The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reports that tens of thousands of species are threatened with extinction.

But what does it mean for a species to be ‘threatened with extinction’? How do researchers evaluate extinction risk?

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is regarded as the definitive source of extinction risk. Every year, the IUCN publishes its latest assessment of the status of each evaluated species.

In this article, we look at how species are categorized and assessed for their extinction risk.

The 9 categories of extinction risk

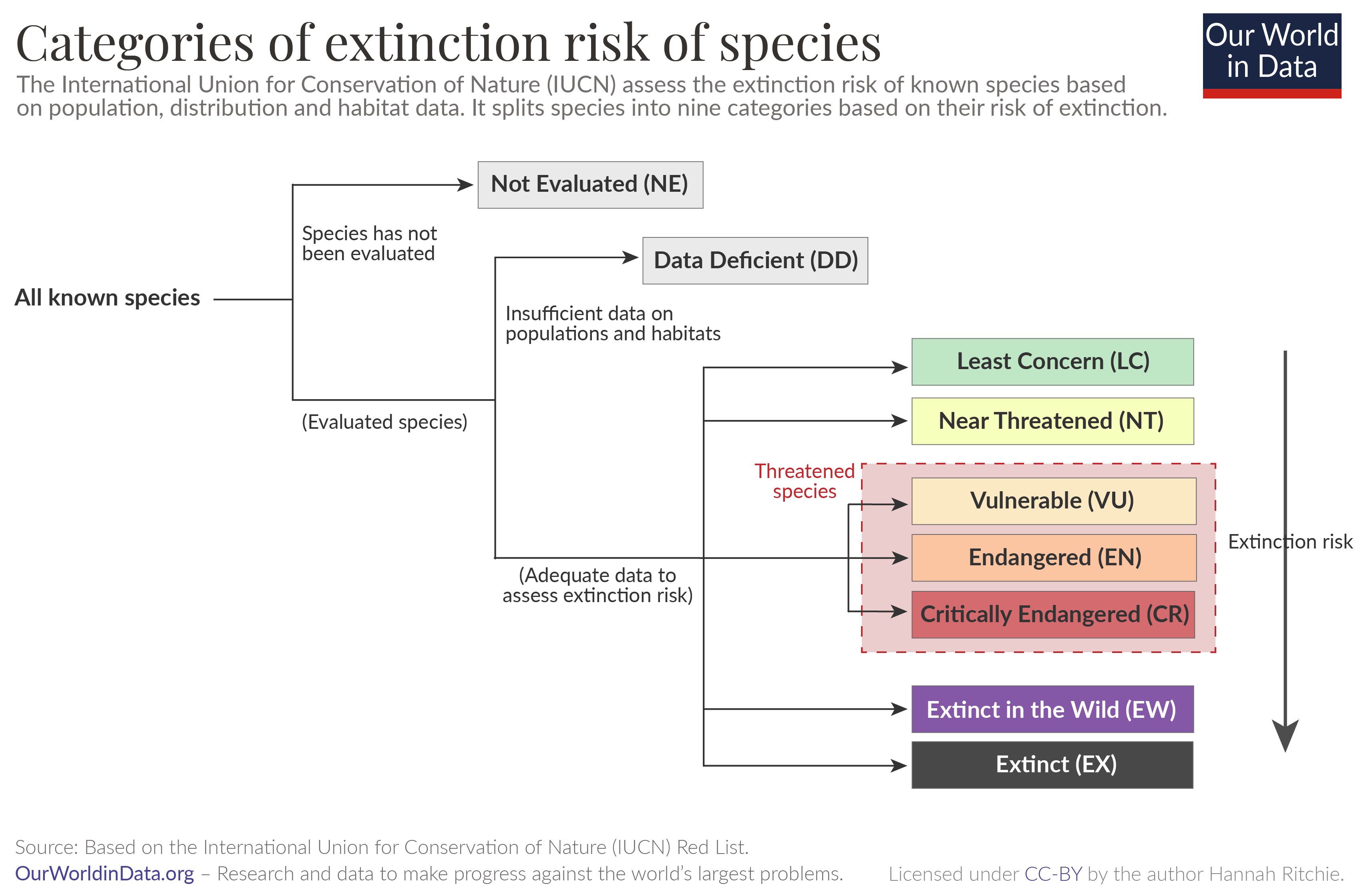

Each species is assessed against a standardized list of criteria.1 Based on these answers, a species is assigned to one of nine categories:

- Not Evaluated (NE)

- Data Deficient (DD)

- Least Concern (LC)

- Near Threatened (NT)

- Vulnerable (VU)

- Endangered (EN)

- Critically Endangered (CR)

- Extinct in the Wild (EW)

- Extinct (EX)

How these categories relate to each other is shown in the visualization.

The first two categories are about species that we can’t say much about.

Not Evaluated (NE). The first question researchers ask is whether we know enough about a species to evaluate their status. If a species doesn’t meet this criterion, they are not evaluated and removed from the assessment process. As part of the IUCN’s aims, each species is re-evaluated every five to ten years; if our understanding has developed by this point, then a species can be evaluated later.

Data Deficient (DD). For some species, we do not have sufficient data to assess their risk of extinction. We might know a lot about their biology, but without adequate data on their populations and occurrence, a species’ extinction risk can’t be evaluated.

That leaves us with seven categories where we have enough data to make an assessment.

Researchers draw on a large number of extensive studies of a species’ population size, range, and habitat, and how these are changing over time. Later we’ll look at the specific criteria that they’re evaluated against.

These are the seven categories, from extinct through to species that are abundant and of little concern:

An Extinct (EX) species is one for which there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. Researchers declare this when no individuals are found in exhaustive studies of its known or expected habitats for a long period of time. This includes the golden toad and the Japanese sea lion.

An Extinct in the Wild (EW) species fits the criteria for ‘Extinct’ – exhaustive surveys have found no individuals in its expected habitats – but individuals still exist in captivity or as naturalized populations outside of its normal, historical range.

That then leaves us with five categories by which species are assessed for their risk of extinction.

A Critically Endangered (CR) species faces an extremely high risk of extinction. As explained in the next section, this is based on the criteria of having a very small population size, a very rapid decline in population, or a large restriction in the range of a species. One of the metrics that categorizes a critically endangered species is if quantitative analysis shows that there is a greater than 50% chance that it goes extinct in the wild within 10 years. This does not necessarily apply to species classified as critically endangered under other criteria.

An Endangered (EN) species faces a very high risk of extinction. As explained in the next section, this is based on the criteria of having a very small population size, a very rapid decline in population, or a large restriction in the range of a species. One of the metrics that categorizes an endangered species is if quantitative analysis shows that there is a greater than 20% chance that it goes extinct in the wild within 20 years. Again, this does not necessarily apply to species classified as endangered under other criteria.

A Vulnerable (VU) species faces a high risk of extinction. One of the metrics that categorizes a vulnerable species is if quantitative analysis shows that there is a greater than 10% chance that it goes extinct in the wild within 100 years.

A Near Threatened (NT) species does not qualify as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable now, but according to the researchers’ assessment, it is close to meeting this definition soon, based on recent trends.

A Least-Concern (LC) species is widespread, abundant, and not threatened with extinction.

The IUCN will often discuss species as being threatened with extinction. That’s the most commonly reported metric. On Our World in Data, we show both the number or share of studied species that are ‘threatened with extinction’ according to the IUCN.

Threatened species are those classified as either critically endangered, endangered, or vulnerable. It is the sum of species in each of these three categories.

How do researchers assess the risk of extinction?

We’ve covered all the categories that species are classified into. But how do researchers arrive at the categorization? How do researchers decide how vulnerable a species is to extinction?

Species are evaluated across four key metrics. It’s important to note that this doesn’t include every possible way to assess the future health of a species: aspects such as food supplies or future hunting threats aren’t defined as measure risks.

Any of these would indicate that a species is at risk:

- If the population size is very small.

- If the population size is small and it’s declining.

- If there has been a large decline in population size (regardless of its total size).

- The geographic range of the species – the area or region it lives in – is small and declining.

Within each of these measurements, researchers set thresholds that detail whether a species is vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered.

Take metric (1): the size of the population. A species is considered ‘Critically Endangered’ if there are fewer than 50 mature individuals globally. It’s ‘Endangered’ if there are fewer than 250 individuals, and ‘Vulnerable’ if there are fewer than 1,000.

Or metric (4): the geographic range of the species. A species is considered ‘Critically Endangered’ if its area of occupancy is less than 10 square kilometers (km2). It’s ‘Endangered’ if this area is less than 500 km2, and ‘Vulnerable’ if it’s less than 2,000 km2.2

The final metric that researchers use to classify species is the probabilistic assessment on the likelihood of extinction within a given time period. For example, a critically endangered species is expected to have a greater than 50% chance of extinction within 10 years if threats are not reduced, and protections put in place.

You can find a complete list of the criteria for each extinction risk category in the IUCN’s definition guide.These assessments are conducted and prepared by the IUCN’s network of specialist groups: this includes 10,500 volunteer experts across more than 160 Specialist Groups, Conservation Committees, and Task Forces. There is, for example, an IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group that focuses on the monitoring of African elephant populations. These volunteers and expert groups do not necessarily do all of the original research themselves: they will often form their assessments based on peer-reviewed academic literature conducted by other researchers.

Assessments of wildlife populations can be uncertain

The number of described species in the world is now over 2 million (with more than 1 million being insects, which the IUCN does not assess).3 The IUCN has assessed more than 150,000 species for their extinction risk. A large number, but a small fraction of the total.

They aim to re-evaluate every species in a peer-reviewed process every five years – every ten years at most. Many at-risk species are monitored and evaluated more frequently. That’s an incredible achievement. But it’s still just a fraction of the species that exist. We don’t know the extinction risk for most of the world’s species.

Additionally, the uncertainty can be high for the species that the IUCN researchers have evaluated. The dynamics of wildlife populations can change quickly; can vary a lot from one location to another; and measurements are prone to error.

In this case, a species might be classified as ‘data deficient’. But often the data is deemed adequate, just with a higher level of uncertainty.

A species moving from one category to another does not always mean a dramatic improvement or regression in its health. It can simply be a re-evaluation with better data.

Despite these challenges, the IUCN Red List provides an essential resource to understand the extinction risk of our world’s species. It highlights which species are most at-risk, so we can protect them.