How are incomes adjusted for inflation?

Adjusting incomes for inflation is crucial if we want to learn how standards of living are changing. How is this adjustment done?

When looking at data on people’s incomes, it’s usually not the quantity of currency that we’re interested in. It’s what this quantity means for their standard of living – the quantity and quality of the goods and services they can afford.

To study this, we need to compare people’s incomes with the prices of the goods and services they can buy. These change over time – the prices on supermarket shelves that you remember from the past are typically not the same as you’ll see today. Adjusting for this is crucial if we want to use income data to understand how living standards are changing around the world.

For this reason, almost all of the income data you’ll find on Our World in Data is adjusted for inflation.

It’s important to note that here we’re referring to both positive and negative inflation. When incomes are adjusted for inflation, they are also at the same time adjusted for the opposite – deflation.

But how is this adjustment done?

A simple example: adjusting incomes for the price of one good

A simple approach would be to adjust incomes for the change in the price of a single product that is commonly purchased – for example, a loaf of bread. If the price of bread doubles over a period, but your employer still pays you the same income, then you can only buy half as much bread. Your income, adjusted for the inflation of bread prices, has halved.

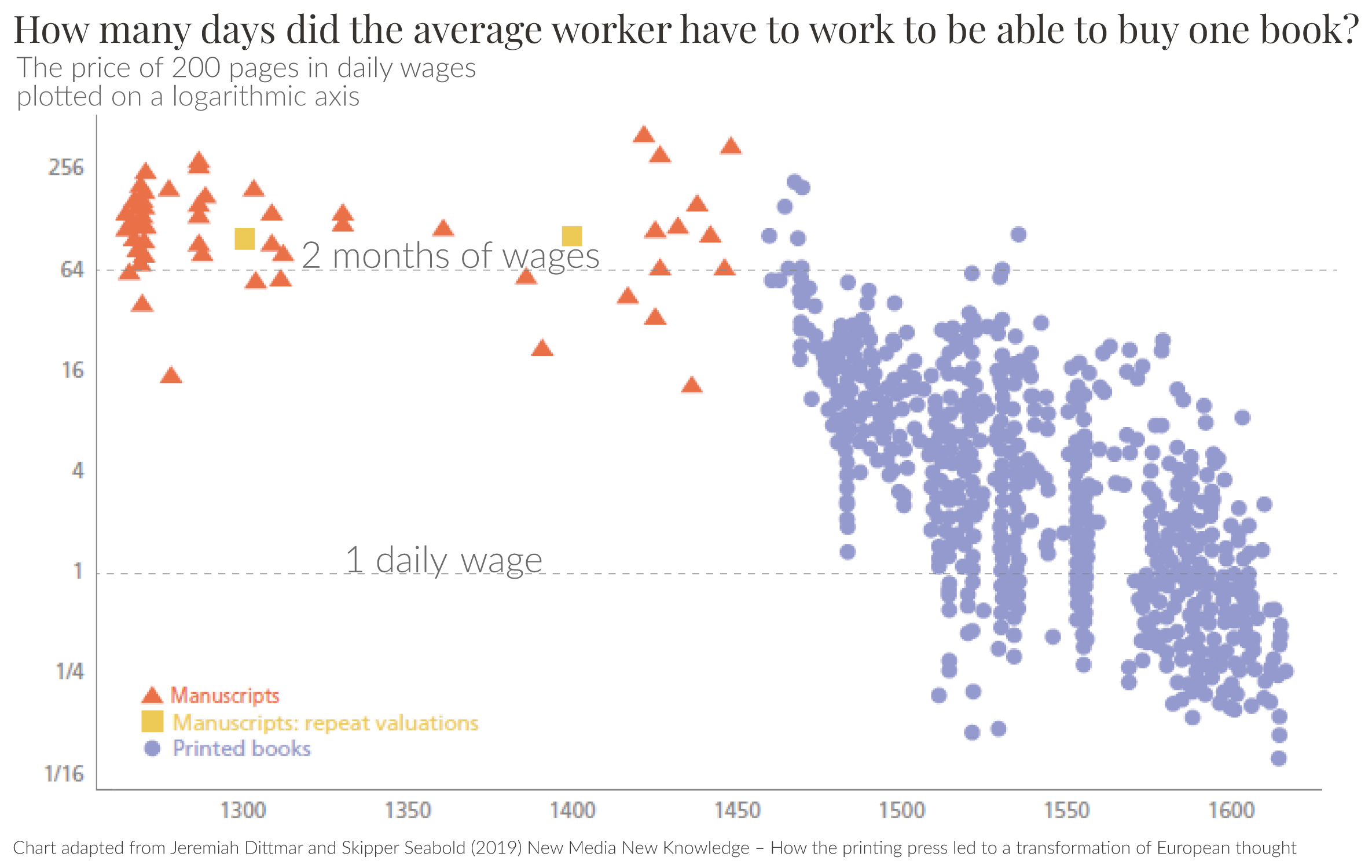

The chart below shows historical data on the relationship between incomes and the price of another commonly purchased product: books. It looks at this relationship the other way around: it shows how long the average worker had to work to afford one book. We see that the price of a book, relative to incomes, rapidly declined with the invention of the printing press in the 15th century.

This means the reverse is also true: incomes, relative to the price of books, rose dramatically. What was once totally out of reach for all but the richest elite – to own a book – became increasingly affordable to the majority. Only by comparing data on incomes to the prices of goods over time can we learn how people’s options and opportunities change.

The Consumer Price Index: a measure of the overall change in prices

Comparing incomes to the price of only one product has an obvious problem: changes in this price may not be representative of all the other products that consumers buy. Changes in the price of a loaf of bread, or a book, may differ from changes in the prices of medicines, heating, or computers. The price of some of these goods may increase while others decrease.

When adjusting incomes for inflation, statisticians rely on a “basket” of goods and services that are representative of the consumption of the average household. Since people buy different things in different countries, these household consumption baskets vary from country to country. The basket is also updated over time, as new technologies emerge making new goods or services available, and as consumption preferences change.1

Statisticians monitor the prices of all the products in this basket and calculate a weighted average: when calculating the overall price level, they give more importance to the products that people spend a large share of their income on. This average price level is then expressed relative to the price level in a chosen base year. This is known as the Consumer Price Index (CPI). In the base year, the CPI is equal to 100, and in other years it shows us the price level relative to that year. A CPI of 120 means that prices are 20% higher than in the base year.

The following chart shows CPI data gathered from national statistical offices by the International Monetary Fund. The base year in this case is 2010, so a CPI of 120 means that prices rose by 20% since 2010.

Nominal incomes ‘deflated’ by a price index give us real incomes

The CPI allows us to compare incomes not to the price of one particular good, but to the broader cost of living. By adjusting incomes with the CPI, we learn not about how many books or loaves of bread people can buy, but about their options and opportunities for consumption more generally.

Income data generally arrives to us in what’s called ‘nominal’ terms: without any adjustment for inflation. If you compare the figure on your paycheck to the figure ten years ago to understand how your income has changed, you are not considering how the price of goods also changed over that time. For this reason, nominal incomes are often referred to as incomes measured in ‘current prices’.

‘Real incomes’ is how researchers and statisticians refer to income data after it has been adjusted for inflation – or ‘deflated’, as it is sometimes called. The changes in real incomes tell us the change in what people can really afford. This is often referred to as income measured in ‘constant prices’: it tells us the amount of goods and services a person’s income could have bought if prices had stayed the same as observed in one particular year (the base year of the CPI).

Such an adjustment is crucial for making meaningful comparisons over time. Only real incomes – measured in terms of constant prices – give us an idea about how the prosperity of a population changes.

An example: Adjusting wages for inflation in the UK

To provide an example of an inflation adjustment, the chart below shows the evolution of average weekly wages in the United Kingdom. It shows three series:

- nominal wages – as measured before any inflation adjustment;

- the consumer price index, used to track the average price level;

- real wages – after accounting for the change in the price level.

Between 1750 and 2015, nominal wages in the UK increased from £0.29 to £492 per week. This is a 1695-fold increase.

But with these higher nominal wages, workers cannot buy 1695 times the value of goods and services, because prices rose considerably over this time too. In this chart, 2015 is the base year used for the consumer price index: in 2015, it has a value of 100. In 1750 it has a value of 0.66. The ratio between these two observations – 100 divided by 0.66 – is 152, and this tells us that the average prices that consumers face increased 152-fold over these 265 years.

To calculate the real wage increase, we need to look at the nominal wage increase compared to the increase in prices. The third line shows real average wages: nominal wages divided by the consumer price index, expressed as a fraction. In 2015, real and nominal wages are the same. In the late 1980s, when prices were around half their 2015 level, real wages are twice the nominal wages.

Over the whole period, nominal wages rose 1695-fold, and prices rose 152-fold. 1695 divided by 152 is 11.2, meaning that average wages in real terms are 11.2 times higher today than back in 1750. If their great-great-grandfathers in 1750 had to work for a year to buy a representative consumption bundle, Brits today have to work for only a bit more than a month to buy a comparable bundle of goods and services.

Other price indexes

The CPI is not the only index that can be used to adjust nominal monetary values. Its focus is on tracking the changes in the prices that consumers face overall. But not all goods produced in an economy are purchased by consumers. Some goods are purchased by firms and used to produce final goods.

The GDP deflator is another commonly-used index that tracks the price of all domestically-produced final goods and services in an economy, as measured by it’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Statisticians calculating a country’s GDP use data that is expressed in current prices – the nominal value of transactions between buyers and sellers of goods and services. The GDP deflator is then used to separate price changes within this nominal data, leaving a measure of the volume of goods and services produced in an economy over time.

There are two main differences between the CPI and the GDP deflator:

- The GDP deflator tracks the prices of goods and services produced in a country. The CPI, on the other hand, measures the prices of goods and services consumed in a country – including those produced elsewhere and imported.

- Secondly, the GDP deflator covers capital goods – goods not bought by consumers.

You can read more about these two price indexes in a detailed guide produced by the OECD: Understanding National Accounts.

Endnotes

For example, in 2012, the UK statistical agency changed the composition of this basket of goods to better reflect the typical consumption basket of households. Tablet computers were added, demonstrating the effect of new technologies, while boiled sweets were removed, reflecting changing preferences. Gooding, Philip. "Consumer Prices Index and Retail Prices Index: the 2011 basket of goods and services." Economic and Labour Market Review 5, no. 4 (2011): 96-107.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Joe Hasell and Max Roser (2023) - "How are incomes adjusted for inflation?". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://staging-owid.netlify.app/how-are-incomes-adjusted-for-inflation' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-how-are-incomes-adjusted-for-inflation,

author = {Joe Hasell and Max Roser},

title = {How are incomes adjusted for inflation?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://staging-owid.netlify.app/how-are-incomes-adjusted-for-inflation}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.