and knowledge, this can bring benefits to society as a whole. The implication from this is that social connections are not only important because they affect our emotional well-being, but also because, as we show here, they affect our material well-being too.