The International Labour Organisation states in its latest World Report on Child Labour (2013) that there are around 265 million working children in the world—almost 17 per cent of the worldwide child population. According to the publicly available data discussed in more detail below, Sub-Saharan Africa is the region where child labour is most prevalent.

While absolute numbers are still high, particularly in those countries with the lowest standards of living, from a historical viewpoint there are concrete examples of countries that managed to virtually eliminate widespread child labour in the course of a century. The United Kingdom is a case in point. In terms of recent developments, global trends show a significant reduction in child labour over the last couple of decades. However, there is wide dispersion in the progress that different countries have achieved.

Interactive charts on Child Labor

Historical studies suggest that child work was widespread in Europe and North America in the 19th century, but declined very rapidly at the turn of the 20th century. The available historical evidence seems consistent with the fact that industrialisation in Western countries initially increased the demand for child labour, but then eventually contributed towards its elimination.1

These visualizations show the share of children in employment for the UK and the United States at the turn of the 20th century. For the US chart you can add data on rural versus urban child labour trends: for both boys and girls, the incidence of child labour was higher in rural populations.

Whilst consistent survey data on child labour in the UK is limited beyond 1911, some estimates of 20th century labour have emerged. These statistics show the significant impact of the First and Second World Wars on childhood employment. Following a reported spike in employment during the First World War (1914-1918), rates of childhood labour appeared to fall to approximately 6-7 per cent of children aged 12-14 in England and Wales.2

This would make the UK’s rate of reduction in child labour slightly faster than that of the United States. However, with the onset of the Second World War in 1939, the incidence of child employment appeared to show another spike- by 1944, this had increased again to 15.3 per cent of 12-14 year olds.3

How do the child labour figures above compare to current global estimates? This visualization plots the series for the UK, US, and also Italy, together with two recent global series. The different series in this chart are not perfectly comparable because of differences in the definitions. However, they do provide a rough sense of perspective.

As we can see, the incidence of child labour in England in 1900 was similar to global incidence a century later. Global rates of child labour today are similar to those of Italy in the 1950’s at around 10 per cent. In the next section we explore these series in more detail and discuss recent developments.

A complete and overview of recent global trends in child labour can be found in the ILO’s report Marking Progress Against Child Labour (2013)4 produced by the organization’s International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). This report presents global estimates and trends for the period 2000-2012.

The two charts here show the ILO report data. This first chart presents the recent changes in the world-wide share of children (ages 5-17) in employment.

As we discuss below, there is lack of consensus regarding the appropriate ages for measuring child labor, particularly for the purpose of cross-country comparisons and global aggregates. The age bracket ranging from 5 to 17 years of age is common in many UN reports, but there is evidently a need to differentiate work at different ages, since children in their teenage years are less vulnerable to workplace abuse. Other common age brackets are 5-11 and 5-14 years of age.

The second chart presents global trends using estimates in two age brackets: 5-14 and 15-17 years of age. Unfortunately these global estimates are not broken down by gender, and are not available for other age brackets. However, the pattern is consistent with the remark made above: child labour has been going down in recent years.

The ILO Programme on Estimates and Projections of the Economically Active Population (EPEAP) has been producing statistics on labour force participation (for adults and children) since 1950, through the ILO’s cross-country database known as LABORSTA. Basu (1999)5 uses this source to produce global labour force participation rates for children (ages 10-14) in the period 1950-1995.

This visualization presents the corresponding trend using the data published in Basu (1999). While these estimates are informative about child labour, they cannot be linked directly to those of children in employment published by the ILO IPEC for the period 2000-2012 due to issues of comparability; specifically, the IPEC and EPEAP estimates discussed above rely on different survey instruments covering a different set of countries, and break up the relevant population in different age brackets.

Many studies rely on the LABORSTA data to shed light on the extent of child labour in the 20th century. However, this source is generally believed to understate the extent of child labour, since data is not collected for work inside the household (not even market work). Nonetheless, regardless of discrepancies between these two sources, the trends tell a consistent story: the share of economically active children in the world has been going down for decades.

Contrary to popular perception, most working children in the world are unpaid family workers, rather than paid workers in manufacturing establishments or other forms of wage employment. This visualization6 shows a breakdown of 2012 global estimates of child labour by employment status.

Schultz and Strauss (2008)7 compile information from a number of different sources (mostly country-specific datasets from national statistics offices—see the original paper for detailed sources) to provide a picture of the industrial composition of economically active children. This table8 presents their results. In almost every listed country, a majority of economically active children work in agriculture, forestry, or fishing.

A point that is also worth emphasizing here is the lack of consistency in the age brackets for which child labour estimates are available.

Child labour across countries today

This visualization shows the share of children (7-14 years) in employment for a number of countries (for the years in which data is publicly available from the World Bank consolidated dataset).

As it can be appreciated, the prevalence of child labour varies widely by country; for instance, the share of children in employment (here defined in terms of being economically active for one hour a week) was fifteen times larger in Uganda than in Turkey according to 2006 estimates. While most countries exhibit a downward trend, many countries are lagging.

Switch to the map view in this chart to compare the level of child labour between countries. Sub-Saharan Africa is the region where child labour is most prevalent, and also the region where progress has been slowest and least consistent.

As we discuss in more detail below, child labour is by definition problematic whenever it interferes with the children’s development. Because of this it is informative to study child labour specifically when it is coupled with absence from school.

The visualization here shows the share of children in employment who work only (i.e. those children who are economically active and do not attend school). Again, there is wide variation across countries; while in Latin America the majority of children who are economically active also attend school, in sub-Saharan Africa this is not the case. However, trends are encouraging on the whole, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where the problem is most acute. The next section exploring correlates, determinants and consequences of child labour, provides more information about the link between work and school attendance.

The harmful consequences of child labor are partly determined by the intensity of work, and how it affects time allocation in other activities, such as playing or learning (more on this below). Hence, to understand child labor it is crucial to understand time allocation.

The chartshows, country by country, the weekly average of hours worked by children (ages 7-14) who are economically active.

As we can see, average hours worked by children vary widely across countries, even at similar levels of GDP per capita. For example, while average incomes in Bangladesh and Nepal are roughly similar, in the former economically active children spend more than three times as much time working.

In fact, even across countries with similar labor force participation of children, differences in average hours worked are large.

Current gender gaps

In the majority of countries boys are more likely than girls to be engaged in economic activity. The visualization here presents the incidence of child employment for boys vs. girls by country, according to the most recent estimates available from the data published by the World Bank. Here, the diagonal line marks equal values for boys and girls; as it can be appreciated, most countries lie below the diagonal line.

As it has already been mentioned, child labour is particularly problematic to the extent that it hinders the children’s development, notably by interfering with schooling. Since time is a scarce resource, the extent to which children’s employment is linked to school attendance depends on the type and number of hours worked.

In countries where children tend to work longer hours, it is more common that working children remain out of school. The chart here shows this by plotting country-level average hours worked by children against share of working children who are out of school.

The chart here shows aggregates, but we can see a similar relationship between school attendance and hours worked using micro data (i.e., plotting the relationship by pooling observations across individual households).

The visualization from Schultz and Strauss (2008) presents evidence of this link using micro data from UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (2000 and 2001).9 It plots school attendance rates for children 10–14 against total hours worked in the last week (by type of work) with 95 percent confidence intervals (labeled CI and plotted in lighter shades).

The steepest part of the curves are in the range 20-45 hours, suggesting—as one would naturally expect—that it is most difficult for a child to attend school when approaching full-time work. This evidence also shows that there are no significant difference by domestic or marketed work.

The above relationship between work and schooling is informative about the impact of children’s work on schooling, but is not sufficient to establish causality; there are many potential economic and cultural factors that simultaneously influence both schooling and work decisions; and in any case, the direction of the relationships is not obvious—do children work because they are not attending school, or do they fail to attend school because they are working?

A number of academic studies have tried to establish causality by attempting to find a factor (an ‘instrumental variable’) that only affects whether a child works without affecting how the family values other uses of the child’s time (e.g. Rosati, F., Rossi, M. (2003);10 11). While these studies can be criticized on the grounds of the validity of the instrumental variables used, they seem to agree on the fact that there is a stronger association between child labour and schooling than the raw data would suggest.

Cross-country data on child labour and economic growth suggests a strong negative correlation between economic status and child labour. This visualization depicts the cross-country incidence of child labour (share of children ages 7-14 involved in economic activity) against GDP per capita (PPP adjusted GDP per capita in international dollars). To provide some context regarding the absolute number of children, each country’s observation is pictured as a circle where the size of the circle represents population aged 5-14.

This evidence cannot be interpreted causally; as before, countries differ in many aspects that may be associated with child labour choices and income. But there are a number of reasons why, conceptually, child labour might be indeed caused by poor living conditions. For example, children might only work if the parents are unable to meet subsistence conditions; or it could be the case that parents allocate more of the children’s time to schooling as they afford the necessary inputs for schooling (text-books, uniforms, etc).

Partly following this logic, several countries have implemented cash transfer programmes in an attempt to discourage child labour and increase schooling. The idea behind these programmes is that the cash transfers are conditioned on a number of desirable actions, including sending children to school; and in doing so, they lower the relative costs of schooling and raise family income.

Schultz (2004)12 evaluates one such program in Mexico (the so-called ‘Progresa’ program) and finds a significant reduction in wage and market work associated with eligibility for Progresa. Similar findings have been found in other countries as well. The literature often refers to these programmes as the prime example of “collaborative measures” against child labour: non-coercive interventions that alter the economic environment of decision makers in order to make them more willing to let children stay out of work.

Definitions and measurement

Broadly speaking, the term “child labour” is defined as the employment of children in any work that deprives them of their childhood and dignity, and that is harmful to their physical and mental development.

The ILO defines child labour as work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and that interferes with the children’s schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school, either by obliging them to leave school prematurely, or by requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work (a general definition along these lines can be found in the ILO’s Child Labour website). The ILO’s Convention No. 138, adopted in 1973 and ratified by most countries of the world, stipulates the relevant ages that different countries use to define child labour.

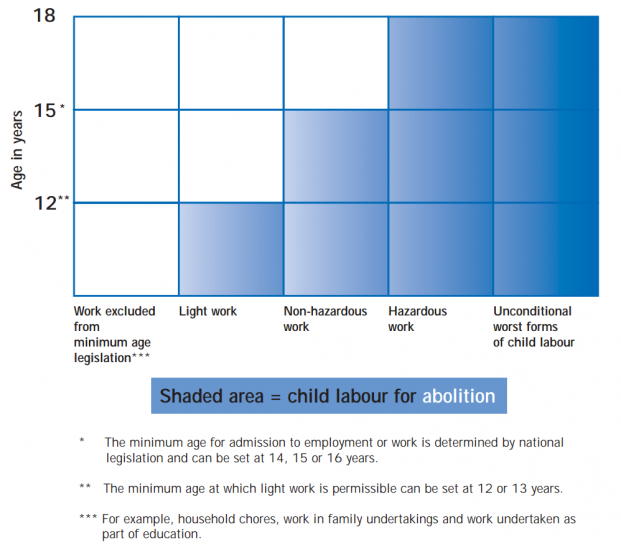

According to the definition provided above, whether or not a given job is considered ‘child labour’ depends on the details of the actual context — the child’s age, the number of hours worked and the type of tasks performed. The chart here, from Hilowitz (2004)13, shows a diagrammatic classification of child labour (shaded region) depending on age and type of work.

This chart shows why it is difficult to produce estimates of child labour that are suitable for cross-country comparisons: there are differences in legislation, and age matters relative to the type of work.

According to the conceptual classification used by the ILO, children in child labour include those in worst forms of child labour and children in employment below the minimum age, excluding children in permissible light work — where “permissible light work” is defined as any non-hazardous work by children (ages 12 to 14) of less than 14 hours during the reference week (for more details see ILO-IPEC, Diallo, Y., et al. (2013)).15

Global aggregates and cross-country data are not publicly available for ‘children in child labour’ as per the conceptual definition above. The ILO tends to report figures of economically active children for the broadest age bracket (5-17 years of age). The World Bank – World Development Indicators also report figures of economically active children, but use a narrower age definition (7-14 years of age). In both cases, ‘economically active’ refers to children who work for at least one hour during a reference week.

Because of the limitations of the data, academic studies often focus on children’s time allocation, which leaves more room for exploring the consequences of employment on other activities, such as school attendance. These studies tend to rely on country-specific survey data.

Basic classification of child labour standards by age – Hilowitz (2004)14

Many studies distinguish between ‘children in child labour’ and ‘children in employment’, while using the terms ‘working children’, ‘children in economic activity’ and ‘children in employment’ interchangeably. In such cases, the former (‘children in child labour’) are considered a subset of the latter (‘children in employment’ or any of the aforementioned interchangeable terms).

As noted above, children in child labour include those in worst forms of child labour and children in employment below the minimum age, excluding children in permissible light work—where “permissible light work” is defined as any non-hazardous work by children (ages 12 to 14) of less than 14 hours during the reference week (for more details see ILO-IPEC, Diallo, Y., et al. (2013)).16

Data quality

Schultz and Strauss (2008) provide a complete account of the particular challenges that arise from measuring children employment through household surveys. The authors highlight difficulties arising from coverage (i.e. capturing the most vulnerable children through random sampling) and accuracy (i.e. misreported hours worked and sensitivity to the recall period used).

Cunningham and Viazzo (1996) and Humphries (2010)17 note similar challenges in the use of national census and household survey data for accurate coverage of the incidence of child labour. There remains a generally accepted consensus that census data is likely to underestimate the scale of child labour for several reasons. This is particuarly important in case of later censuses, where national regulation required children to be in education; in this case, child labour was likely to be underreported, for fear of prosecution. These estimates therefore often underrepresent the numerous children, particularly girls, who worked unpaid at home. Since census results typically capture data from households, this often limits coverage to children who live within a family household. This can exclude children either orphaned, or living on the streets- in many cases, we might expect the incidence of child labour to be more prevalent in these demographics.

Specifically regarding the information published by the World Bank in their World Development Indicators, it is important to highlight that, while definitions are standardized (children in employment are always defined as those children aged 7-14 involved in economic activity for at least one hour in the reference week of the corresponding survey), the data-collection instruments are not standardized across the different sub-sources feeding the consolidated dataset. It is because of this that many policy reports (such as the much-referenced report Marking Progress Against Child Labour (2013) ) ‘homogenize’ the data before reporting estimates, by correcting for discrepancies in the underlying survey instruments. Those visualizations presented here that use the consolidated data published by the World Bank have not been corrected.

Issues of consistency across different survey instruments in the World Bank consolidated data can help us explain country-specific patterns that are otherwise difficult to interpret. Consider the case of India. As can be appreciated in this visualization, the incidence of child labour in India seems to jump up in 2006, only to go back in 2010 to the levels that would have been predicted with the observations from 2000 and 2005. After checking the survey catalogue, it becomes clear that the estimates for 2006 come from the country’s Demographic and Health Survey, while those for the other years come from consecutive rounds of the National Sample Survey. Cases such as this illustrate why current academic studies typically rely on data stemming from a single survey instrument, such as UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

Data and research gaps

In addition to the above-mentioned difficulties related to measurement, there are also important limitations in the way child labour data is made available.

As pointed out before, most UN reports publish global child labour estimates for custom age brackets, and only sometimes break down estimates by gender and type of work (including distinctions for ‘light work’, ‘hazardous work’, etc.). To our knowledge, there are no publicly available cross-country estimates of the evolution of child labour, broken down simultaneously by gender, age and type of work.

This is unfortunate, since a set of time-series constructed from ‘contingency tables‘ cutting across age, gender and type of work would give us a much better picture of where to focus our efforts to fight child labour. Constructing such tables should be straightforward from the depurated micro-data used to produce the existing global reports.

Relatedly, it would be similarly helpful if the depurated cross-country series published in the World Bank – World Development Indicators were expanded to account for more flexible definitions of economic activity beyond “one hour of work in the reference week”.

Some exercises along these lines have already been undertaken in academia. As we discuss above, Schultz and Strauss (2008) present estimates of ‘children in economic activity’, by type of activity (market work and domestic work) and by number of hours worked. To do this, the authors used mainly UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) from 2000 and 2001. It would be extremely helpful for researchers and policymakers if such exercises were updated and published regularly in open-access data portals.

Regarding gaps in empirical research, it is important to highlight the lack of robust evidence speaking to the consequences of child labour on future outcomes – such as the working children’s subsequent health and earnings in adulthood. Schultz and Strauss (2008) provide a summary of available evidence on this research front. The body of literature is thin and the econometric results tend to be fragile because of difficulties to establish causality.

A related research question for which there is little robust empirical evidence is whether child labor is the result of ‘agency problems’ – namely, whether children work because parents fail to fully consider the tradeoffs and costs that work has on their children.

Children in employment (country-specific historical data)

- Data Source: Toniolo, Gianni, and Giovanni Vecchi. Italian Children at Work. 1881—1961. Giornale degli economisti e Annali di economia (2007): 401-427.

- Description of available measures: Share of children ages 10-14 (total, and by gender) who are economically active

- Time span: 1981-1961

- Geographical coverage: Italy

- Data Source: Cunningham, Hugh, and Pier Paolo Viazzo. Child Labour in Historical Perspective 1800-1985: Case Studies from Europe, Japan and Colombia. No. hisper96/1. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 1996.

- Description of available measures: Share of boys and girls (ages 10-14) recorded as working

- Time span: 1851-1911

- Geographical coverage: United Kingdom

Children in employment (consolidated cross-country data)

World Development Indicators published by the World Bank (based on data from ILO, UNICEF and the World Bank)

The main source of consolidated data on child labour is the inter-agency research cooperation programme Understanding Children’s Work. The principal source for this programme is the ILO’s Statistical Information and Monitoring Programme on Child Labour (SIMPOC), which is the statistical arm of the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). Understanding Children’s Work links the SIMPOC data with data produced by the World Bank (specifically the Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study datasets) and UNICEF (specifically datasets produced with the organization’s so-called Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys); as well as data from direct partnerships with national statistical offices. Details about the corresponding household surveys used to produce these datasets, including information about sample size, sample units and coverage, can be found in survey catalog of Understanding Children’s Work.

- Data Source: Understanding Children’s Work project based on data from ILO, UNICEF and the World Bank. This data is published by the World Bank.

- Description of available measures:

- Share of children aged 7-14 (total, and by gender) involved in economic activity for at least one hour in the reference week of the corresponding survey (irrespective of school attendance)

- Share of children aged 7-14 (total, and by gender) involved in economic activity for at least one hour in the reference week of the corresponding survey (not attending school)

- Share of children aged 7-14 (total, and by gender) involved in economic activity for at least one hour in the reference week of the corresponding survey (working while attending school)

- Time span: 1994-2015

- Geographical coverage: Global by country (predominantly low and middle income countries)

- Link: http://data.worldbank.org/indicators

The ILO Programme on Estimates and Projections of the Economically Active Population (EPEAP) has been producing statistics on labour force participation (for adults and children) since 1945, through the database known as ILOSTAT (formerly LABORSTA). Many studies rely on the LABORSTA/ILOSTAT data to shed light on the extent of child labour in the 20th century, before ILO started producing specialized child labour data. LABORSTA/ILOSTAT data is however problematic as a source to measure child labour, since data on work inside the household (even market work) are often not collected. Schultz and Strauss (2008) say that this source is not reliably useful for analyzing changes in child labor over time, given that the survey instruments, coverage, and estimation methodologies are not designed for this purpose.18

- Data Source: ILO Programme on Estimates and Projections of the Economically Active Population (EPEAP), through the

- Description of available measures: Labour force participation rates by age groups

- Time span: Since 1950

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Link: http://www.ilo.org/ilostat/

Children’s time allocation (cross-country data)

The UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, which can be obtained upon request, contain rich information about children’s time allocation in 108 countries (essentially the same set of countries for which the World Bank publishes the data referenced above). They include a child labour module which asks children 5–14 whether they work outside of their household in the last week and the last year as well as how many hours they worked outside the household in the last week. The surveys also collect hours in the last week for work in domestic chores and in the household business.

- Data Source: UNICEF MICS

- Description of available measures: Children’s time allocation outside their household and in domestic chores in the household

- Time span: 1994-2015

- Geographical coverage: Global by country (predominantly low and middle income countries)

- Link: http://mics.unicef.org/

Composite indices

Maplecroft’s Child Labour Index evaluates the frequency and severity of reported child labour incidents in 197 countries. The private risk analysis firm producing the data does not provide details about its methodology, but it does produce periodic analysis reports that are publicly available. Further information can be found on Maplecroft’s website.