Global economic inequality: what matters most for your living conditions is not who you are, but where you are

How much does it matter to be born into a productive, industrialized economy?

This article was originally published over a year ago. The data shown and discussed in the text are not always the latest available estimates. For more up-to-date data, see our Data Explorers on Poverty and Inequality.

What is most important for how healthy, wealthy, and educated you are is not who you are, but where you are. Your knowledge and how hard you work matter too, but much less than the one factor that is entirely outside anyone’s control: whether you happen to be born into a productive, industrialized economy or not.

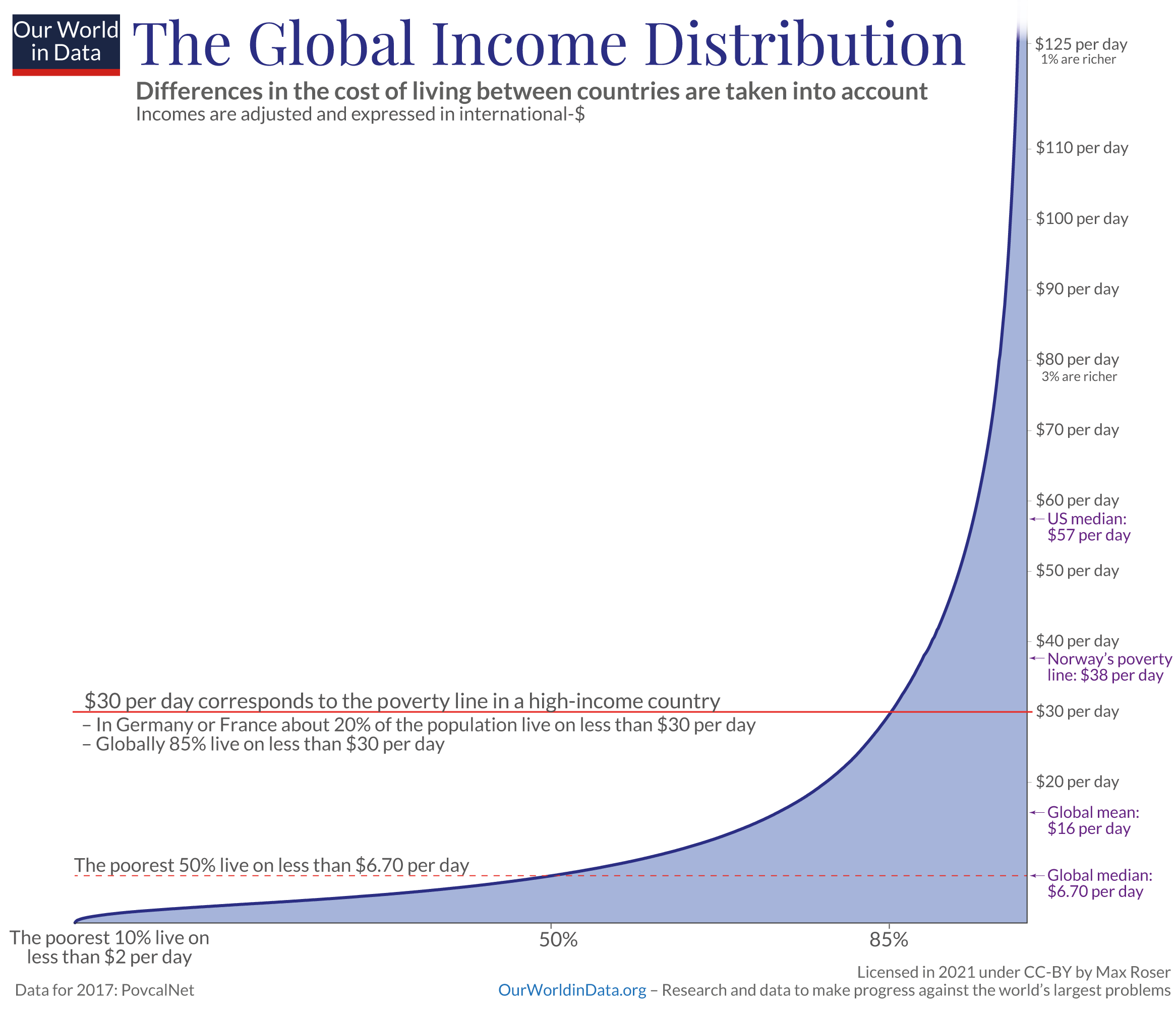

Global income inequality is vast. The chart shows this. As all data throughout this text, it accounts for the differences in the cost of living.

The vast majority of the world is very poor. The poorer half of the world, almost 4 billion people, live on less than $6.70 a day.

If you live on $30 a day, you are part of the richest 15% of the world ($30 a day roughly corresponds to the poverty lines set in high-income countries).

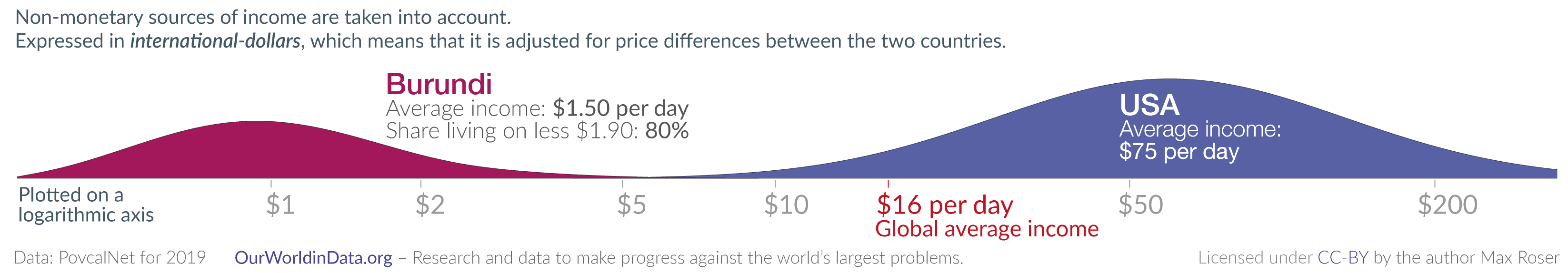

Inequality can be very high within countries. The US – a high-income country with very large inequality – is a prime example. But much of global inequality is inequality between countries. The small chart shows this by comparing the income distribution of the US with the distribution in Burundi.

Vast economic inequality means vast inequalities in living conditions

The large economic inequality is only one dimension of global inequality. There are many other aspects that people care about.

But because a high income is important for good living conditions, these other inequalities map onto the economic inequality. Those who live on higher incomes have advantages in many ways.

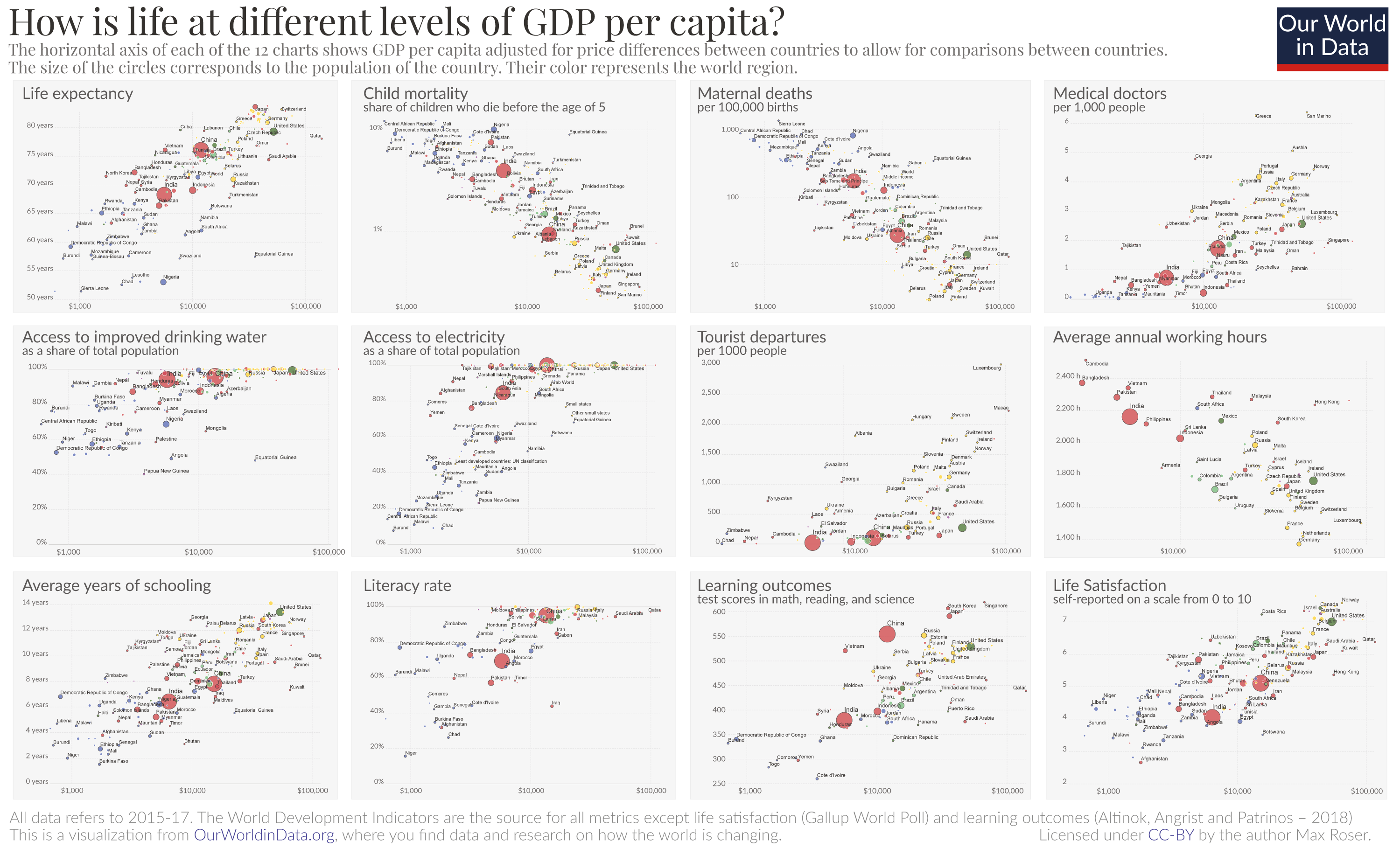

The chart shows what life is like on different income levels in 12 different dimensions.

On the horizontal axis in each panel, you see GDP per capita, measuring the average income in a country. Starting from the top left, these panels show that where incomes are higher, people live longer, children die less often, mothers die less often, doctors can focus on fewer patients, people have better access to clean drinking water and electricity, they can travel more, have more free time, have better access to education and better learning outcomes, and people are more satisfied with their lives.

The inequality in people’s living conditions mirrors the world’s economic inequality.

It is hard to overstate how very large these differences are. Life expectancy in the poorest countries is 30 years shorter than in the richest countries. I have also just written about the large global inequalities in learning outcomes along the economic dimension.

Where a person finds themselves in the unequal global income distribution is mostly determined by where they are

Seeing how much our living conditions depend on the productivity of the economy we live in should matter hugely for our self-understanding and our view of others. In a world of such vast inequalities between countries, it is not who a person is that determines whether they are well-off or poor, but where they are.

To see this, consider a world without any inequality between countries. If all countries were equally rich, where someone lives would not influence where someone ends up in the global income distribution.

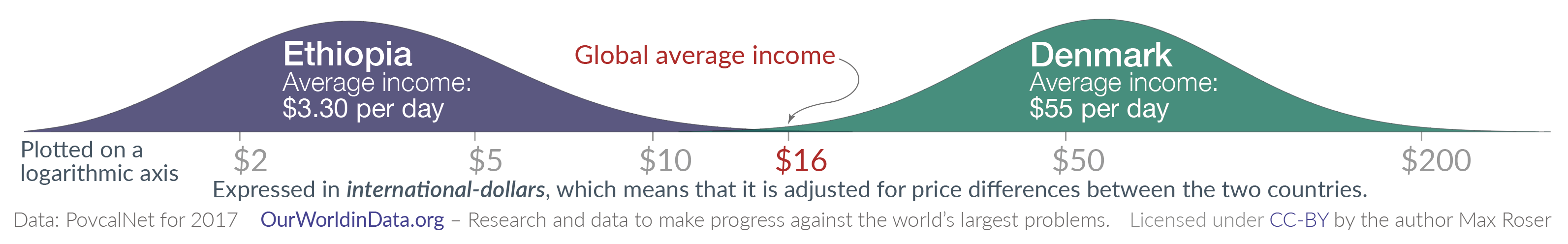

In contrast, consider a situation of extreme inequality between countries, such as today’s inequality between a poor and rich country.1 In this case, the home country of a person determines everything. The shown data for Ethiopia and Denmark makes this clear: the two distributions don't overlap. A person born in Denmark has almost certainly an income above the global average, and someone born in Ethiopia has almost certainly an income lower than that.

Beyond just two countries, how much does a person’s home country matter for where they are in today’s global income distribution?

Inequality researcher Branko Milanovic studied this question and found that the country where a person lives explains two-thirds of the variation of income differences between all people in the world.2 Where a person lives is the most important factor of their income.

For a variety of reasons – from family ties to the political restrictions that impede migration – very few people move between countries. Most of the world population [97%] lives in the country they were born in. And so, for most people, it is not only the country they live in that determines their income but also the country they were born in.

This is not to say that a person’s work ethic, talent, and skills do not matter for their income. They do. But it is to say that all these personal factors together matter much less than the factor that is entirely outside of a person’s control: whether they are born into a large, productive economy or not.

Where you live isn’t just more important than all your personal characteristics, it’s more important than everything else.

The importance of redistribution and economic growth for reducing global inequality and better living conditions

The data I discussed highlights three important facts about our world:

- The extent of global economic inequality is vast;

- Economic prosperity is immensely important for people’s living conditions;

- And where a person finds themselves in the unequal global income distribution is largely outside their control.

What can we take away from these three insights?

Redistribution

Redistribution through the state plays a large role in reducing inequality within countries and could also reduce global inequality. However, the reality is that, no matter in which rich country you pay your taxes, almost none of that goes to the world's poor people.3 The redistribution governments do is not reaching the poorest people: it is domestic, not international redistribution.

If you want to reduce global inequality and support poorer people, you do, however, have this opportunity. You can donate some of your money.

You might be able to live on a little less, and this money could make a big difference to a poorer person.

The most direct way is to send some of your money to poor people; the non-profit organization GiveDirectly makes this possible. Or you can donate to an effective charity that supports the world’s poorest. In the footnote, you can find out how to find such a charity and how I donate.4

Economic growth

Some suggest we can end poverty without additional growth by reducing global inequality. This is not the case. Reducing global inequality can achieve a lot, but it is important to be clear that redistribution alone would still mean that billions of people would live in very poor material conditions. The world is far too poor to end poverty without large growth.

To achieve a more equal world without poverty, the world needs very large economic growth.5

We can see this when we look at our global history. Two centuries ago, the world was much more equal: Average income, measured with GDP per capita in the chart, was low everywhere, and most people were extremely poor.

Since then, some countries have achieved very large growth – Swedes are, for example, about 30 times richer than two centuries ago – while other economies hardly grew at all. This unequal development resulted in the extremely large global inequality of today.

The reality of today's global inequality is cruel. Those who are born into an economy that achieved large growth in the last two centuries grow up in much better living conditions than those who happen to be born into a poor economy. Economic growth for billions of people in poverty is what we need to end this injustice.

Those places that have achieved large growth show how much better the living conditions can be for all.

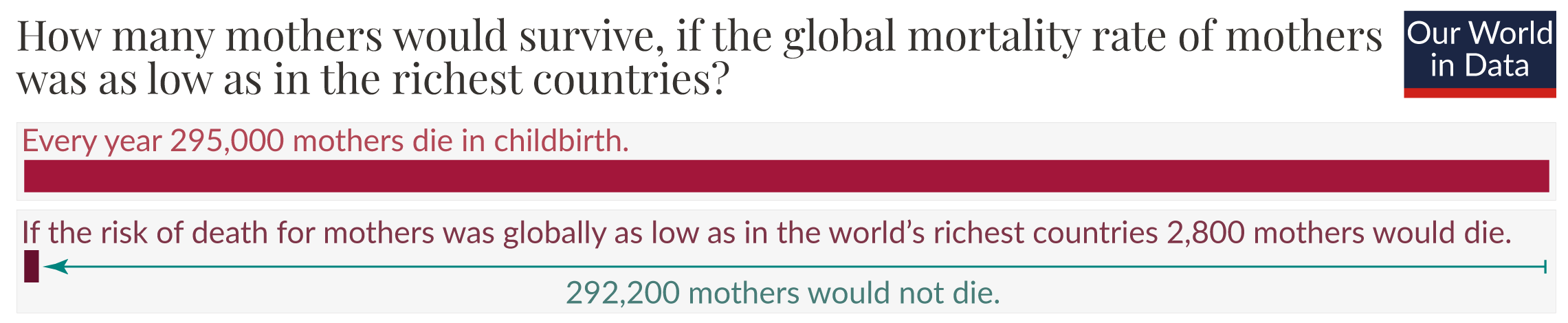

To take one concrete example, let’s consider maternal mortality. In high-income countries, where mothers can rely on well-equipped hospitals and support from doctors and midwives when complications occur, maternal deaths have become rare (the risk of death has declined 300-fold in the last generations). But in the rest of the world, it is still very common: every year, 295,000 mothers die just when they give life to their child.

What would the world look like if the risk of death for mothers was globally as low as in the world’s richest countries? The vast majority of mothers who die this year would survive.6

We know that this is possible. This is what the historical perspective makes clear; all places with good living conditions today were extremely poor until just a few generations ago.

Conclusion

What we have seen in the data here is one of the most important insights of development economics: people live in poverty not because of who they are, but because of where they are. A person’s knowledge, skills, and how hard they work all matter for whether they are poor or not – but all these personal factors together matter less than the one factor that is entirely outside of a person’s control: whether they happen to be born into a large, productive economy or not.

What gives people the chance for a good life is when the entire society and economy around them changes for the better. This is what development and economic growth are about: transforming a place so that what was previously only attainable for a few comes into reach for all.

Continue reading on Our World in Data:

How much economic growth is necessary to reduce global poverty substantially?

Acknowledgments — I want to thank Joe Hasell and Toby Ord for their feedback on this article and visualizations.

Endnotes

I have written a detailed description of this chart and the shown data in my post on Global poverty in an unequal world.

Branko Milanovic (2015) – “Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined By Where We Live?”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(2): 452-460. Online here: https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/REST_a_00432#.VKCF2CcA

He wrote a summary on VoxEU https://voxeu.org/article/income-inequality-and-citizenship

See this map of Net ODA as a share of the donor country’s GNI. Few countries reach the goal of 0.7% of national income, meaning the share of taxes paid on ODA is extremely small. I think it should be higher, development aid is one way in which the populations of the richest countries can improve the situation in the world’s poorest places.

One of the most important things to know about charities is that their impact varies hugely – some are ineffective or even do more harm than good. In contrast, others can do extremely good work on a large problem in a very cost-effective way.

GiveWell is a research team that finds the charities that make the biggest difference per each dollar or euro you donate. On their site, you will find their recommended charities and very transparent and in-depth research on how they arrived at these recommendations.

Giving via GiveWell is one way to donate that I'd recommend.

The way that I donate is via Effective Altruism Funds. They also rely on Givewell's research, but they also focus on other areas. As a donor, you can set your priorities between these different areas, but beyond that, you trust the team of the Effective Altruism Funds to make decisions for you. This has the advantage that their team has more knowledge about the various effective charities than you, or I can possibly know, which gives them the chance to give to those charities that have the greatest potential and need at a particular time. I pay into the 'Fund' with a recurring transfer every month.

For evidence on this, see my post ‘How much economic growth is necessary to reduce global poverty substantially?’

In the world’s richest countries, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is more than 100-fold lower than the global average (211/2=105.5-fold).

In the world’s richest countries, the MMR per 100,000 live births is 2; worldwide, it is 211. [Source]

- Worldwide, 295,000 mothers die every year. [Source].

- This means (100,000/211)*295,000 =139,810,426 births yearly.

- If the global MMR were 2 rather than 211 per 100,000, then this would result in (139,810,426/100,000)*2=2,796 Deaths of mothers.

- [Or a more straightforward calculation of the same: 295,000/(211/2)=2,796]

Every year 295,000 mothers die in childbirth. If the risk of death for mothers were globally as low as in the world’s richest countries, 2,800 mothers would die. 292,200 mothers would not die.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2021) - "Global economic inequality: what matters most for your living conditions is not who you are, but where you are". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://staging-owid.netlify.app/global-economic-inequality-introduction' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-global-economic-inequality-introduction,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {Global economic inequality: what matters most for your living conditions is not who you are, but where you are},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2021},

note = {https://staging-owid.netlify.app/global-economic-inequality-introduction}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.