There are few events more tragic than the loss of a child. It’s therefore hard to grasp just how common child deaths were for almost all of our history.

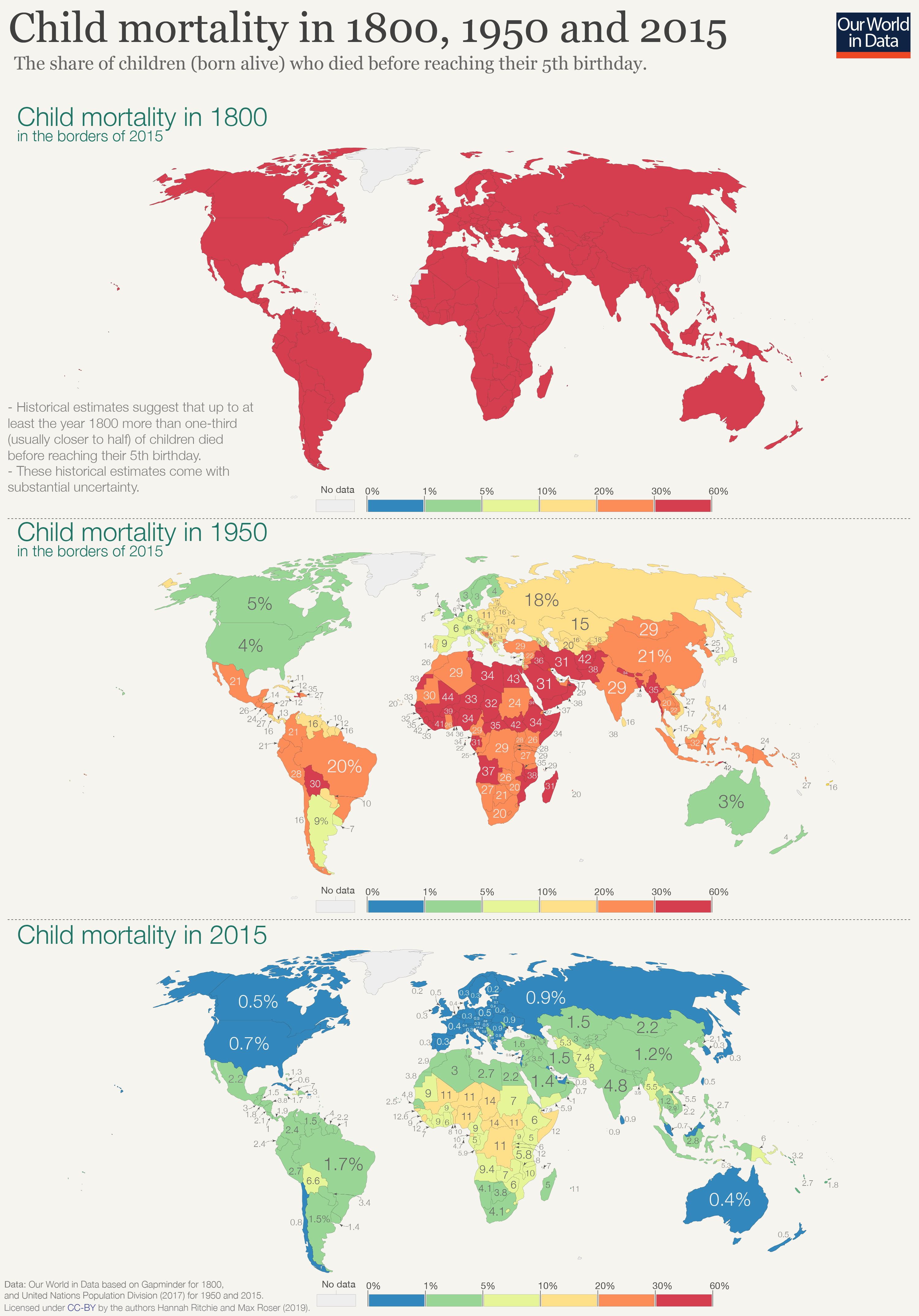

In the map here we’ve visualized the estimated child mortality rate – the share of children (born alive) who died before reaching their 5th birthday – in 1800, 1950 and 2015.

1800: Demographic research suggests that through to at least the year 1800 more than one-third of children failed to reach the age of five. Despite estimates in 1800 coming with substantial uncertainty, it’s expected that in some countries rates could have been as high as every 2nd child. Let’s think about what this meant for parents of this period. The average woman in 1800 had between 5 to 7 children.1

Parents probably lost 2 or 3 of their children in the first few years of life. Such loss was not a rare occurrence but the norm for most people across the world.

1950: By 1950, the outlook has changed dramatically — but only for some. For the richest countries at the time — across Europe, Australasia, North America, and some parts of South America — child mortality had fallen to less than 5 percent (1-in-20). The fertility rate across these countries had also fallen to around 2 to 3 children per woman. Major improvements in living standards, medical knowledge and care, nutrition, water and sanitation, and treatment of disease had transformed outcomes for mothers and children. For the first time in millennia, most parents would not lose a child. Child mortality was still fairly common, but no longer the norm.

But 1950 was also a divided world. Child mortality rates across the rest of the world were still unimaginably high. With one-in-three children (sometimes higher) dying in their first few years, most parents across Africa, Asia and much of South America were probably still losing several children.

2015: If we fast-forward to 2015 we see how far the world has progressed. Child mortality continued to fall across Europe, North America and Australasia; in 2015 around 1-in-200 children died before their 5th birthday. But the rest of the world has also seen dramatic improvements. Many countries across South America, Asia and Africa have reduced child mortality to 1 to 2 percent (between 1-in-50 and 1-in-100). China reduced child deaths from 1-in-3 to 1-in-100; India from 1-in-4 to 1-in-20; Kenya from 1-in-3 to 1-in-20; and Tanzania from greater than 1-in-3 (40 percent) to 1-in-20. The countries where child mortality is highest today have comparable rates to many countries across Europe in 1950.

Many of us are not aware that child mortality has declined substantially everywhere and still imagine the divided world as it was in 1950. A divided world where progress in the richest countries was dynamic, but static and persistently bad elsewhere.

As the chart shows, substantial declines in child mortality have occurred across all regions. Average rates in Africa are now lower than the European average in 1950.

- global rates fell five-fold from 22.5 percent to 4.5 percent;

- European rates from 11 to 0.6 percent;

- North American rates from 3.8 to 0.6 percent;

- Oceania rates from 9 to 2.5 percent;

- Latin American rates almost ten-fold from 20 to 2.4 percent;

- Asian rates from 1-in-4 children (25 percent) to below 1-in-20 (3.5 percent);

- African rates from 1-in-3 children (32 percent) to below 1-in-12 (8 percent).

The frequency of child deaths today (as high as 1-in-7 in the handful of poorest cases) is still tragically high. We must do better. But we also know that we can do better. History has shown that no country is an exception to this.