Malaria: One of the leading causes of child deaths, but progress is possible and you can contribute to it

We do not have to live in a world in which 1320 children die from a preventable disease every day.

This article draws on data and research discussed in our entry on Malaria.

Malaria is a disease that is transmitted by infected mosquitoes. The bite of an infected Anopheles mosquito transmits a parasite that enters the victim’s blood stream and travels into the person’s liver where the parasite reproduces. The parasite, called plasmodium, causes a high fever that involves shaking chills and pain. In the worst cases malaria leads to coma and death.

The World Health Organization estimates that 241 million people contract the disease every year.1 Only a small fraction of malaria victims die from it, but those who die are the very weakest – about three out of four malaria victims are children.2 Malaria is one of the leading causes of child mortality; it kills about half a million children every year.3 That’s 1320 dead children on any average day.

How can the world make progress against malaria?

In the history of health, the most important progress is often made in the prevention – rather than the treatment – of disease. For infectious diseases, prevention means interrupting its transmission.

Humanity’s most ingenious way of preventing infections is to achieve immunization through vaccines. The work on malaria vaccines goes back many decades, but unfortunately these vaccines have not been as successful as the vaccines against other diseases.4

There is however the hope that this will change. The mRNA technology – spurred by the COVID pandemic – seems promising also for the prospect of a vaccine against malaria. But it will certainly still take some time until a highly efficacious malaria vaccine is widely available.

In the meantime the world has to protect itself from malaria in other ways. This is something the world has been getting increasingly successful at.

Malaria was common across half the world – since then it has been eliminated in many regions

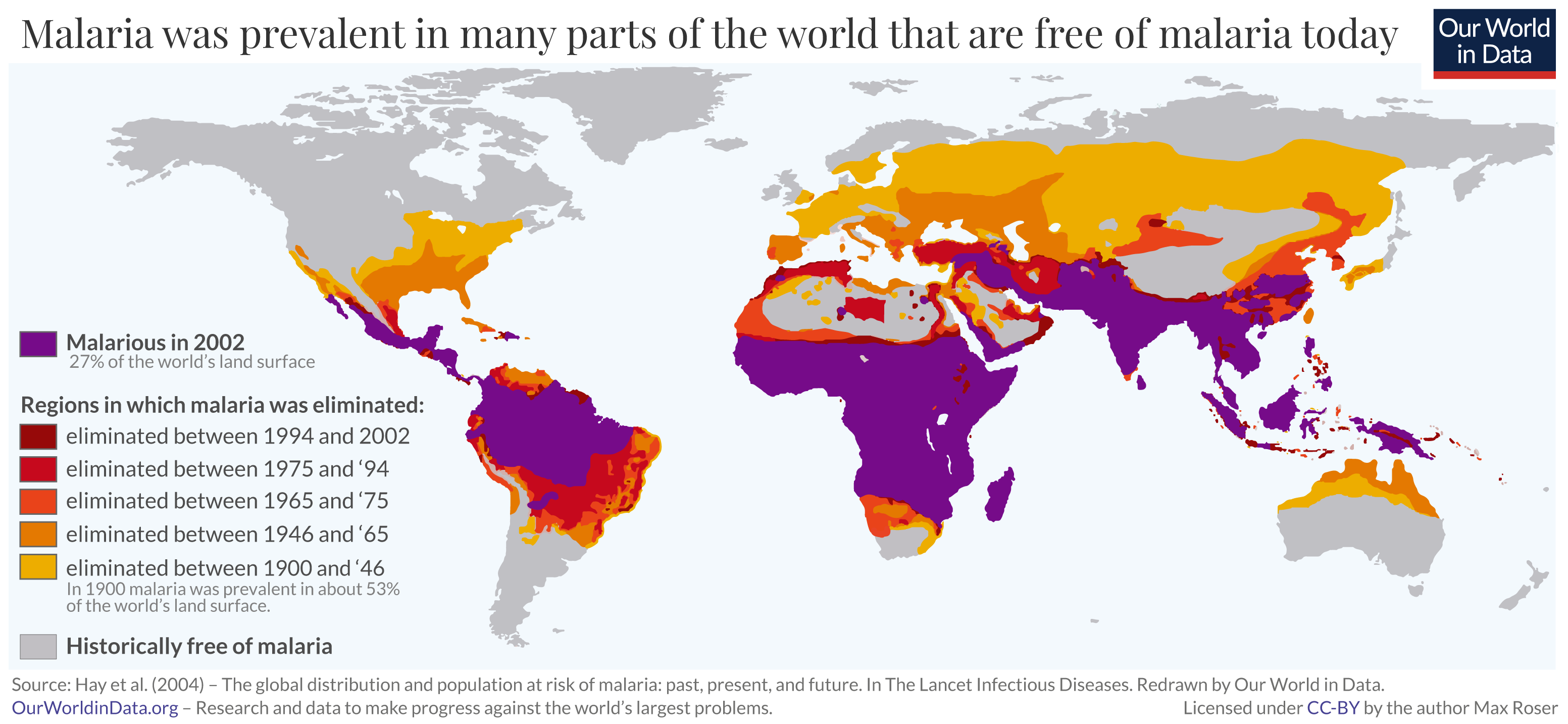

One line of humanity’s attack is to progressively reduce the area where malaria is prevalent.

Malaria is not a tropical disease. Rather, it is a disease that was eliminated everywhere but the tropics. Historically, malaria was prevalent in Europe and North America – Oliver Cromwell contracted the disease in Ireland, Friedrich Schiller in Mannheim, and Abraham Lincoln in Illinois.5

The map shows that in modern times the disease has been eliminated not only there, but also in East Asia and Australia and in many parts of the Caribbean, South America, and Africa. Researchers estimate that historically – and up to around the year 1900 – our ancestors were at risk from malaria across about half of the world’s land surface. Since then the area where humans are at risk of malaria contracted to a quarter.6

This was achieved through the use of insecticides, the drainage of swampland, and better housing conditions. Economic growth was crucial for these developments so that the disease is today mostly prevalent in the world’s poorest regions.

The often-repeated claim that malaria killed half of all humans who ever lived is very likely an overstatement, but it is certainly the case that the mosquito-borne fever was one of the most common causes of death in human history.7 In the last few generations humanity gained ground in this long-lasting battle against the disease. The WHO reports that the global mortality rate has declined by 90% in the 20th century.8

→ More detail in my text Malaria was common across half the world – since then it has been eliminated in many regions

Net Results: how the world is achieving progress where malaria is still prevalent

Economic development is a slow process. Are there opportunities to protect people from malaria right now?

Yes. A surprisingly simple and cheap technology has saved the lives of millions of people in the last few years: insecticide-treated bed nets.

The nets protect those who sleep under them and the insecticide, with which they are impregnated, kills the mosquitoes – in this way the bed nets also protect their larger community, very similar to the way vaccinations do not only protect those who receive the vaccine, but also those around them. Such public health measures which protect the individual and the people they are in contact with are particularly successful ways to fight global problems.

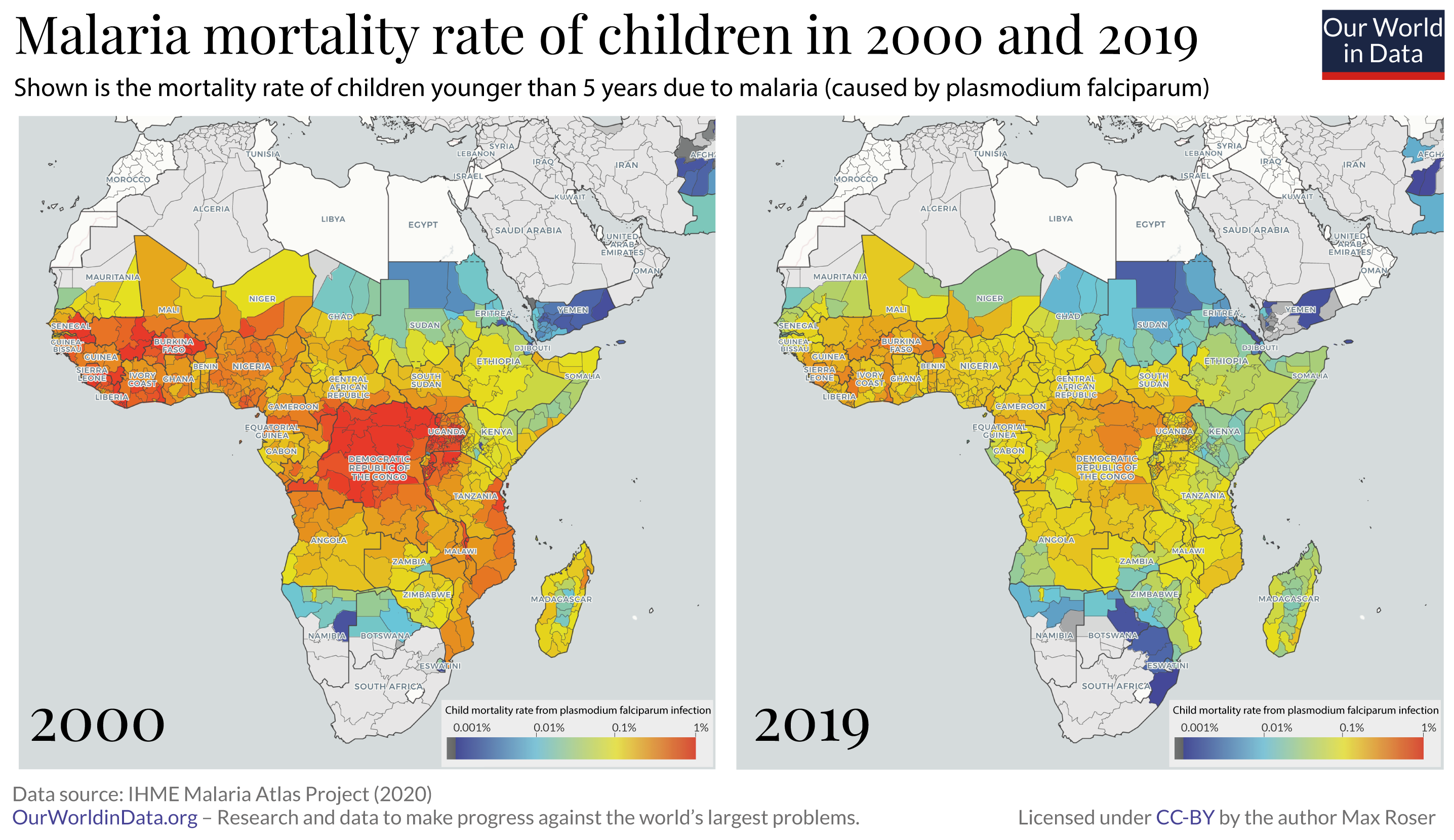

The progress against malaria since the turn of the century is shown in the two visualizations below. The map shows us the change in child mortality due to malaria on the local-level across Africa (for which 2019 is the latest data). The global annual death toll – across all ages – declined from 900,000 to 630,000 per year. It also shows that the disruptions due to the pandemic led to an increase in malaria deaths.

How was this progress possible? The study by Samir Bhatt and colleagues10 in Nature found that three health measures were particularly important for progress against malaria in Africa. By far the most important measure was the just-mentioned distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets; about two-thirds of the averted cases can be attributed to bed nets. The rest was achieved thanks to indoor residual spraying and the treatment of malaria cases with artemisinin, a drug discovered by Tu Youyou. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015 for this achievement.

We can achieve more and you can help

Progress never happens by itself. For millennia our ancestors were exposed to the malaria parasite without defense; the fact that this changed is the achievement of the scientific, political, and economic achievements of the last few generations.

Today we are in the fortunate situation that we have several decades of progress behind us: We can look back and study what worked to use this knowledge to go further.

Some of the most important research in global development asks the question of where additional efforts can do the most good. A charity evaluator that is doing very rigorous work on this is ‘GiveWell’. Their research tells you where your donation can have the largest positive impact. It finds that donations to support the fight against malaria are one of the very most impactful ways for you to donate. At the top of GiveWell’s recommended charities are two organizations that work towards that goal: the Against Malaria Foundation and the Malaria Consortium.

Continuing the successful fight against malaria requires commitment from governments around the world. It is a problem that we might be able to solve with better technology in the future – most likely with a vaccine – if we choose to support scientific research.

But it is also a problem where each of us can individually contribute to progress right now. You can read the research about how your donation can contribute to progress against malaria here: GiveWell.org. If you want to contribute to this progress it is possible to make a donation right there.

We do not have to live in a world in which 1320 children die from a preventable disease every day.

Endnotes

Figures for 2020 according to the WHO: http://www.who.int/malaria/en/

The WHO estimates that in 2020 (latest data, as of writing) 77% of all deaths were in children younger than 5 years old. The IHME’s Global Burden of Disease also estimates that the majority of malaria deaths are in children younger than 5 years. According to their research the share of children younger than 5 among malaria victims fell slightly over the course of the last generation, from 66% in 1990 to 55% in 2019. Here is their data: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/malaria-deaths-by-age

These are the WHO estimates and are calculated based on the two previously cited statistics: 627,000*0.77=482,790.

To not suggest that we have a very precise knowledge of the number of children that die from malaria I have rounded the number from 482,790 to ‘about half a million’.The estimates of the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) – published in their Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study – are different: 643,000 malaria deaths in 2019; 356,000 of them are children younger than five. We have followed up with researchers in this field, but were not able to fully understand why the estimates from the IHME differ in their age-composition from the WHO estimates. To be on the conservative side I am relying on the estimates from the WHO throughout this text, but to provide perspective I also reference the IHME wherever relevant.

For more detail on this data see our entry on malaria.

Alphonse Laveran discovered already in 1880 that the Plasmodium parasite is the cause for malaria. But many attempts to develop vaccines were unsuccessful. Malaria vaccines such as SPf66 were insufficiently effective and until recently none of the scientific efforts led to a licensed vaccine. For an overview see Adrian V. S. Hill (2011) – Vaccines against malaria. In Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011 Oct 12; 366(1579): 2806–2814. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0091.

This has changed somewhat with the malaria vaccine RTS,S, the world's first licensed malaria vaccine, which has been approved by European regulators in 2015. See RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership (2015) – Efficacy and safety of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. In The Lancet, Volume 386, ISSUE 9988, P31-45, July 04, 2015. Its efficacy is however not as high as that of other vaccines.

On the cause of Oliver Cromwell’s death see the FAQs at OliverCromwell.org, on Friedrich Schiller see Bayerischer Rundfunk here, on Abraham Lincoln see ‘The Physical Lincoln’. Several popes also died of the disease as malaria was very prevalent in Italy until recently.

It should however be noted that it is not always possible to diagnose the causes of death of historical figures. The claim that the German renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer died from malaria is for example disputed by Seitz, H. (2010) – "Do der gelb fleck ist … " Dürers Malaria, eine Fehldiagnose. Wien Klin Wochenschr 122, 10–13 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-010-1432-z

See the publication Simon I Hay, Carlos A Guerra, Andrew J Tatem, Abdisalan M Noor, and Robert W Snow (2004) – The global distribution and population at risk of malaria: past, present, and future. In The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2004 June; 4(6): 327–336. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01043-6.

The historical mapping of the prevalence of malaria is based on the pioneering work of Lysenko in the 1960s: Lysenko AJ, Semashko IN. Geography of malaria (1968) – A medico-geographic profile of an ancient disease. In: Lebedew AW, editor. Itogi Nauki: Medicinskaja Geografija. Academy of Sciences, USSR; Moscow: 1968. pp. 25–146. Lysenko AJ, Beljaev AE (1969) – An analysis of the geographical distribution of Plasmodium ovale. Bull. World Health Organization; 40:383–94.

I have recreated that map and written about this research in Roser (2019) – Malaria was common across half the world – since then it has been eliminated in many regions. In Our World in Data.

That malaria was the most common cause of death was even suggested in a Nature article: Whitfield (2002) wrote “Malaria may have killed half of all the people that ever lived”.

Whitfield, J. Portrait of a serial killer. Nature (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/news021001-6

But while there is obviously no hard evidence to establish or refute this claim other epidemiologists were skeptical that this is true. Tim Harford investigated the claim in an episode of the BBC’s “More or Less”: Have Mosquitoes Killed Half the World?

See “Box 4.1 Malaria-related mortality in the 20th century” in the World Health Organization’s World Health Report (1999).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Malaria Atlas Project. Global Malaria Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality Geospatial Estimates 2000-2019. Seattle, United States of America: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020. https://doi.org/10.6069/CG0J-2R97

Shown is the mortality rate due to plasmodium falciparum – direct link to the interactive maps as published by the IHME http://ihmeuw.org/5dhp

For the background see: Weiss, D. J., Lucas, T. C. D., Nguyen, M., Nandi, A. K., Bisanzio, D., Battle, K. E., Cameron, E., Twohig, K. A., Pfeffer, D. A., Rozier, J. A., Gibson, H. S., Rao, P. C., Casey, D., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Collins, E. L., Dalrymple, U., Gray, N., Harris, J. R., Howes, R. E., … Gething, P. W. (2019) – Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000–17: A spatial and temporal modelling study. In The Lancet, 394(10195), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31097-9

Bhatt et al. (2015) – The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207–211 (08 October 2015) doi:10.1038/nature15535

The focus of the study was Africa, where – as the chart shows – most of the recent reduction was achieved.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2022) - "Malaria: One of the leading causes of child deaths, but progress is possible and you can contribute to it". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://staging-owid.netlify.app/malaria-introduction' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-malaria-introduction,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {Malaria: One of the leading causes of child deaths, but progress is possible and you can contribute to it},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://staging-owid.netlify.app/malaria-introduction}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.